Reviewing media coverage on migration: an overview from Europe

Since the start of the large migratory movement that has seen displaced populations trying to reach Europe through the Eastern and Central Mediterranean routes, four main studies have been conducted with the aim of understanding the media representation of migrants in European societies. Findings from Georgiou and Zaborowski (2017), who carried out a content analysis of quality press in eight European countries (Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Serbia, UK and Greece) over the course of 2015 for the Council of Europe, show that refugees had very limited opportunities to share their stories with the public through the media, and that the representation offered of them was mostly that of victims and silent actors. No information presented about their cultures or other aspects of their lives enabled the public to learn more about them, with a tendency of journalists to present a narrative that stressed the causal connection “between the plight of migrants and the wellbeing of European countries” (9).

Two-thirds of the articles reviewed emphasised negative consequences of refugee arrival, with positive consequences only framed within the moral rationale of empathy and solidarity of the European populations. Concerningly, refugees were also predominantly described in the press as nationals of a certain country (62% of articles in the sample). Only 35% of articles distinguished between men and women among the refugees, and less than a third of articles referred to the refugees as people of a specific age group. Similarly, only 16% of articles included the names of refugees and as little as 7% included their professions. Without individual characteristics, refugees are implied to be of little use for European countries (as they seem to have no profession), inspiring little empathy (becoming dehumanised and de-individualised) and raising suspicion (as the absence of gender distinction aids the narrative of refugees being mostly young men in search of better opportunities).

Through a review of media coverage on refugees and migrants in Italy during the turbulent year of 2015, featured in a report from the Ethical Journalism Network (EJN), Macannico (2015) has highlighted how hate-speech dominated the press through the reporting of local politicians’ stance on this topic. Despite the occasional counterbalance with an ethical attempt of journalists to abide by the Charter of Rome (which regulates media reporting on migrants in Italy) the coverage of a small number of outlets was particularly alarming throughout the year.

