In Part 1 you can find the history of the hub since 2013; in Part 2 you can read some of the stories of its residents. This is Part 3.

The warehouse of the hub on Via Sammartini was once a nightclub, the Shanghai Cafè, “a stylish all-night bar with a live band and modern Mediterranean cuisine.” There is no trace of the old club, no sign or furniture, and the large pool table is gone too. The warehouse has reverted to its old state, a railway cave, except for a staircase with an iron balustrade and a loft where the piano once was. Boxes are now piled up there as high as the ceiling. Anna, the warehouse manager, has a desk covered with papers next to the unloading bay. Many of those who come to bring donations wish to visit the warehouses. “Coming here,” says Anna, “means a lot to these people, they don’t want to just leave what they brought and be off. They want to see what it’s like, how it works.” At the old hub on Via Tonale, the volunteers had told me how donations used to come all the time, non-stop, and, in classic Milanese style, for the most part anonymously. “I would get there and find… boxes upon boxes of socks! How did the people know we needed socks?” Gianluca, a volunteer who is now part of the staff, had asked.

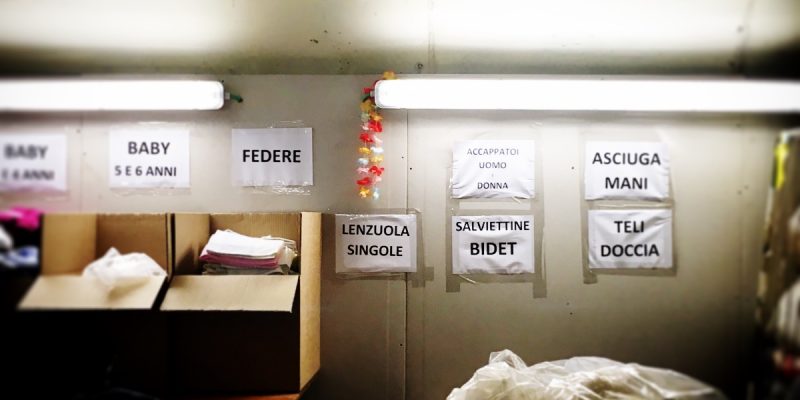

Anna takes me on a tour of the two depots connected by an archway, through a maze of shower gel bottles and towels, old camp beds waiting to be taken away, boxes with children’s clothes. The city regularly asks for donations; sometimes they are generic, sometimes more specific: diapers, tampons, wet wipes. Citizens always respond enthusiastically. The size of this warehouse – and you want to imagine more like this one, from Greece all the way to Germany – reflects the scale of the refugee emergency. It is touching that the people of Milan are keeping it well-stocked, but it’s hard to believe that, indeed, it always needs restocking.

Anna. PH: Marina Petrillo.

For three years, exhausted migrants at the hub have sought help from Doctor Mohamed Boustani. A short, bespectacled Syrian wearing a grey suit and a benevolent smile, his story seems like destiny: 66 years old, he has lived in Italy for almost 40 of them. One of eight children of a landowner, as a boy he saw his father welcome dozens of Italian archaeologists into his home, and dreamt of going to medical school in Italy. Even today, he calls the people in Parma who first took him in all those years ago “family”. A pneumologist and a surgeon, he got his degree in Milan. “I thank God a thousand times for sending this job my way, because these people are in so much need.” Today it’s raining, and all the young migrants who would usually be out playing soccer are sitting inside. Here, on the white plastic chairs under the neon lights, it feels very strange listening to the doctor tell us about the old Venetian neighbourhood in Damascus, or his own Mesopotamia, “the cradle of humanity, the land where wheat was first grown.”

“Ours is already a noble profession, we can never be indifferent,” he observes, “but working here, with these people, is incredibly rewarding. When they arrive they can barely walk, can barely eat. When the strain from the journey is over, they just collapse. Here, I can get them back on their feet with just some salts and some paracetamol: it’s the best job in the world.” Boustani started helping back in 2013, when the hub was still on the mezzanine floor of Central Station. “I got a call, they needed water and medicine, and someone who could speak Arabic. I used to go with my friends in the evening or at the weekend when I wasn’t on call. Sometimes I’d get a phone call at night. One day I brought along one of my sons to help us with the translations: there was a man whose feet were severely swollen because of an infection. He needed some antifungal cream, Councillor Majorino came to the pharmacy with me and my son.” I sense a thread in Dr Boustani’s tale: the link between helping and having been helped, his gratitude towards those doctors who gave him the opportunity to make this his day job.

Dr. Mohamed Boustani. PH: Marina Petrillo

The treatment that the travellers need reflect the plight of the migrant. Scabies is the most common ailment, a consequence of crossing deserts and seas. It is easy to treat, and no longer contagious after a few days. Dr Boustani tells me that the most frequent conditions are dehydration, malnutrition and chronic fatigue. “As soon as they get some rest, food and water, they regain their strength. You can see it right away, because they start smiling again. When they come here, they are skeletal. Usually they gain back about 1 kilogram a day, but there was once a girl who weighed only 35 kilos but who gained back 15 in five days. It was astonishing. The shocking thing, to me, is that sometimes they’re not starved from the journey; rather, they were already starving beforehand – it was hunger that drove them to travel in the first place.”

