Fleeing compulsory military service and one of the worst dictatorships in the world, Eritreans cross the Mediterranean and arrive in Italy. Surprisingly, though, none of them wants to stay

In 2015, Eritrea had the record for sea arrivals of migrants and refugees in Italy. UNHCR estimates there were about 40.000, roughly the same number as 2014.

Why are Eritreans fleeing their country even in the absence of war?

Because this tiny country in the Horn of Africa fits the textbook definition of a dictatorship perfectly. The 2015 Freedom House report on Freedom in the World has included Eritrea in its list of the 12 “Worst of the Worst” countries (along with Saudi Arabia and North Korea, among others), the ones with the lowest possible rating for both political rights and civil liberties.

The current Eritrean President has been in office for 22 years (Isaias Afewerki came to power in 1993); there is no free press (the last privately owned media outlets were suspended and their journalists jailed in 2001 exit visas to leave the country are impossible to obtain legally, and with 17 behind bars, Eritrea remains the worst jailer of journalists in sub-Saharan Africa. Internet is practically non-existent: only 1 percent of the population goes online, and all Internet connections provided by EriTel, the sole state-run telecommunications company, must use the government-controlled gateway.

Following the events at Rome’s Baobab reception centre, the Eritrean case (link in Italian) has made the news again, even though it is largely neglected by Italian media.

Below we have collected five meaningful facts that describe the journey and the reasons for the exile of a people that does not enjoy good press and is struggling to find a home in Europe.

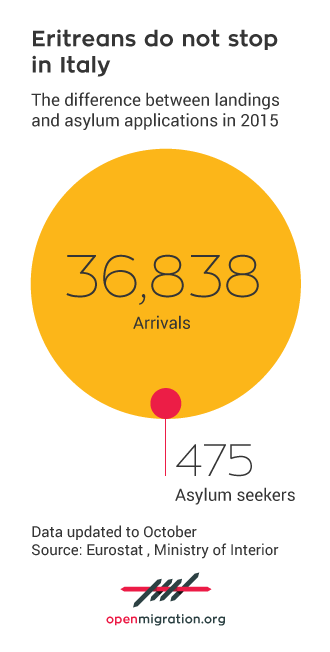

1. Eritreans: record arrivals in Italy, exceptionally few asylum requests

One very striking fact – partly explained by the Dublin Regulation – is the disproportion between arrivals and requests for asylum in our country. According to reliable sources, between 4000 and 5000 Eritreans flee their homes every month to reach seek refuge in Europe.

One very striking fact – partly explained by the Dublin Regulation – is the disproportion between arrivals and requests for asylum in our country. According to reliable sources, between 4000 and 5000 Eritreans flee their homes every month to reach seek refuge in Europe.

Nearly one out of a hundred Eritreans applies for asylum upon arrival in Italy.

2. When Eritrea was a colony

The history of Eritrean migrations to Italy is not a recent one. The first wave dates back to the early sixties, when the ties with our country were still rooted in the nation’s colonial past. Subsequent wars with Ethiopia – the one that culminated in the independence of Eritrea in 1991 and a further armed conflict in 1998 (with a death toll of 100.000) – have created a stream of refugees in addition to economic migrants. A pre-Afewerki and a post-Afewerki exodus, the former characterized by political clashes, the latter a post-ideological one, with young Eritreans trying to break free from the shackles of compulsory, indefinite conscription.