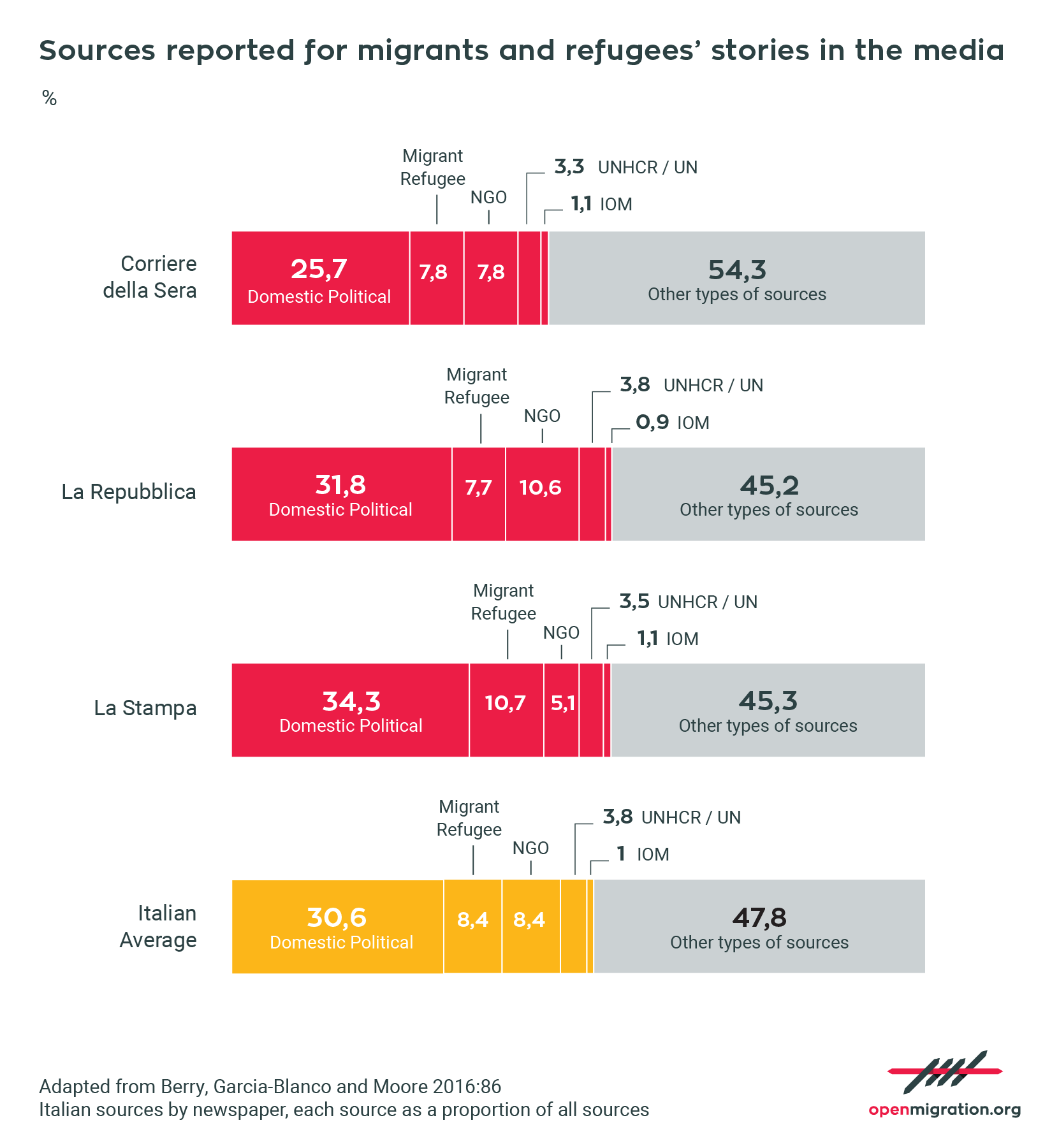

In a UNHCR report, Berry, Garcia-Blanco and Moore (2016) have explored what was driving media coverage in five different European countries – Spain, Italy, Germany, the UK and Sweden – in the journalist reporting on refugees and migrants between 2014 and 2015. The Italian sample, in particular, consisted of 300 stories published in the three main newspapers: Il Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica and La Stampa. Findings were overall fairly homogenous across the sample, and led the researchers to identify “[…] a dominant focus in the news media on recent migrants, that seems to eclipse the contribution and successful integration to Italian society of those who have already settled” (22).

Data from Berry et al. (2016:86) identify the types of sources the sampled press accessed for their news reporting (as shown in the graph below). Overall, as the authors explain, when migrants were given a voice, it was mostly to talk about the reasons for leaving their countries, the ordeal of their journey to Europe, and their experience of being trafficked. Yet, based on the findings from their analysis, most of the newspaper coverage did not actually report any of the reasons as to why people had tried to get to Europe.

As the literature highlights in a study from the International Centre for Migration Policy Development, the current migration story in the media is told in two voices: one conveys the emotional coverage of human loss through iconic images of people’s suffering, while the other one talks about the hard realities of massive movements of population with the potential to disrupt the living conditions, security and welfare of host communities (ICMPD 2017). In essence, too often, the representation provided is one that dehumanises migrants and leads to a perceived sense of social crisis, even when no crisis is taking place. The media influence this public’s perception by building an ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomy that emphasises differences rather than commonalities (Figenschou et al., 2015).

Additional studies that have been conducted on the topic of media coverage on migration in recent years include the works of WACC Europe (2017); Oxford University Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, through their Reminder project (2019); and the European Journalism Observatory (2020).

At the end of 2018, key informant interviews were held with one Spoke-person / Communication Director / Press Officer of six of the main organisations who have been working on the migrant response in Italy in recent years. These included: UNICEF, InterSos, Médecins Sans Frontières, Emergency, IOM and Oxfam.

In addition to the collection of a different type of data from the one gathered through content analysis, this inquiry focused specifically on refugee children and adolescents, in order to provide an additional lens in the area of media representation of migration. The aims were:

- To identify how NGOs/UN agencies communicate with the media on issues related to refugees;

- To understand how these organisations view the current account that the media are providing on refugee children and adolescents;

- To learn their perspectives on how the representation of these groups can be improved in the media.

The answers offered by the interviewees have been helpful to identify a set of critical points in relation to both the organisations’ approach to media relations in the area of refugee children and adolescents, and to their informed views in regards to current and future journalist reporting in this field. They have also been useful to recognise directions for a more contributive narrative of these vulnerable groups.

