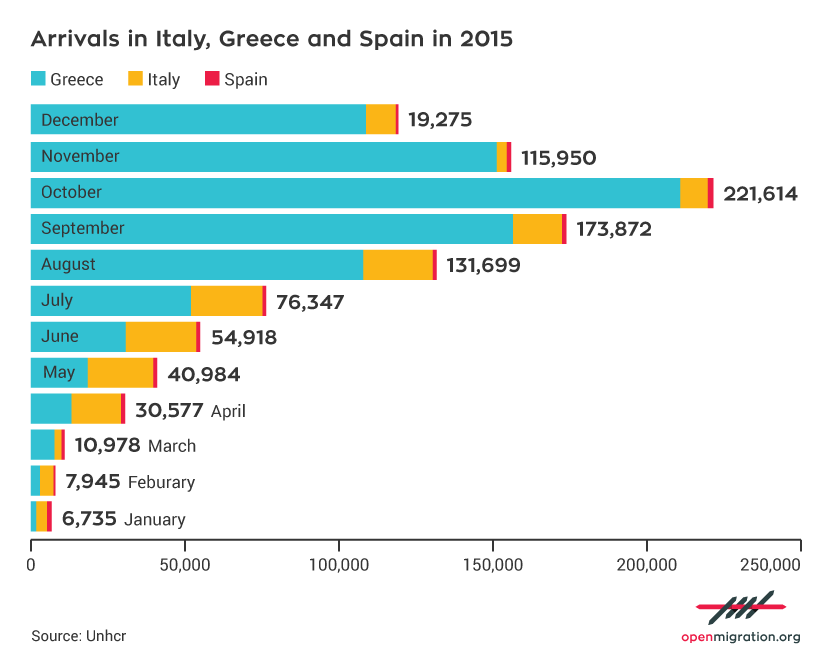

«A hundred migrants try to climb over the Melilla wall» (February 18). «Eleven migrants rescued after boat capsizes near Gibraltar Strait» (February 18). Spain seems like a forgotten frontier, far away from the tragedy of the refugee crisis of 2015 and early 2016. Of course, there are still news, yet one only needs to look at the number of refugees who arrived in Spain in 2015 to realize how dramatically the influx has shrunk.

1 million sea arrivals in Europe in 2015, only a few thousands in Spain. 1.3 million asylum applications lodged, only 13.000 in Madrid. How is it that the only European country adjoining Africa – with Ceuta and Melilla, the two Spanish enclaves in Morocco – has not been touched by the wave of refugees and migrants that hit Europe last year?

Coverage by the media has been scarce; their attention has been – understandably – turned elsewhere. Yet there still exists a small, steady influx of people trying to cross the Pillars of Hercules, fleeing Africa to reach the Iberian Peninsula. Better yet, there still resists, because over a period of ten years, the southwestern migratory route has been all but relinquished, and not by chance. The Syrian war has obviously upset all statistical indicators; however, the decline in the number of migrants headed to Spain has other reasons, besides the natural turnover in migratory routes. All of this in a country which certainly has a history of immigration from Latin America, but which has also been receiving a steady influx of African immigrants for the last 25 years, just like Italy. These now account for about 10 percent of the Spanish population (4.460.000 out of 46 million inhabitants), according to data from Ine.

