The data on the number of foreign minors who arrived in Italy by sea in 2016, released at the beginning of January by the Ministry of the Interior and thereafter taken up by NGOs and various associations, caused more than one voice to be raised. For Massimiliano Fedriga, head of the Northern League in the House, a large part of the “almost 26,000 fake foreign minors who arrived in Italy in 2016 are not, in reality, children but adults passing themselves off as minors.” A position that has been expressed before by Northern League leaders and one that Fedriga and his colleagues justify with the following statistic: “only 7.5% are younger than 14, while 81% are between 16 and 18 years old.” It would be easy for an eighteen year old to claim that they were younger in order to “enjoy protections reserved for minors”. That same data, and the great amount (perhaps too great) not yet collected, however, tell a different story.

Underestimated numbers and uncertainties about age

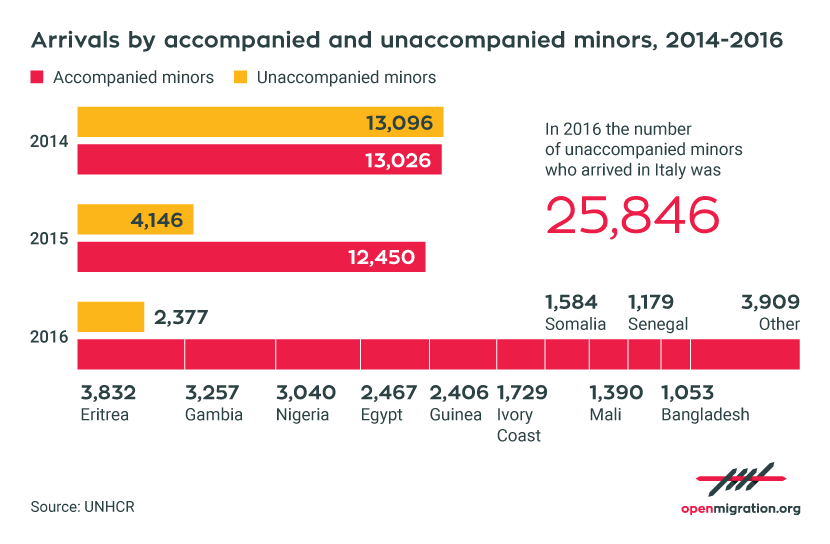

According to the Viminale, 25,846 unaccompanied foreign minors arrived in Italy last year. A “record” number that is two times larger than the one the year before. However, the number of minors registered in reception centres or with private foster parents was only 17,245 according to the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs. Here too we are confronted with the highest number we have ever seen: at the end of 2015 there were more than 11,000 unaccompanied foreign minors, which was already higher than the 5,942 recorded in January 2014.

Up until this point, however, the figures don’t add up, or rather, they aren’t enough. For Erminia Rizzi, a lawyer with Asgi, the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration, they “do not explain the phenomenon at all because the numbers are underestimated and hide the complexity of an explosive situation.” Those who have not been counted, Rizzi adds, are first of all “those minors who have entered through Austria and Slovenia, who have hidden themselves on ships across the Adriatic or who have arrived by air.”

Numbers which are not effectively available, as Maria Caprara, head of the Interior Ministry’s department for the reception of unaccompanied minors and who spoke before a parliamentary commission of inquiry at the beginning of January on Cie’s, Cara and reception centres, has said. But not insignificant: after Egypt (2,801) and Gambia (2,252), Albania is the third largest nationality represented at 1,573 persons.

Albanians and with them Afghanis, Bengalis, Pakistanis and Kosovans, which account for 20% of those received and arrive in Italy above all via land routes, in any event, were not included in those “almost 26,000” minors in 2016. Furthermore, Rizzi stresses, this has not taken into account “all of those people who have mistakenly been declared to be adults upon landing.” The attribution of age is, in fact, one of the most critical aspects of the Italian system. So much so that the law which was proposed – elaborated in 2014 together with Save the Children and currently held up in the Senate – would start precisely here.

“The new law,” Fosca Nomis, head of advocacy for Save the Children Italy, explains, “will make the current, fragmented system, which has led to differing practices as regards establishing age, reception and familial custody, more transparent.” In cases of uncertainty, “age will be judged at first reception centres in a tighter manner and with cultural mediators present.” In spite of laws and sentences “according to which, in the case of doubt, a younger age is to be given,” Erminia Rizzi adds, “the so-called taking of the pulse through radiography, which has by now been scientifically declared inadequate, is still common, a practice which must be replaced with multidisciplinary exams”.

Carla Trommino, an authority on children’s rights for the province of Syracuse, says that “it is not uncommon for boys, even those who have IDs with photographs listing their age, to be declared adults after they arrive.” For Rizzi the paradox is that “the police forces are suspicious of people declaring themselves to be minors, and are thus predisposed to scrutinising or assuming someone is older by default, but they don’t do the same thing for the many minors who, though they are indeed younger, claim to be 18 because then they can claim they are traffickers or exploiters.” In other words, not “fake minors” as maintained by the Northern League, but rather fake adults, easier to blackmail because they are less protected, at least on paper.

Fleeing structures, too many “missing minors”

If establishing how many unaccompanied foreign minors have entered Italy is extremely complicated, it is far easier, and far more troubling, to read the data on “missing minors”. According to data from the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs, 6,508 minors were reported to the prefectures as having left reception centres in the first 11 months of 2016. Among the most represented nationalities are Egyptians, Eritreans and Somalis. The Egyptians, Fosca Nomis explains, “are often very young and experience extreme pressure from their families to send money home, often ending up in the hands of criminal networks that exploit them in terms of work, in terms of sex or in terms of other illicit activities.”