The representation of refugee children and adolescents: problems and possibilities

- Communication strategy

With reference to refugee children and adolescents, the organisations participating in this study discussed a number of core elements from their communication strategy related to these groups. Firstly, their approach with the media is based on the idea of ‘protection’ as a key driving principle in their media relations activity. This is also supported by a direct effort, in their communication, to avoid portraying children as victims and present information that wants to protect children from an instrumentalisation of their stories. From a more technical stance, parental or guardian consent is rigorously sought where required, while the use of images that identify children are avoided.

All the organisations agree that the media are typically interested in stories about children, and that one is more likely to gain a journalist’s attention on the topic of migration when communicating about minors than adult migrants. The general impression on this point is conveyed effectively by this interviewee:

A child creates a lot more empathy; in the eye of the public opinion, the image of a child is always stronger. It has always been a frame that media communication has used to move the public.

Yet, too often this leads to an oversimplification of the phenomenon of migration, which is also underlined by another respondent, who explains:

Overall, when presenting a problem about minors who have experienced suffering or violence, the public tends to listen. However, this means that we are only offering pieces of a puzzle, a puzzle which would instead be useful.

- Factors driving journalist reporting

Violations or lack of rights impacting a minor have been recognised to be part of the factors that drive journalist reporting on refugee children. A frame of pity is largely applied to the coverage, with a tendency to focus also on physical violence and tragic episodes, such as the instances of shipwrecks in the Mediterranean. As an interviewee states, “Usually, if migration is given a more ‘human’ angle on the media is when we talk about a dead child […]. Yet, even this does not last long. There is a moment of peak and then it goes back to silence…”. Another informant offers an important reflection that brings to light the consequences of this type of focus:

When communicating about children, I find it much easier to get the attention and empathy of journalists. When there is a shipwreck, for example, one of the first questions I get from journalists is ‘how many children were on board?’. This is because if the journalist writes ‘there were also 10 children on board’, sadly the article becomes a more “catchy” article; it is more moving, more impressive, it can make the front page. If it’s only adults dying, it’s not the same. If there are minors involved, journalists know that piece of news becomes more dramatic. So from this point of view, we can say that the tragedy of children as migrants simplifies the work of sensitising the public opinion.

There is an additional, significant and contrasting impact that this focus of journalist reporting on child migrants has, as this quote exemplifies:

The key driving factors in journalists’ media coverage of minors are tragic events that are not related to the challenges of daily life that migrant children experience but that make the news. Very often the child is left out of media communication altogether, with a focus on the criminality of migrants in general, which is a newsworthy item. Or what makes news is the underage drug dealer. There is a narration that is more and more based on fear, and also the child and the adolescents have entered this narrative. It is not true that Italians don’t want refugees: Italians must be put in a position not to fear refugees.

Within this context, and in addition to the five core principles of ethical journalism, the EJN has compiled a concise reporting guide that is specific to migration. The points expounded in this guide are useful to address the problem highlighted by this respondent. Similarly, the Media Diversity Institute has released a useful manual on how to report migration and counter hate speech.

- NGOs/UN agencies as sources

Findings show an overall consensus and perception that the organisations are used regularly by the media as authoritative sources on migration (in contrast with the small percentage indicated by Berry et al. 2016). As one of the respondents put it,

organisations like ours become a channel, a key source for journalists, because we are on the field, we see things first, starting from boat arrivals and security issues inside reception centres. Hence, we become like a sort of press agency: we are the first to provide information, we are the first to explain and tell.

It was specified by some, however, that this was more the case for the left-wing press. Some of the interviewees acknowledged and praised a number of journalists they have built positive relationships with this press, and who have helped to tell stories that would have otherwise remained unheard. The right-wing press appears to portray not only migrants, including children and adolescents, under a negative light, but also the organisations themselves. Information concerning one of the organisations in particular, has often been presented by this press without conducting any fact-checking or allowing relevant representatives to speak, according to one of the respondents.

In relation to media practices in this context, the National Union of Journalists for UK and Ireland, through a collaboration with UNHCR, has published useful guidance for journalists on refugee reporting.