The Canarian route

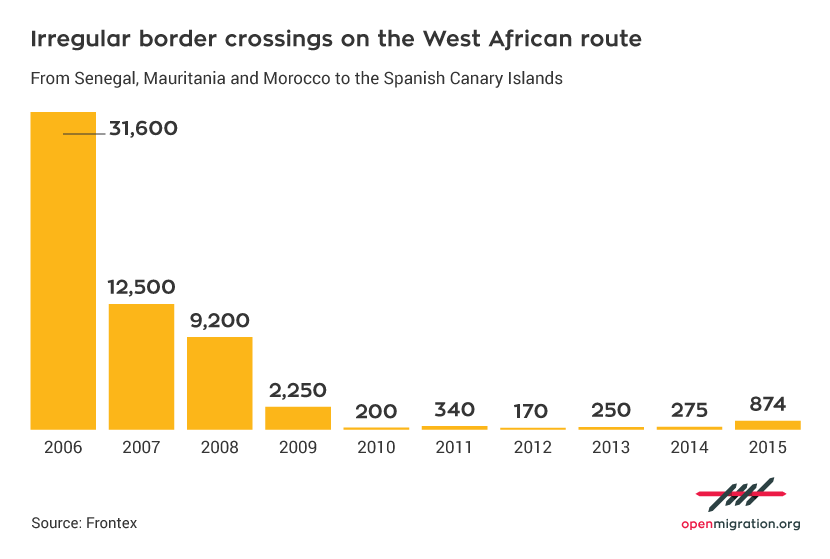

«Very good operational cooperation, between Spain, Senegal, Mauritania and Morocco has significantly reduced the pressure on the route towards the Canary Islands and south of Spain», reads the latest Frontex-AFIC joint report (December 2015). This cooperation, also called «border externalization», has begun to pay off in recent years: a reduced influx of irregular migrants, more repatriations for those who have managed to cross the continental border. The deal between Spain and Morocco has also been greenlighted by the European Commission.

Spain’s management of the southern frontiers is a political and technological laboratory for border surveillance. The SIVE (Sistema Integrado de Vigilancia Exterior) system has been in place since 2000: a complex control apparatus, constantly processing data received from boat radars operating in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, video feed from watch posts along the coast, satellite and aerial signals. A form of capillary monitoring that has turned Spain into an example for many.

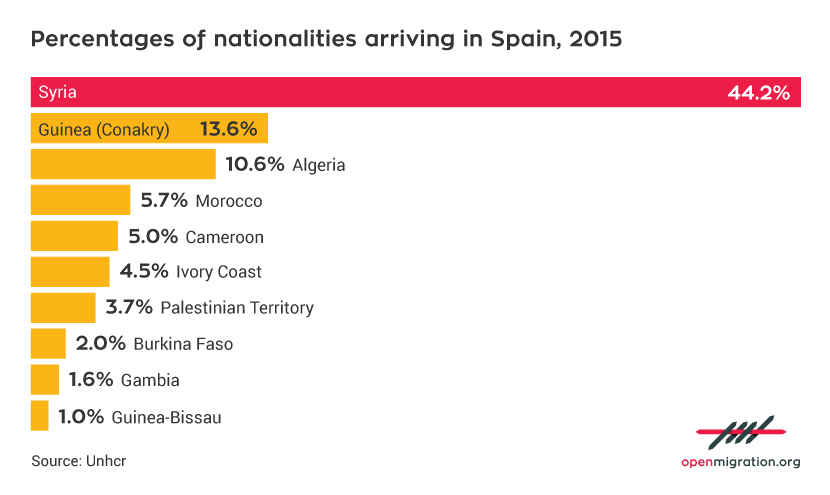

Only ten years ago, the Canary Islands were the main southern gateway to Europe, with more than 30.000 disembarking on the archipelago in 2006. Today, fluxes have changed and barely a few hundreds attempt escape via the western route. The crossing to Gran Canaria is too dangerous, the patrols too frequent, leading sub-Saharan migrants to head north instead, towards Ceuta and Melilla, or the northern shores of Morocco. According to Frontex data, fewer than 1.000 migrants have disembarked on Atlantic coasts in 2015: 315 from Guinea, 136 from Ivory Coast and 85 from Gambia.