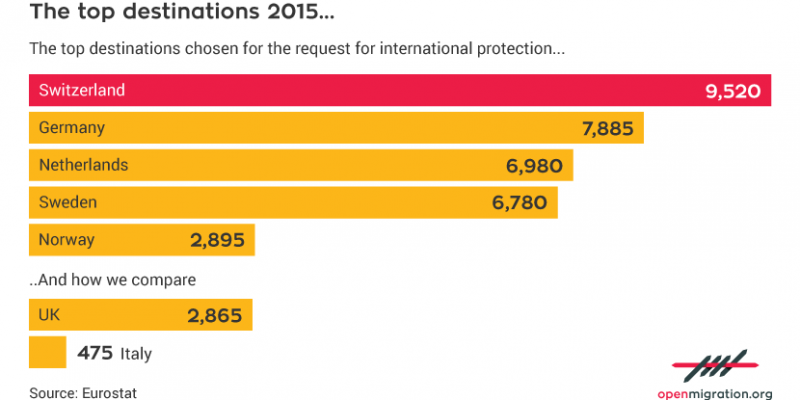

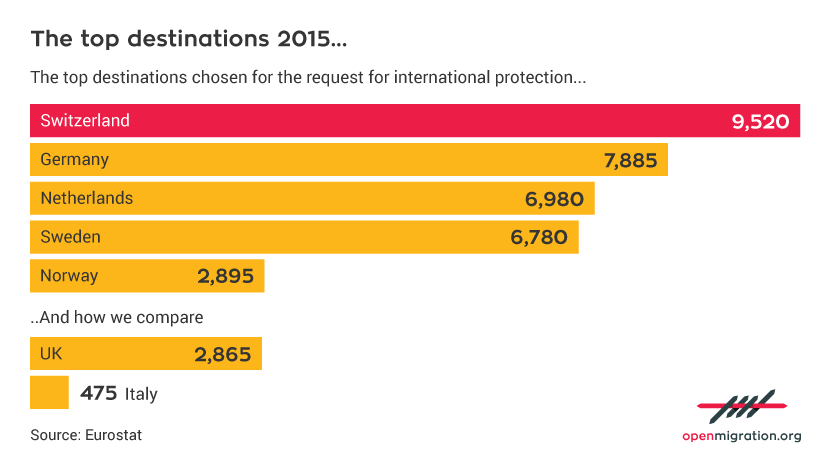

3. 30.000 requests for asylum in Europe

While Italy is only a country of transit for the new Eritrean migrants, their actual destinations, looking at the number of applications lodged – are Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and especially Switzerland, where international protection has been sought by 9.520 Eritrean citizens as of October 31st. In 2014, most Eritreans sought asylum in Germany (13.255 requests, accounting for 36 percent of all the applications lodged in the EU).

4. Escaping conscription

Most young Eritreans crossing the Mediterranean are fleeing national service, established in 1995 and recently extended to 18 months. However, according to Amnesty International, «conscription continues to be indefinite for a high proportion of conscripts. There is no provision for conscientious objection to provide an alternative civilian service for those who object to military service on religious, ethical or other conscientious grounds». Nearly 27.000 Eritreans between the age of 18 and 34 have sought asylum in Europe in 2015. In a lengthy report from Asmara, the Guardian has tried to shed light on the “mystery” of the exodus of young Eritreans.

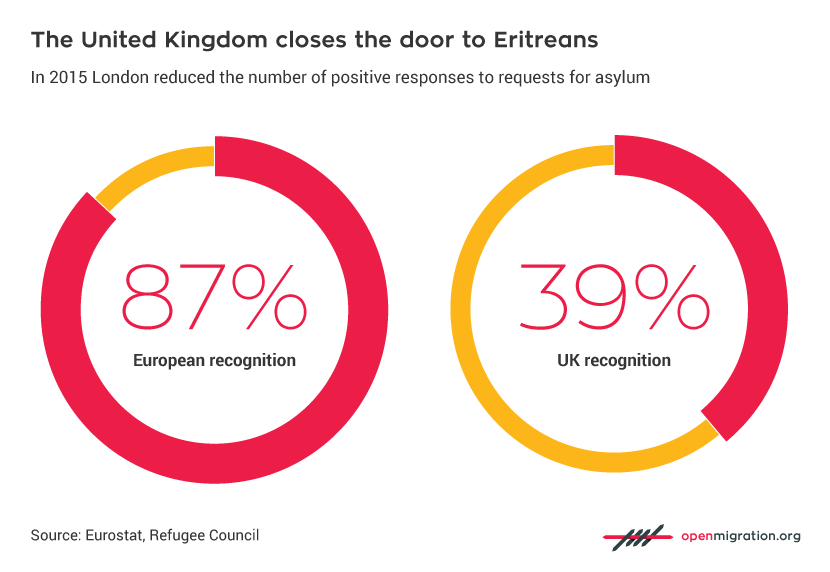

5. London and Copenhagen dismiss refugee claims

About a year ago, Denmark, followed by the UK, expressed their belief that the human rights situation in Eritrea had improved, and that there were fewer the reasons for fleeing the country (such as indefinite conscription). Therefore, both countries have begun to greatly reduce their recognition rates to Eritrean refugees, compared to the average rate in the EU.

Twitter: @alessandrolanni