His name was Alfatehe-Ahmed Bachire, he was 17 years old, and he came from Sudan. He is the latest dead migrant at the French-Italian border, drowning at the mouth of the Roja river on June 13. Some witnesses report that he was simply attempting to retrieve a shoe in the water, an accident with a tragic outcome. According to Intersos, the NGO that provides healthcare and legal aid to those migrants outside the reception system in Ventimiglia, his death is not a simple fatality. Rather, it is a consequence of the utter degradation in which those who came here to cross the border have been living for months.

“Our government cannot close its eyes to this deeply unfair death,” Cesare Fermi of Intersos says, “because it is the result of the persistent and shameful degradation of the area around Ventimiglia. A critical situation that has been deliberately worsened by a policy based on militarisation, repression, and rejection. On the French side, the Border Police arbitrarily refouling minors, and roundups and deportations on the Italian one.”

The railway bridge across the Roja river, Ventimiglia (photo: Michele Luppi)

This is not the first migrant death in the river running through Ventimiglia. On November 21, 2016, a man was swept away by the current; his body has never been found. A total of 11 migrants have died at the border between Italy and France since September 2016: eight of them were killed in their attempt to cross it, three died while they were still in Ventimiglia. Besides the two victims mentioned above, another migrant was hit by a scooter on January 4, 2017, near the Red Cross accommodation centre in Ventimiglia’s Parco Roja. The Italian driver lost his life in the accident as well.

According to the statements of the border police during the press conference on the eve of the G7 summit in Taormina, 17,048 refoulements were carried out in 2016 at the border crossings of Ponte San Ludovico, Ponte San Luigi, Olivetta San Michele and Fanghetto, at the Ventimiglia railway station, and at the A10 motorway gate.

“The French government decided to reintroduce border checks on June 11, 2015,” says Maurizio Marmo, director of the Caritas in Ventimiglia-Sanremo. “This is the third summer in a row and, compared to the same period last year, numbers have doubled.”

The Red Cross camp accommodates about 300 migrants, but far more live in the city. About one hundred women together with children under the age of 16 have found shelter in the Church of S. Antonio in the neighbourhood of Gianchette. Many other migrants, around 300 or 400, spent a number of weeks in an informal camp on the Roja riverbed until June 26. On that date, the municipality of Ventimiglia ordered the evacuation of the area and fear pushed a group of about 400 refugees to set out all together towards France. Most of them were caught by the French authorities in the following hours and readmitted to Italy. Over one hundred were taken by bus to the hotspot in Taranto.

Migrants camped under the railway bridge across the Roja river in Ventimiglia (photo: Michele Luppi).

According to Antonio Suetta, Bishop of Ventimiglia, “these kind of situations expose migrants to major risks, and over the last few months have even claimed some victims. My main concern is what will happen to foreign unaccompanied minors, a group that represents a large part of the refugees in Ventimiglia. They should receive proper accommodation.”

In addition to those who have lost their lives, dozens of migrants have been wounded, some of them as young as Yasir, a 20-year-old from Sudan. When we meet him along the Roja river, his foot is noticeably bandaged. “I hurt myself three days ago,” he says, “on one of the paths that lead to France. I had already crossed the border when the police saw me. I tried to run away but I slipped on a heap of stones and got injured. Then they caught me and took me back to the border.”

Border deaths

On March 21, the French newspaper Nice-Matin reported the finding of a dead migrant on the French side of the mountain. Two days before, a guest had been noticed missing at Parco Roja but searches on the Italian side had been unsuccessful. His body was retrieved along the Grimaldi track, at the border between Menton and Ventimiglia, one of the crossing points used by migrants. It is referred to as the “death pass” because of its roughness; in the past, it was secretly used by antifascists and smugglers to cross the border.

“The dead body was found after several days and we cannot rule out the possibility of other victims we don’t know about,” Maurizio Marmo says. “Unfortunately, the track has many forks, and if you don’t know the way, you could end up on the edge of a ravine.”

On September 6, 2016, a young African boy trying to evade the border police and whose name is still unknown fell off a viaduct on the A8 motorway outside Menton near the village of Sainte-Agnès. One month later, on October 9, the 17-year-old Eritrean girl Milet Tesfamariam was hit by a truck at the French border on the A10. She was walking with some of her relatives through the tunnel after the Ventimiglia gate, just before French territory. The driver declared that he saw the group of migrants crossing the road and tried to slam on the brakes, but was unable to avoid the girl.

