It was 6:40 in the morning when the crew aboard the rescue vessel Iuventa sighted the rubber boat. Aboard were 129 people from Gambia, Senegal, Ghana, Guinea, and Nigeria, among other countries. They had departed six hours prior from the coast of Libya, where they were brought by paid smugglers. Thanks to the rescue mission, conducted by the German NGO Jugend Rettet 20 nautical miles off the coast of Libya, all of them survived that day.

Among them was Malick Jeng, 19-year-old Gambian whose life I documented with my photos since he was rescued from the sea. He is one of the 362,753 refugees and migrants who reached Europe by crossing the Mediterranean in 2016. Malick left his hometown of Banjul, the capital of Gambia, five months before that rescue day in August 2016. He walked away alone, without telling his family, like many young people who have attempted the journey to Europe before him. After passing Senegal, he crossed the desert in Mali inside an oil tank, where he nearly suffocated. And once he arrived in Libya, he was imprisoned for a month.

Malick lies on his bed in Hotel Colibri, in the city of Biella, where he lives since August 2016. He shares room with three more people from Gambia and Senegal. (Photo: César Dezfuli)

Denounced by the International Organization for Migrations as a “slave market,” Libya, plunged into a power struggle since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, is home to various armed groups that prey on sub-Saharan migrants in order to make money. They manage the migratory routes to the coasts, as well as the prisons where migrants are often confined and abused, their families extorted to pay for their release.

Inside the prison in Libya, Malick had to witness the murder of some of his fellow travellers. And as soon as he was released, thanks to a payment sent by his family, he immediately got in touch with a smuggler who transferred him to a “connection centre” in the Libyan capital city of Tripoli. He waited there for weeks to be taken to the beach and depart towards Europe.

Entrance of Hotel Colibri, the closed hotel-turned-temporary reception centre in Biella where Malick lives. (Photo: César Dezfuli)

After the rescue, Jeng was first transferred to Sicily and then to Biella, north of Italy, where he has lived ever since, in a temporary reception centre called Hotel Colibri – an old hotel that had been closed for 10 years. The hotel was turned into a temporary reception centre for asylum seekers in August 2016, with capability for up to 55 people. All the current residents are from countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and are housed in rooms that can accommodate between two and four people. Cooperatives and private companies are running asylum centres such as this across Italy. All migrants receive Italian classes twice a week, in which they learn basic conversational skills to get on in their daily lives, as well as how to prepare their CV. At Hotel Colibrì, Malick shares a room with three more people from Gambia and Senegal. He seeks political asylum in Italy and, as an asylum seeker, he has the right to stay in this centre as long as his asylum process lasts, which usually takes a maximum of two years.