Eritreans and Somalis, on the other hand, are in contact with passeurs and, she continues, “must pay them to reach other countries where they have familial or friendly networks.” For Eritreans, first among nationalities of those minors who have arrived in Italy at 3,714 persons (data from the ISMU Foundation), in particular, “one could reduce the number of people fleeing those structures by actually relocating them to other EU countries.” Close to 4,000 young people, the majority of them Eritrean but some also Syrian, could be inserted into a programme for minors which, although having poor results for adults, never even got started.

“The Viminale says that they will pass it soon,” lawyer Anna Brambilla, member of Asi, says. “But it is obvious that, after months of waiting around with no news whatsoever, many return to the hands of traffickers in order to reach the borders up north.” Only in Rome, in structure A28, which is run by the NGO Intersos, can they find temporary hospitality. “We are working at the limits of legality,” Valentina Murino, the head of the centre, says ironically. “However, we are responding to a need and since 2011 have welcomed 3,500 minors, earlier mostly Afghanis and today mostly Eritreans, boys between the ages of 15 and 16 who stay, on average, 4-5 days before continuing northward.”

And it is there, just before the border of the Alps, in a wearying and too often lethal game of hide and seek many of them come aground. In the near future Intersos, together with Unicef, will open a mobile information counter because – in the words of spokesman Alessandro Verona – “the minors who are arriving here don’t have any legal information on their rights, and this exposes them to more risks, as the story of 17-year old Milet Tesfamariam, killed by a truck last October along the motorway tunnel, tragically shows us.” And if today the numbers are low, “in 2-3 months it will be a lot more difficult.”

An Eritrean himself, Abeil Temegen is another victim of the borders. “His story,” Anna Brambilla says, “illustrates the chain of omissions unaccompanied minors often encounter: encouraged to get away from the makeshift camps for adults in Messina, they claim to be 16 and then 21, make it to Rome, then to the hub of Milan, get stopped by police in Bolzano and then killed by a train just outside the capital of Alto Adige and, in the end, verified as minors by death.” The Brenner route, like the province of Como, the Tarvisio and Bardonecchia are becoming the hot spots for fleeing minors.

Reception, a system that is stuck

Flight also calls into question the second weak link of the “minors system” encountered after one’s age has been ascertained, that is: reception. For Carla Trommino, active in the province which witnessed the highest number of arrivals in 2016, thanks to the port of Augusta “the current interaction between the centres managed by the prefectures as exceptions, first reception centres, centres for adults used for minors or in mixed use with adults, create profound uncertainties in the young boys who are received.”

The procedure envisioned by the State-Regional Conference in 2014 would foresee, after identification, transfer to a first reception centre in which minors would begin to receive protection and a legal tutor and – after a maximum of 60 days – land in centres managed by the Sprar where they would be put into educational paths and helped in the process of integration, and possibly even given over to the eventual custody of a family. Nevertheless, at present there are only 2,039 spaces available with the Sprar and the objective of reaching 4,000 seems a distant dream, especially when considering the inadequate response of local institutions to the most recent tenders.

A bottleneck which drains into first reception centres and very first reception centres, opened last summer in those regions most affected by disembarkation, and often ignoring regional regulations. Centres in which people end up staying until they are 18. And yet, according to Erminia Rizzi, by now “detention in those hot spots where minors who have just arrived stay isolated for months” has become the norm. Up to three in that of Taranto, according to the lawyer, 40 days in that of Pozzallo and seven at the maximum in the makeshift camp at the port of Augusta.

The “big box” reception centre for foreign unaccompanied minors in Reggio Calabria. The services inside the gym (2 toilets and 3 showers) are not enough for the one hundred UAMs who live there. Photo: Arianna Pagani.

“It is often a hostile first reception, in isolated structures with unprepared workers,” Gandolfa Cascio, a psychologist and coordinator of Terres des Hommes’ operations for the provinces of Catania and Syracuse, says, “and risks re-traumatising the minor.” The indefinite wait and an incomprehensible bureaucracy “create a limbo that repeats and amplifies the echo of traumas they experienced in Libya. In Sicily, just like in the Libyan jails, they remain suspended by a ‘maybe tomorrow’ – there it was the trafficker’s promise of freedom and here it is the appointment at police headquarters or transfer to a more well-equipped centre; in the middle of it all, dead time.”

They flee, in other words, to continue their journeys, but also because of desperation. In a Sicily that, on its own, last August hosted more than 40 per cent of all unaccompanied minors in the whole peninsula (data from the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs), there are those who are trying to create honest chains. Among them is Mediterranean Hope’s “Case delle Culture”, a project by the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy that can host up to 50 minors in the historic city centre of Scicli in the district of Barocco.

“We do something that may appear banal,” Valeria Ponente, coordinator of educative activities, says. “We go through all the bureaucratic steps together with these minors, and work together with institutions and associations to create a chain of structures with adequate standards, even for those who are older than 18.” Since its opening, the Casa delle Culture has hosted 606 persons, 179 alone in 2016. All minors sent from the hot spot of Pozzallo, just a little bit away, “and helped, whenever possible, to be legally reunited with family members in other European countries through long and exhausting processes.” This way you can also avoid flight and dramatic outcomes. “That stated, the huge reception machine, however,” Ponente emphasizes, “is stuck.” Without any resources, free spaces or controls, it is at risk of collapsing under the weight.

Translation by Alexander Booth.

Header photo: European Commission DG ECHO (CC BY-SA 2.0).