- Children as sources

When it comes to refugee children and adolescents as sources, on the other hand, there is a shared concern about the potential dangers of putting journalists directly in contact with minors, and a general tendency from the organisations to “shield” minors from direct media exposure. Some of the interviewees attributed this to reasons related to the protection of the minor from a risk of instrumentalisation. Others mentioned the possibility of the child been asked to tell the story of their journey and the struggles experienced, which is what journalists want to know but often leads to re-traumatisation. Another informant discussed the complex bureaucratic challenges to overcome in order to allow a minor to speak in media, which some journalists and organisations do not have the time or resources to deal with.

The role of field staff in these organisations is also that of collecting the voices of children and adolescents (also thanks to their language skills), which are then presented to journalists through the organisation’s media relations activity. One of the interviewees reflects critically on this process:

In general, we still don’t talk about stories, and migrants are not used as sources. We talk about migration without the voices of the migrants, but mostly with those of the Italian politicians and journalists. And we, NGOs, are also a little bit responsible for that, as we are speaking on their behalf.

- Problems arising from the current narrative

When asked to discuss problems caused by the current narrative, a number of issues were identified by the respondents, particularly in reference to the impact this is having on the public. The way the narrative on refugee children and adolescents is currently shaped leads to prejudice and conveys a very superficial idea of these groups, which creates short-term empathy. The focus on numbers and geopolitical issues related to the areas that minors come from has also the effect of dehumanising them, while the loud voice that politicians are given on the media has a very negative impact on the perception that the public is developing, which is becoming increasingly less accepting. This quote expresses clearly what the result of the current representation is:

Communicating about refugee children and adolescent has become incredibly hard at the moment. We have gone from a country who was smiling, compassionate, informed, ready to help, to one that is tired, scared, violent, intolerant.

- Differences in the representations of refugee children and refugee adolescents

Lastly, differences in children and adolescents’ representation in the media were also recognised, with an agreement about journalist reporting on younger children being more likely to generate solidarity. As one of the informants indicates:

If we talk about children, the public is more likely to feel compassion and more acceptance. If we are talking about adolescents, looking like young men, there is already a different reaction.

Adolescents are often regarded, even in the media, as young men, and the right-wing press, in particular, fuels this representation also through the use of certain images, according to the interviewee. There is often an attempt to convey the idea of the adolescent as not being a real adolescent, in order to elicit fear; hence, due to the portrayal offered of them, this group does not generate the same kind of empathy as younger children do.

How journalism can make a positive difference

In addition to emphasising the need for more positive stories, respondents presented their informed views on what journalist reporting should focus on in order to provide a more accurate narrative and related representation of refugee children and adolescents. These can be summarised in the following points:

- Children as right-holders – Representing minors as empowered individuals rather than hopeless victims could develop more acceptance from the public, allowing them to see the potential that refugee children and adolescents have to contribute to the Italian society and counteracting the current perception of people in constant need of support;

- Their arrival in Italy – The Italian public is not informed about what children go through after their arrival, along with the administrative, legal, and social challenges they face. More awareness on this would help to paint a more accurate picture of the complex situation these minors face in their new reality;

- The integration process – Successful stories of integration should be presented to the public regularly. Here, the element of ‘regularity’ in this communication is key. While the media do, at times, present the experiences of migrants who have successfully settled in their host community, this is not done with enough consistency to develop in the public a stronger sense of acceptance for and a stronger familiarity with those who arrive, especially in the case of children;

- The commonalities between refugee children and Italian children – focusing on the similarities of the experience of being children, rather than highlighting the differences in the two journeys of the local and the refugee, would offer a representation that could facilitate the social inclusion of refugee children and adolescents.

In the words of one of the informants of this study, “We need a journalism that is more ‘constructive’, [one that is] key to stop offering only bad news and instead presents an investigation that not only looks into, of course, a situation of hardship, lack of security and suffering, but that also puts at the centre what can be done or what has been done to address that.” Similarly, another respondent suggested that “the focus should not be on the child itself, but on a series of elements that determine the current circumstances of such a vulnerable category, and what the solutions to these issues should be”. Interestingly, the study from WACC Europe (2017) has also underlined that “sympathetic journalism runs the risk of over-emphasising the refugee as a victim. Thus, rather than sympathy, journalists should strive for empathy, allowing the person to express her or himself and covering the issue from a perspective of understanding, based on facts” (6).

