For many years the issue of migration has been a relevant topic in both the public and political discourse within EU countries. However, since 2015-2016, when a large number of refugees and asylum seekers – mainly from Syria, due to the war – headed towards the borders of the EU, the phenomenon of migration has been increasingly discussed and linked to a context of “crisis”, both by the governments and by the media.

Starting from the latter, University of Leuven researchers Stefan Mertens, David De Coninck and Leen d’Haenens, as part of the HumMingBird project, highlighted how the impact of media, from television to digital newspapers, and defining migration as a constant “crisis” can contribute to the emergence of racism and hostility towards migrants, through two comparative analyses carried out on a selection of EU countries – Italy, Spain, Hungary, Belgium, Sweden and Germany (Cross-country comparisons of the media impact on anti-immigrant attitudes and A report on legacy media coverage of migrants).

The research was conducted through an online survey, collecting quantitative data on attitudes towards those who, in the research, are defined as outgroups (immigrants, refugees); trust in the media and governments’ attitudes towards migration among the adult population aged between 25 and 65 within the six European countries mentioned above. In collaboration with Bilendi, a Belgian polling agency, the researchers conducted interviews reaching a dataset of 9,079 people (approximately 1,500 per country).

From the research conducted, it appears that Italy stands out among the countries that generally consume more news on public service media than those of tabloids. In Hungary and Spain, however, the opposite occurs.

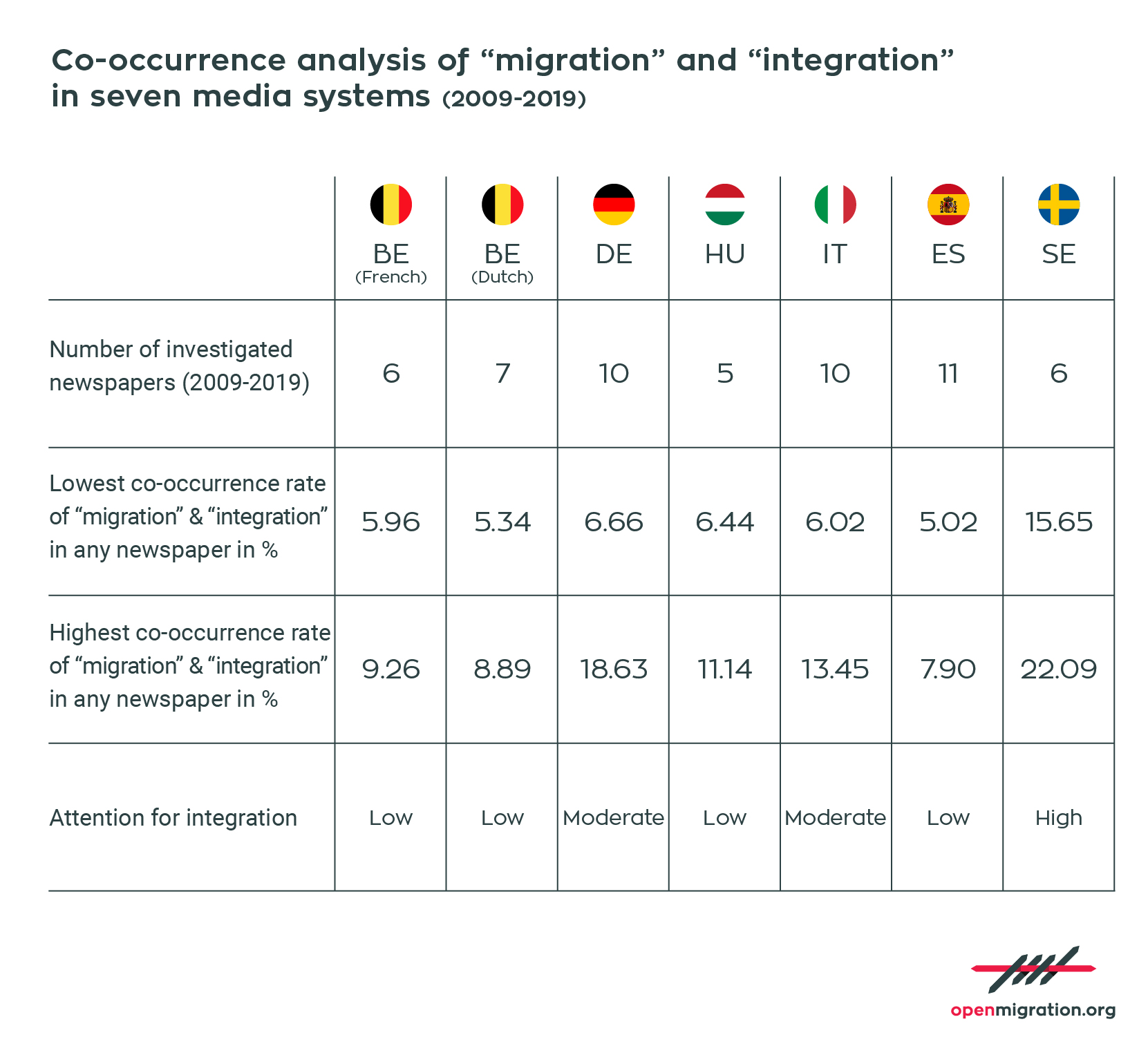

The researchers then also conducted an analysis to understand the kind of perceptions that people develop about migration, based on the type of information coming from media consumption. With regard to TV news consumption, public service news consumption and local news were found to be associated with less perception of actual and symbolic threat, while news consumption coming from tabloids was found to be associated with greater perceived threat. In addition, the researchers conducted an analysis on the recurrence of the words “migration” and “integration” in the newspapers of the 6 countries. According to this analysis, Swedish newspapers, for example, have devoted a lot of attention to the link between migration and integration and, although it is not possible to deduce the tone or framing of the articles, it is possible, according to the researchers, that although Swedes were considered among the most open to outgroups, large-scale media attention to integration and migration in recent years has contributed to a paradigm shift. In Spain, on the other hand, which is the country where threat perceptions were lowest, as it is highlighted in the research, the rate of frequency with which the migration-integration link was used by the mass media was low.