Less than two weeks later, on October 21, the French newspapers reported that another young migrant was hit by a car headed for Italy on the A8 near Menton. “According to the police,” Le Parisien read, “the presence of several people on this stretch of the motorway that leads from Italy to France had already been reported at the beginning of the night. Some of them were found and taken to the border police.”

Dangerous trains

Although migrants are increasingly caught trying to cross the border on foot, over the last ten months, trains have continued to cause the greatest number of casualties. On December 23, in the town of Latte, near Ventimiglia, a local train bound for Nice ran over a group of migrants walking towards France along the Ventimiglia-Menton lines. A 25-year-old boy from Algeria ended up on the ballast and died instantly.

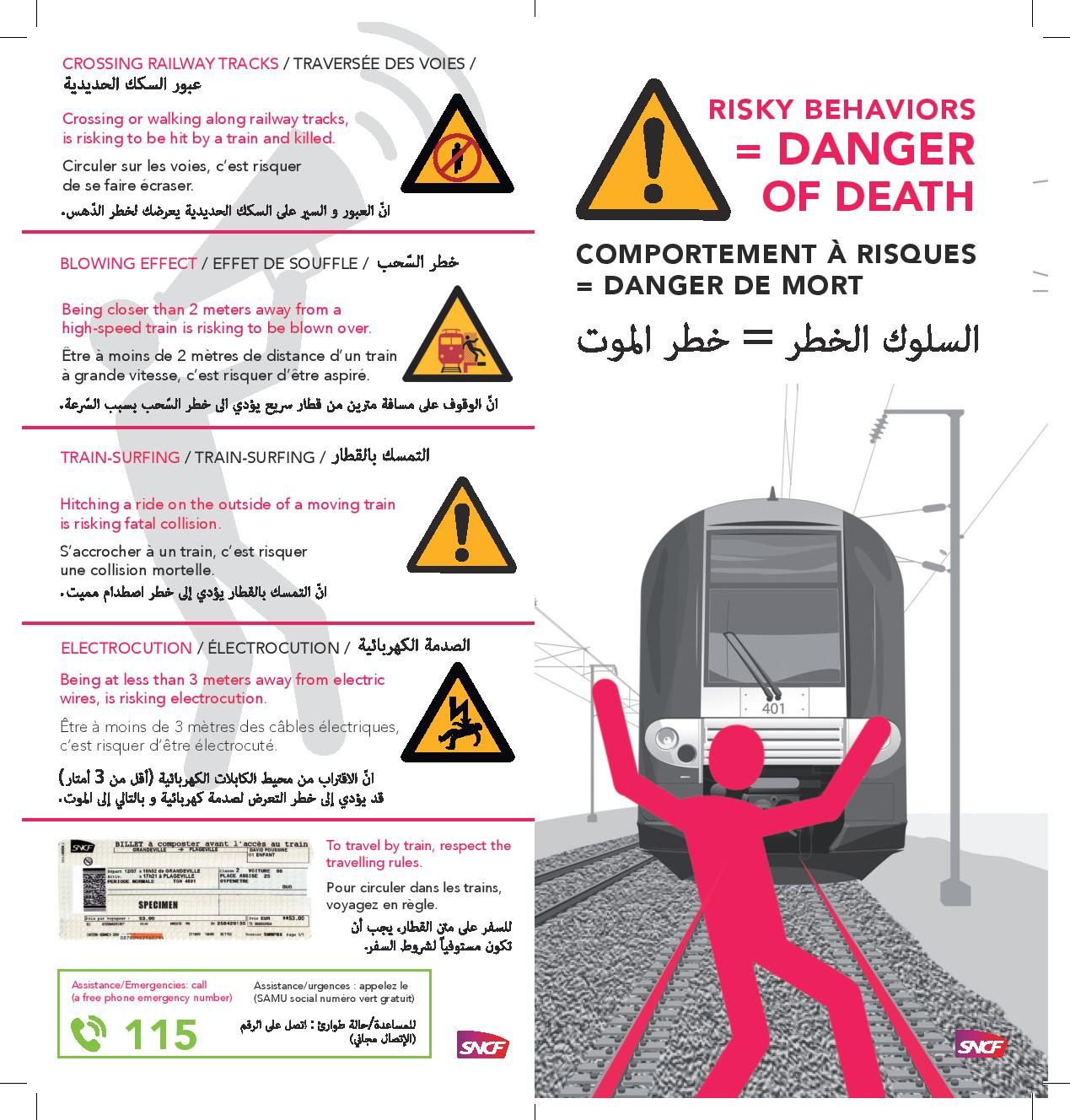

The Mediapart report reveals that, in accordance with the procedure of the French railway company Sncf, in cases of accidents involving other people, the engine driver has to stop, get off to inspect the tracks, and inform the block post. At that point, traffic must be interrupted until police and first-aiders intervene. Furthermore, it is a winding route, with unlit tunnels and very poor visibility. A train needs from 300 to 800 metres to stop completely. This is why many accidents happen in the dark: border crossings are more frequent early in the morning or at the end of the day.

Daniela Zitarosa, legal operator of Intersos, explains, “Friday is one of the most stressful days because it’s market day and many French come to Ventimiglia to go shopping. Migrants try to take advantage of the confusion to get on the trains.” Some of them hide under the seats, in the banker, or in more dangerous places: electrical rooms, gangways, tool cabinets. Others try to enter France by walking along the railway tracks. On February 5, a migrant was hit in the Dogana tunnel, the last one before the border, by a local French train headed for Italy. The victim was with other migrants. Twelve days later, at the Cannes-La Bocca railway station, the dead body of an African man was found on the roof of a train; he had been electrocuted and was stuck in the pantograph, the device that connects trains and trams to the overhead high-voltage wires. On May 20, at the same railway station, the Sncf cleaning personnel found the electrocuted body of a 30-year-old from Mali in the small electrical room of a local Ter train.

Following all these deaths, the French railway company drew up an informative flyer warning people of the risks, and have asked the associations operating in Ventimiglia to help distribute it. In this way, they hope to prevent further deadly accidents.

The warnings published by Sncf, the French railway company, in an attempt to avoid fatal accidents involving migrants (Sncf).

Nameless dead

