In collaboration with:

![]()

Let us consider two passages from a recent UNHCR report (December 2015, the data refers to the early months of the year) on the press coverage of the refugee and migrant crisis in Europe.

The first:

Press coverage [on immigration] was very much an outlier. Its coverage was far more polarised than anything we find in the rest of this EU sample. This meant it is impossible to talk about XY coverage in general terms, but instead it is necessary to talk about individual newspapers.

The second

The YX press featured the perspectives of migrants and NGOs prominently which allowed significant space for sympathetic stories about the plight of migrants and refugees, as well as advocacy on their behalf.

The former describes the polarization, the impossibility to synthetize the variety of styles employed to narrate the refugee crisis. The tone ranges from alarmed to reassuring, the stance is alternatively for and against; some articles try to understand the reasons, to describe a phenomenon, others want to stir up controversy. The latter describes a relative homogeneity among the voices in the press, mostly in agreement with a common basic proposition. We have deliberately omitted the nationalities of the press cited by the UNHCR.

These are, in a nutshell, the different types of Western journalism, as described by Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini in their book Modelli di giornalismo. The Mediterranean model, which includes Italy and Spain, is fragmented, polarized; it is pluralistic, but in the sense that each individual media outlet represents a certain segment of the public opinion.

Contrariwise, in the Anglo-Saxon model, the cultural and ideological poles are not represented by the various outlets, but can coexist in the same news desk. Hallin and Mancini have dubbed this “internal pluralism”, as opposes to the external polarization which is found in the Italian press.

Polarization in the UK

At this point, it seems straightforward enough that the first passage refers to Italy and the second one refers to the UK. It is, in fact, the opposite. Surprise: 2015 was the year when the British press found itself divided over the refugee crisis, while the Italian press displayed a tendency to homogeneity, at least, and a relative placidity.

Let us take a look at the data.

On one hand, in closely following the refugee crisis, there is the Guardian. On the other hand, the right-wing and conservative press have supported (and continue to support) a hard line against refugees and migrants.

As the Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies remarked, this polarization emerges by observing the low proportion of articles which featured humanitarian themes (20.9% in the Daily Mail, 7.1% in The Sun, while the EU average is 38.3%), as well as the high ratio of articles which emphasized the threat that refugees and migrants pose to Britain’s welfare and benefits systems (Daily Telegraph 15.8%, Daily Mail 41.9%, Sun 26.2%, EU average 8.9%). The Guardian on one side, and tabloids (but not only them) on the other.

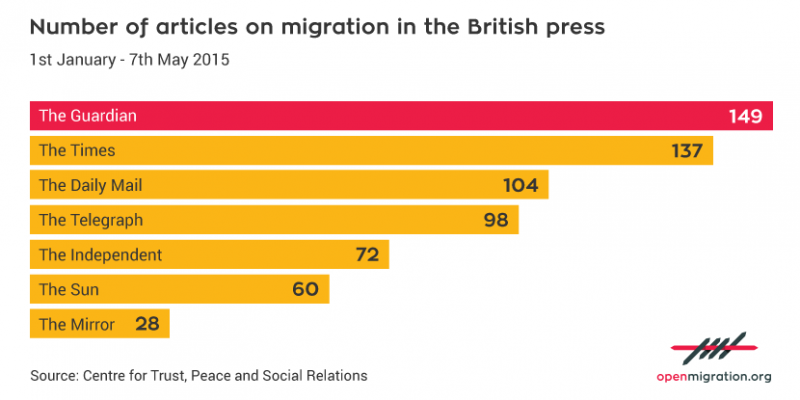

In the UK, higher concerns over the arrival of new migrants are mirrored by the way in which the newspapers treat the issue of immigration. According to the data collected by the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations in the study “Victims and Villains. Migrant Voices in the British media”, nearly half (46%) of all the articles framed migration as a threat and migrants as actual of potential “villains”.

What is the cause of this largely new attitude? «In many media», observes Nando Sigona, a professor with the Institute for Research into Superdiversity at the University of Birmingham, «the refugee crisis and the issue of immigration are a means, not the end. The end at this stage is the exit of Great Britain from the EU, the so-called “Brexit”, and the creation of the “danger of invasion” is instrumental to the agenda». Furthermore, it must be remembered that in May 2015 the UK had a general election: all political communication needed to break through to voters, playing with their fears and magnifying them.

The Italian “normalization”

«The most homogenous press systems were those of Spain, Italy and Sweden. Newspapers within these countries tended to use the same language, report on the same themes and feature the same explanations and responses.» In Italy, reads the UNHCR report, there was a common voice narrating the crisis, at least in the early months of 2015.

The UNHCR calls it “homogeneity”, Nando Sigona dubs it “normalization”. «Coverage of the crisis in Italy has become more cautious and better informed, in part by appropriating the strategy of “normalization” pursued by the government. The risk is that coverage becomes too subservient to the official narrative. The situation out in the field is changing rapidly and the press needs to step up as a watchdog.»