From the views of the key informants from the participating organisations, the adoption of specific communication strategies and techniques has been recommended in order to begin offering a more helpful representation of refugee children and adolescents:

- there is a need for an overall reframing of stories on refugee children and adolescents, which should not only present positive cases but also provide members of the public with an understanding of how they can personally contribute to those successes. Rather than leaving members of the public feeling as helpless bystanders after media exposure, these stories should also communicate what solutions are available. One of the ways in which this new framework for reporting can be achieved is by creating alliances between NGOs/UN agencies and the media, looking for those journalists and outlets that are more available; facilitating a shift is helpful in order to open up spaces that are different, to exert cultural pressure, and to make sure that the migration story is not only told in relation to specific news items that typically carry a negative undertone;

- getting cultural mediators to speak with journalists is another method to present stories of migrants, including the experiences of children and adolescents, in a positive and informed way. Cultural mediators are often refugees themselves, and an example of a positive story: they have fled a dangerous situation, at times at a young age; they have integrated successfully in the Italian society, and they are now not only employed but also trying to help others in their situation through their job;

- media reporting that reveals a clear and tangible thread between the two realities of the local, on one side, and the migrant, on the other side, encourages the formation of a bond between the member of the public and the refugee child. This is crucial to enable the public to visualise what links the identity of a local child in their immediate context, to that of a child coming from another part of the world, who arrives to Italy for reasons that are very complex for the public to comprehend – especially when no proper account is offered. At the same time, targeting also local young people to create this connection and work on developing empathy, understanding and acceptance is essential. The younger generations are the ones that will have to live side by side with the current child migrants: the media play a key role in contributing to positive social change by educating the youth so that the bases are laid for a more informed and inclusive society.

A vision for change

While the representation of refugee children and adolescents in Italy is driven by a range of dynamics influencing the media landscape, the ideas presented here offer another angle for exploring the narrative, one that moves away from a media content analysis and presents informed views of the communication context. The perspectives on this representation from the organisations that have been involved in the refugee response in Italy, are helpful to open a space for reflection on the impact that the current narrative is having on society; they also allow us to consider ways in which the narrative can be reframed, with a vision towards a broader social change that involves a shift in the way the local public experiences migration, particularly in relation to the struggles of children and adolescents on the move.

There is no denial that ‘media in the frontline countries of the European migration and refugee crisis could produce stylish and professional journalism to be proud of in a country where media, slowly but demonstrably, are learning from their mistakes’ (Macannico 2015:31). This is why the concepts introduced here want to be a contribution in enhancing the understanding of and in building up media practices in the context of migration, in order to reflect on and develop approaches that can effect positively the long-term situation of refugee children and adolescents, both during and after this time of displacement.

References

Berry, M., Garcia-Blanco, I. and Moore, K. (2016) Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU: a content analysis of five European countries, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Geneva

Figenschou, T.U., Beyer, A. and Thorbjørnsrud, K. (2015) The Moral Police. Agenda setting and framing effects of a new(s) concept of immigration, Nordicom Review, Vol.36, No.1, pp.65-78

Georgiou, M. and Zaborowski, R. (2017) Media Coverage of the “Refugee Crisis”: a cross-European perspective, Council of Europe, Strasbourg

ICMPD (2017) How does the Media on Both Sides of the Mediterranean report on Migration? – A study by journalists, for journalists and policymakers, International Centre for Migration Policy Development, Vienna

Macannico, Y. (2015) A Charter for Tolerant Journalism: media take centre in the Mediterranean drama, pp.25-31 in White, A. (Ed.) Moving Stories. International review of how media cover migration, Ethical Journalism Network (EJN), London

WACC Europe (2017) Changing the Narrative: media representation of refugees and migrants in Europe, World Association for Christian Communication – Europe region (WACC Europe) and Churches’ Commission for Migrants in Europe (CCME), London

Contacts

Dr Valentina Baú|[email protected]|Linkedin|Academia.edu|

Cover: A young guest at Casa Saltatempo Brodolini 24 in Cinisello Balsamo. Photo by Marina Petrillo, 2017.