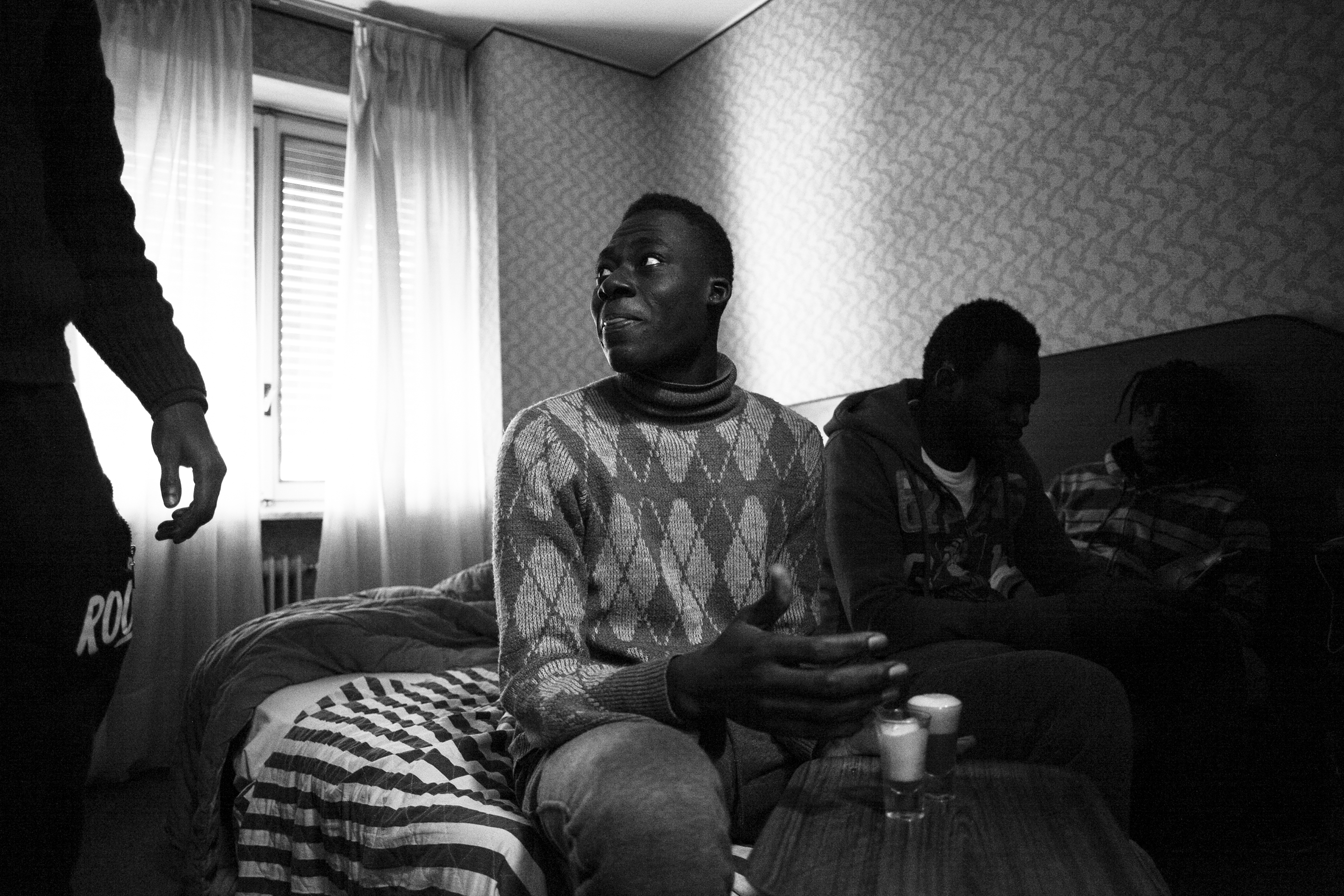

Malick prepares tea in the room of his friends, using a small electric heater. He follows the ritual of preparation of the tea that used to perform when he was next to his family. Once the tea is ready, he offers it to his friends while he continues preparing more. This is a way to consume part of his time in the temporary host center. (Photo: César Dezfuli)

However, he knows that his chances to obtain the refugee status have been recently limited due to the political changes in his country. Malick left Gambia, like many of his countrymen, because he was tired of the lack of freedom, the political persecution, the corruption and the uncertain future due to the dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh, who had been in power since 1994. However, Jammeh was removed from the government in January this year, after losing the election to Adama Barrow, who is now in power, and who has promised to start a new era for the West-African country.

Malick, along with his colleagues from Hotel Colibri as well as from other migrant centers in Biella, attending Italian classes. All migrants receive Italian classes twice a week, in which they learn basic conversational skills to get on in their daily lives, as well as how to prepare their CV. (Photo: César Dezfuli)

Malick celebrates the changes in his country, but he doesn´t trust things will change so easily there. And, after all the risks he has gone through on his way to Europe, he wants to have the opportunity to start a life away from a country that one day decided to escape and to which, for now, he does not want to return, since its stability is still in question.

For now, he remains awaiting a response to his asylum application to find out if he can begin a life in Europe legally, as a refugee, or whether he will be forced to keep struggling for his future.

Cover photo: Malick, from Gambia, looks at the sea from the rescue vessel Iuventa, seven hours after departing from Libya in a rubber boat with 120 others. Photo by César Dezfuli, like all photos in this article.