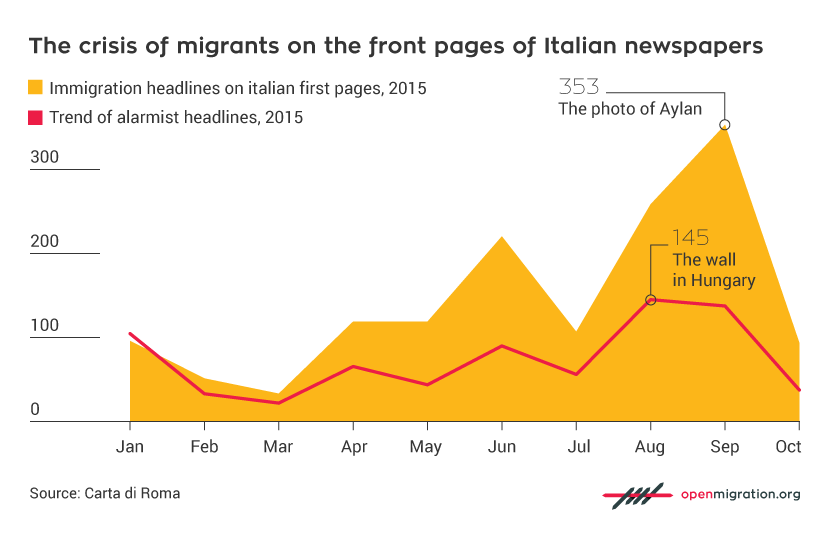

Over the course of the year, fear-mongering headlines on immigration have remained a consistently small portion of the media coverage. Even though immigration has been equated with terrorism, «reception is the theme around which most stories on immigration revolve: more than half of the headlines (55%) contain a reference to the management of incoming migrants and refugees», says the Carta di Roma report “Notizie di confine”.

The distribution of alarmed and reassuring headlines has been mostly balanced – with the exception of Il Giornale, where only 9.2% of the articles has a non-aggressive tone.

A certain amount of diffidence persists towards the other, towards “the world”, as Ilvo Diamanti called it in his preface to the 9th Report on security and social insecurity in Italy and Europe, conducted by Demos & Pi and Osservatorio di Pavia on behalf of Fondazione Unipolis. However, the foreign “other” does not frighten as an immigrant: as of January 2016, only 6% of Italians considered immigration an emergency; 21.4% in Great Britain and 43.7% in Germany.

The other frightens rather as a potential terrorist, criminal or job-stealing intruder. And this is what the anti-immigration propaganda has been doing: using foreigners as a catalyst of all the fears that course through society.

Having said this about the Italian newspapers – in a country where, according to Censis, 96.7% of the population says that they watch TV and 76.5% says they keep up to date on current events watching news programmes – the correlation between fear and TV information is a crucial one. How much are we affected by the sight of the lifeless body of a little boy on a beach in Turkey? And how much by the news of a foreign citizen committing murder?

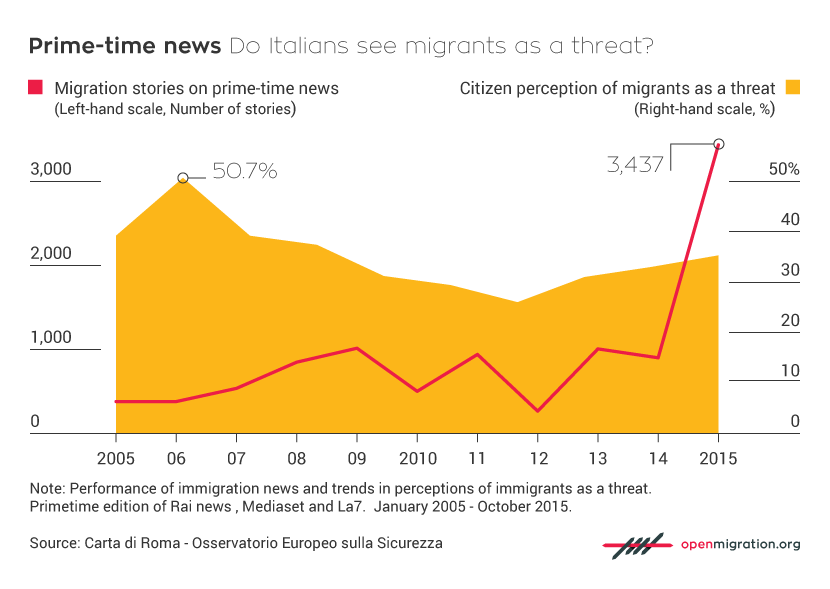

Let’s see what the figures say. In 2015, 3.437 features on immigration and the refugee crisis were aired by primetime news programmes of Rai, Mediaset and La7, 1996 of which were aired in the first half of the year, and 1441 in the second half. It is a record number for Italy, and more than three times as many as the ones aired in 2014.

However, as the third report “Notizie di confine”, published by Carta di Roma, cautions – and as shown by the chart above – «there is no correlation between the number of news items and the increase in fear of migrants».

Was 2015, then, the year when the Italian media developed a more mature attitude towards immigration? Giovanni Bellu, president of Carta di Roma, is not convinced: «let us consider that many changes in the media discourse occur during election campaigns. It would be difficult to describe this an overall structural change». With the impending elections in June, 2016 will be an important test that will decide whether the “normalization” of Italian print and TV outlets is a solid reality, or just a momentary rest between two radicalized, politically charged phases.

Twitter: @alessandrolanni