I ask him if he doesn’t need to know a patient’s history to make a diagnosis. Given the context of migration, it is as if all migrants shared one great medical history. “I can see what’s wrong with them at a glance – if they come in saying they have an itch, I know it’s scabies; otherwise I try to make them explain, we get by even when the Tigrinya translator is not on hand. Usually they don’t come with any lasting damage. The only lasting traumas are with those who were victims of sexual violence.” Then there are the burns, “because the boats are so packed, there’s no room, and someone gets too close to the engines, which are old and leaking fuel. Burns must be treated with antibiotics and hyaluronic acid ointment.” Some have been scarred by violence and war, too: “They may have gunshot wounds, bullet wounds; these injuries were often sustained in Libya. Syrians sometimes have abscesses from untreated shrapnel wounds. Others were treated upon arrival in the South of Italy.”

When I see Dr Boustani again, it is on a very cold day in late November, and the hub is full of new arrivals. He had gone out on the streets in a sweater and surgical gloves, and he is just returning to his practice. It’s a busy day. “So many children arrived today!” he says. And here they are, everywhere I look, kids sitting on the tables, one or two year olds, surrounded by grownups and city volunteers. Boustani told me he had witnessed dramatic psychological changes in the migrants over the last few months: “Now that they’re not just passing through for a few days, they grow restless, especially the younger ones; they stay up late chatting on their camp beds, and then they hang around during the day, they get headaches. They’re young and they need to keep busy, so I have to keep them in line if they try to skip. Before, they used to bounce back quickly, they were eager to resume travelling. They knew that the worst was behind them. But now they come here and they hear people talking about borders being closed, they know that they probably won’t reach their destinations.”

This is just what happened to Omar, a 38-year-old Eritrean from Baka Island, who fled his country in the attempt to reach Sweden but was forced to seek asylum in Italy where he disembarked three months ago. Omar used to speak Tigre at home, he understands Tigrinya, he is studying Italian and can speak perfect Arabic – the language from which Hani, an operator at the hub, is translating for us. Omar used to work in Saudi Arabia until he was caught working for someone who was not his sponsor. He was deported without papers and sent back to Eritrea. He had left to avoid mandatory conscription. One of his brothers, he tells me, “has been doing military service for 21 years.” Once back home, Omar only stayed for three weeks before attempting to flee again. “I went to Asmara and from there to Sudan, then Khartoum, then Alexandria, and from there I got on a boat some 100 kilometres away, in Rashid,” that is, the port of Rosetta. “Every time I crossed a border, I had to pay a smuggler. In Sudan I was stuck for a month while waiting for the smugglers.” He spent the last of his money on the boat ride (2,500 US dollars) and he had to pay 200 more upon arrival in Sicily. “The crossing takes eight days. They got eighty of us on a wood boat. After a day and a half, out at sea, they made us get on a slightly bigger boat: there were already 100 people on it. Then we got on a third boat, and by then there were 350 of us. There were women and children, too, maybe 50 kids, this tall, and ten babies.” I ask him whether they had food and water. “Water we had, and I had some candy and some cheese in my backpack. The smugglers gave us some loaves of bread, all mouldy; I was down in the hold for eight days.” That must have been hard. “Yes, but… tough africano!” he say, half in English half in Italian, with a big smile, patting his own shoulder. “Because there was drinking water in the hold, sometimes we would go up to bring the others a drink.”

Omar and his fellow travellers were rescued by a coast guard ship. “They came to find us about half a day after our call; we stayed on board for a day, then they dropped us off in Messina. Upon arrival, they took front and side shots of us, and at the reception centre we were forced to give our fingerprints. Many didn’t want to, because they didn’t want to stay in Italy, and I saw policemen beating them up. They broke a guy’s arm, and another had a split lip. I went to complain, because I speak some English. A policeman, when he realized we could communicate, said that the fingerprinting was only a formality. I told him I was going to Sweden, I didn’t want to stay here. But he insisted that it was just for identification purposes, that I need not worry, that it was not legally binding. So I gave him my fingerprints, and then it turns out it was.”

“On the same day, August 15, we left the reception centre. We slept at Messina railway station, then we took a bus to Rome, and from there to Milan. They dropped us off at Lampugnano” – on the other side of the city from the Sammartini hub, which was then unknown to Omar – “and from there we managed to take the metro, jumping over the turnstiles because we didn’t have tickets, and changing lines at Central Station. When I arrived, I called my brother in Sweden and told him about the fingerprints, and he said: ‘They screwed you over. You’ll have to stay in Italy now’.”

From a simple migrant passing through, Omar has become one of the many asylum seekers whose number has skyrocketed since the Dublin Regulation began to be enforced to the letter. He helps out at the hub with odd jobs and translations, and operators have helped him initiate asylum procedures. At least in his case it should be rather quick, unlike those who come from countries that are considered “safe”, such as Gambia or Senegal. Omar doesn’t want to go to another centre while waiting: he likes it here because there are different people every day. He has two sisters and seven brothers. When I ask him if he was afraid during his journey, he places a hand on his heart and says: “I’m never afraid.” Then, pointing to the sky, he adds: “I fear only God.”

Omar & Hani. PH: Marina Petrillo.

Before we part, he says he’s a supporter of the Roma soccer team, so I ask him if he ever plays with the others. “I can’t, I’ve got a bad knee.” “Tough africano, eh?” I quip, and he laughs. He has a bead bracelet, black and yellow, that survived the trip from Africa: “It’s a Bob Marley bracelet. It says ‘Iron, Lion, Zion’.”

Header photo: the hub’s warehouse. All photos by Marina Petrillo.