Ceuta and Melilla

«These fences and moat, combined with implementation of readmission agreement between Morocco and Spain, reinforcement of Moroccan Border Guard Units protecting the fence and dismantlement of makeshift camps of irregular migrants, have reduced the numbers attempts». Again, the source is Frontex. The towns of Ceuta and Melilla are now heavily fortified and virtually impregnable. Surrounded by triple 10-meter fences and moats, ferociously protected by frontier guards, they have become the symbol of exclusion. It has been more than ten years since the tragic day when 11 migrants were killed by the frontier guards’ gunfire as they attempted to scale the fences, and the violence hasn’t abated. Many human rights organizations denounce the violation of migrants’ rights, when they are intercepted and turned away directly on Moroccan soil, without any legal protection.

In recent years, Mohammed VI’s Morocco has behaved very much like Gaddafi’s Libya, controlling migrant outflow as an instrument of political negotiation. Pressure on the EU and Spain is necessary? The assault to the borders at Ceuta and Melilla is facilitated. The deal works? Control and militarization of territories and waters are increased to intercept boats in the Atlantic and desperate people clinging to the fences at the borders.

According to Bez.es (quoting sources from Morocco’s Royal Gendarmerie), 18.000 sub-Saharan migrants attempted to climb over the fences marking the borders in 2014, and more than 12.000 were turned away at sea, with 75 percent coming from Senegal and Mali.

Today, there is an obvious decline in migration. According to data from the Guardia Civil (published in the December 2015 joint report “Ceuta et Melilla, centres de tri à ciel ouvert aux portes de l’Afrique”), in 2014 2,682 migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and 3.566 Syrians and Algerians arrived in Melilla only. By the end of May 2015, only 252 African migrants successfully crossed the borders, while the number of Syrians and Algerians had already reached that of late 2014: 3.525.

These figures differ from those provided by UNHCR, according to which the Syrians who entered Melilla (approximately 5.000 km away from Damascus) during the first half of 2015 were 4.049 (on a total of 4.849 arrivals), about twenty times the number of Syrians (252) who arrived in 2013.

Asylum requests

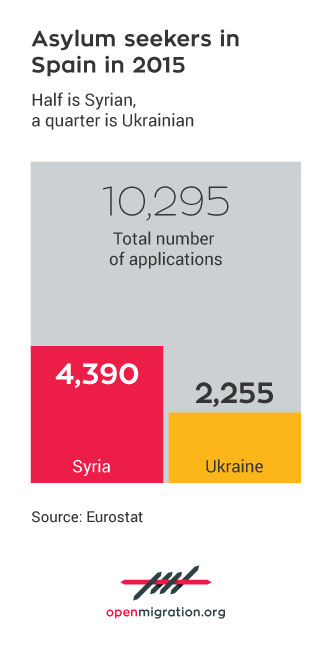

A recent Bez article reports that according to Cear (the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid) estimates, Spain has received 13.000 asylum applications in 2015 (official data as of late September), more than twice as many as in 2014, and a good number of those came from the Identification and Expulsion Centre in Melilla.

According to the latest available Eurostat data, there were 10.295 asylum applicants as of late September 2015, about half of whom (4.390) were Syrians. Asylum requests in Spain reached their peak in September, when 1.425 migrants lodged an application. By way of comparison, there were ten times as many requests (11.195) in Italy in the same month, which means that asylum seekers in Spain in 2015 were about a sixth of those in Italy.

It should be noted that the country with the second highest number of asylum seekers is the Ukraine, a country situated very far from Spain, like Syria. Very likely, a significant portion of the thousands of Ukrainians seeking refugee status did not arrive in 2015, but were already in Spain and opted to regularize their status through asylum after the conflicts escalated in Kiev.

Further proof that the immigration factor in Spain changed during the last season has come from the so-called refugee relocation programme. According to the plan devised by the EU last autumn to redistribute a quota of refugees throughout its 28 Member States, Spain was to receive about 15.000, from Italy and especially Greece. Receive, not send. Therefore, with the choices made over the last ten years, the Spanish government has distanced itself from its brother nations in the Mediterranean, from which asylum seekers arrive.

That only a few dozens of refugees have been sent to Spain, however, is an entirely different matter.

Twitter: @alessandrolanni