According to the researchers, while these findings cannot definitively indicate any causal link between media content and threat perceptions, there appears to be some overlap in the importance attributed to this type of migration coverage in recent years.

In all the newspapers taken into account for the research, it was noted that the presence of certain keywords – for example “integration”; “criminality”; “terrorism”; “refugees” – depending on how they are used in the discourse, can lead to real consequences in the perception that the public has of migration. Taking the Italian public opinion as an example, the researchers took into consideration some national newspapers, placing them in a table with different political orientations (divided into left, centre and right) to analyse the words used, calculating the percentage of media coverage on certain issues to do with immigration. La Repubblica, La Stampa, Avvenire, Il Sole 24 Ore and Corriere della Sera were included in the centre group; Il Fatto Quotidiano in the left group and Il Giornale in the right group.

According to the research, the greater the perceived threat, the stronger the negative attitude towards immigrants. In the case of the media narrative perpetuated with respect to migrants, a fundamental role is played by the perception that people have when it comes to the impact on the economy and culture and traditions at a national level. For example, the research highlights that Il Giornale often includes the words “Islam” and “Muslims” – in a negative way – fueling hostile attitudes towards Muslim people. Furthermore, it is explained, Il Giornale is the only newspaper where exposure to outgroups is not correlated with higher scores in positive attitudes towards them.

Focusing on Italy, if one thinks of crime news articles in which the words “crime” and “immigrants’ are associated, the nationality or ethnicity of the person who committed the crime are highlighted, as if they were the main characteristics. The tone of readers’ comments on the webpages of the most important online newspapers, changes depending on the nationality or ethnicity of the offender or alleged offender. Associazione Carta di Roma (The Charter of Rome Association), in order to specifically avoid stereotypes, generalisations and prejudices based on the ethnicity of the person associated with a crime that has occurred, has always promoted the implementation of the ethical protocol for correct information on immigration issues in its “Linee Guida per l’applicazione della Carta di Roma” (guidelines for the application of the Charter of Rome).

“Avoiding ‘ethnicising’ news does not mean censoring certain information but selecting, from among the various characteristics of a person, only those that are truly relevant to understanding what happened”, the Association affirms.

In fact, “while it would be useful for understanding the story to write ‘an Albanian citizen was arrested at the station: he was wanted by the national authorities of Tirana’, the designation by nationality would be superfluous in a generic case of crime like ‘Albanian arrested after failing to stop at a checkpoint’. In the latter it would be suggested that the origin from Albania is relevant to explain the actions of the subject and would favour the automatic association of the reader between their nationality and the criminal act”.

There is often a tendency to criminalise an entire ethnic group, rather than analysing the specific case, precisely because it is about a clearly visible and identifiable minority, and therefore it is easier to exaggerate, exploiting generalisations to explain an event. However, this mechanism does not operate for the majority: if we take for example the cases of sexual violence in which white Italian people are involved, public opinion does not sway according to the origin of those rapists. On the contrary, if the offender is a person of another nationality, then the criminal act in question becomes a representation of all the people who are part of the same nationality, going so far as to infer that it is part of a culture that belongs to a certain ethnic group. In reality, in these examples, there is no difference in substance: both individuals have a lot in common, despite their different ethnicity or nationality. Considering sexual violence more or less serious because it is perpetrated by one or the other person, does not change what happened, nor does it place it in a different light. In this case, the focus remains on gender-based violence, a systemic issue that is common to all, regardless of where it comes from. However, racism arises where a newspaper ensures that there is a direct correlation between an event and nationality, even when the latter is not relevant to the news itself.

The narrative of migration, in Italy and in Europe, therefore often oscillates between two main concepts: criminalisation and the “crisis” framing of landings (whether by ship or otherwise). As far as the latter is concerned, the narrative often lacks of the description regarding the policies that actually negatively affect migrants. The distorted narrative on migration has already been disproved by the numbers that continue to decline from 2015 to today: “The continent that bears the burden of migration the most is Africa. According to an estimate by the World Migration Report, in 2020 alone, wars and famines transformed 21 million Africans into forced refugees. But most of them are internal refugees, people who have sought refuge in less fragile regions of their own country. Maybe with the hope of being able to return, sooner or later, to their homes”, Melting Pot reports.

Furthermore, this emergency rhetoric is wrong because it distracts from the real problem of this phenomenon, namely the lack of policies aimed at guaranteeing the right to freedom of movement – from the issue of visas, to the inequalities of passports (which is constantly highlighted by the Global Passport Index) to the contrast of the violent repressive policies of the borders in which, on a daily basis, the rights of migrants are violated due to systematic pushbacks.

Correct information on migration should not only be based on real data that can counter alarmist tones, but also on an anti-racist deconstruction of every aspect that can affect and cause international mobility – economic crisis, global inequality, climate change, conflicts. In fact, the researchers highlighted the importance of combating misinformation by encouraging institutions to understand the impact their words have on the attitudes of people, influenced by the media, towards immigrant citizens and other citizens. It would be important to encourage participation in cultural initiatives by all social groups, regardless of ethnicity or nationality, in order to create greater social cohesion.

This research study was produced within Humming Bird. Humming Bird is a Horizon 2020 research that aims to improve the mapping and understanding of changing migration flows.