The number of the dead is not the only shocking thing at the border of Italy and France. It is also very difficult to find information about the victims and the current location of their corpses. As Marmo explains: “Unfortunately, most of the migrants died in France and we don’t know whether or not they were buried and, if they were, how. From this point of view, it’s hard for us to have an overview of the situation.”

But there is one person in particular every one remembers with special fondness at the Church of S. Antonio – the positive symbol of the city’s reception of migrants. Milet Tesfamariam, the 17-year-old Eritrean girl hit by a truck on October 9, was one of the twenty thousand migrants the church has accommodated since its opening on May 31, 2016. “We celebrated her funeral on October 15, here in the same church where she slept the night before she died,” Father Rito Alvarez says. “Dozens of migrants attended, most of them Eritrean, but there were also a lot of Italian and French volunteers as well as normal citizens.” Among them was Milet’s cousin who lives in Rome and came here in order to identify the body. The parish even organised a collection to raise the five thousand euros for the body to be repatriated. “It seemed the least we could do to restore her dignity,” the priest says.

The funeral was also attended by Antonio Suetta, the Bishop of Ventimiglia, who gave a harsh homily (the second part of which is available here): “Milet is a victim of the unfair regime of her country from which she escaped. A country everyone knows, but no one cares about. Milet is a victim of our borders–as legal as they are unfair–when they’re closed in people’s faces and inexorably shut before their cries for help. Milet is the victim of a society which claims to be civilized, which parades principles like brotherhood, freedom, and equality, but where people are persecuted and killed in the name of those principles. A society that has proven unable to apply these principles impartially, where some are more of a brother, freer, and more equal than others. Our civilization should be ashamed of this injustice. Milet is a victim of the piles of files that lie for too long on the desks of those in charge, of the unfair procedures that fail to do justice to the poor asking for help.”

UPDATED: shortly after this article was published in its original Italian version, we received news of a twelfth death: a migrant whose nationality is still unknown who was run over and killed by a truck in Latte (as reported on the map).

*UPDATED: sadly, more deadly incidents are being reported in the area of Ventimiglia: on May 24, 2017 a man from Senegal was found dead, he too electrocuted in the electrical room of a French train that had left from Ventimiglia. On August 16, 2017, a 36-year old Iraqi migrant died hit by a train at the mouth of the tunnel in the Puglia zone in Ventimiglia.

Translation by Lucrezia De Carolis. Proofreading by Alex Booth.

Cover photo: the overhead road sign at the Ventimiglia tollgate on the A10, the last one before the French border, summer 2017 (Michele Luppi)