The Italian lower house of Parliament has approved the decree-law on security and immigration, issued by the Council of Ministers in September and championed by interior minister Matteo Salvini. The new package includes several measures on international protection, the migrant reception system, and citizenship.

The draft passed in the Senate on November 7th, not without disagreements within the majority: all proposed changes had been rejected, while a major amendment by the government was approved thanks to a vote of confidence. According to several groups and experts, the amended version of the bill took an even harder stance on security and immigration. Eighteen MPs from the Five Star Movement wrote a letter to their group leader in the Chamber criticising the bill and submitting a number of amendments to the Constitutional Affairs Committee. However, these were all withdrawn, accelerating the legislative process.

The new measures include the end of humanitarian protection, a downsizing of the Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees (SPRAR), longer detention times in repatriation centres (CPR) and hotspots, withdrawal of citizenship for terrorism crimes, tighter restrictions for permits, and the revocation of refugee status for those convicted of certain crimes.

The Baobab camp just after being cleared. Photo by Andrea Oleandri

The abolition of humanitarian protection

The decree-law on immigration and security also eliminates humanitarian grounds for granting protection. This type of permit was introduced in Italy in 1998 under the Consolidated Act on Immigration, in addition to subsidiary protection and what the status of political refugee is. It was issued to people who were not eligible for asylum but had nonetheless “serious reasons, in particular of a humanitarian nature or resulting from constitutional or international obligations of Italy” to remain in the country. Also eligible for humanitarian protection were people fleeing war, natural disasters, and other grave events in countries outside the EU, as well as victims of persecution or exploitation.

Humanitarian protection was therefore tied to specific forms of vulnerability. As Stefano Catone, a writer at Possibile, explained, Italy had thus ensured the full implementation of Article N. 10 of its Constitution, which mentions foreign nationals who are “denied the actual exercise of the democratic freedoms guaranteed by the Italian constitution”, as well as Article 33 of the Geneva Convention, which prohibits states to “expel or return a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontier of territories where his or her life or freedom would be threatened.”

In recent years, Italy has granted humanitarian protection liberally. According to Matteo Villa, a researcher from the Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), it was the most common form of protection granted to foreigners in the country from 2014 to 2017. Out of 130,000 applications filed last year, 25% were granted humanitarian protection; 52% were rejected; 8% were granted refugee status; another 8% were granted subsidiary protection; and 7% were granted other types of protection.

Under the decree law on security and immigration, this type of protection will no longer be granted. The rationale for this decision is that the definition of humanitarian protection is too uncertain, leaving “too wide a margin for extensive interpretation” and creating too many “fake refugees” who are “running from no war”, as Salvini has stated repeatedly.

Most likely this will cause an exponential increase in the number of irregular immigrants. According to Villa, the end of humanitarian protection will lead to an estimated 130-140,000 immigrants losing their permits by 2020: “60,000 new irregular immigrants in addition to the 70,000 ones within the current situation.”

Humanitarian protection will be replaced by special permits of variable length for certain categories: those in need of medical care, victims of domestic violence or labour exploitation (in which case the worker has to lodge a complaint), those coming from a country that is in a temporary situation of disaster, those who have distinguished themselves through acts of civic valour. Other cases include those where the applicants cannot be returned to a country where they may be subjected to torture or persecuted on grounds of their race, sex, language, citizenship, religion, or political opinions.

According to Salvatore Fachile, an attorney with the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI), the measure is in violation of both the Italian Constitution and international laws: “The decree-law provides for a very limited form of protection, which is valid for one year and cannot be converted into a residency permit even if the beneficiary has found permanent housing. It can only be extended for a further year. During this time, only those on a humanitarian protection permit are allowed legal residence if they are in possession of a valid employment contract. Many of them are already integrated but are doing undeclared work, and will be inevitably pushed into a formally illegal status.”

Limitations to the right of asylum

The major amendment passed in the Senate introduces new limits to eligibility for international protection. These include a “procedure for patently unfounded claims” and the creation of a list of “safe countries of origins” curated by the Ministries of the Interior, Foreign Affairs and Justice and based on information provided by the National Commission for the Right of Asylum. Applicants from these countries will be required to demonstrate “serious reasons” for seeking protection. This, according to a note from the Italian Council for Refugees (CIR), constitutes “an inversion of the burden of proof, contrary to the general principle of sharing the burden between the State and the applicant.”

Asylum claims will also be rejected if the applicants may be repatriated in a different region of the same country that is deemed safe. According to CIR, “too much discretion is given to the examining body,” and “the possibilities for protection are severely limited.”

Furthermore, according to ASGI vice-president Gianfranco Schiavone, the concept of “safe country” is a risky one, as “asylum applications are by definition individual; that is, relating to each applicant’s specific conditions. Examining asylum applications on the basis of the ‘safety’ of a country introduces substantial prejudice in the process, as well as giving the executive branch a wide margin for political influence over the examining body.”

The dismantling of the SPRAR network

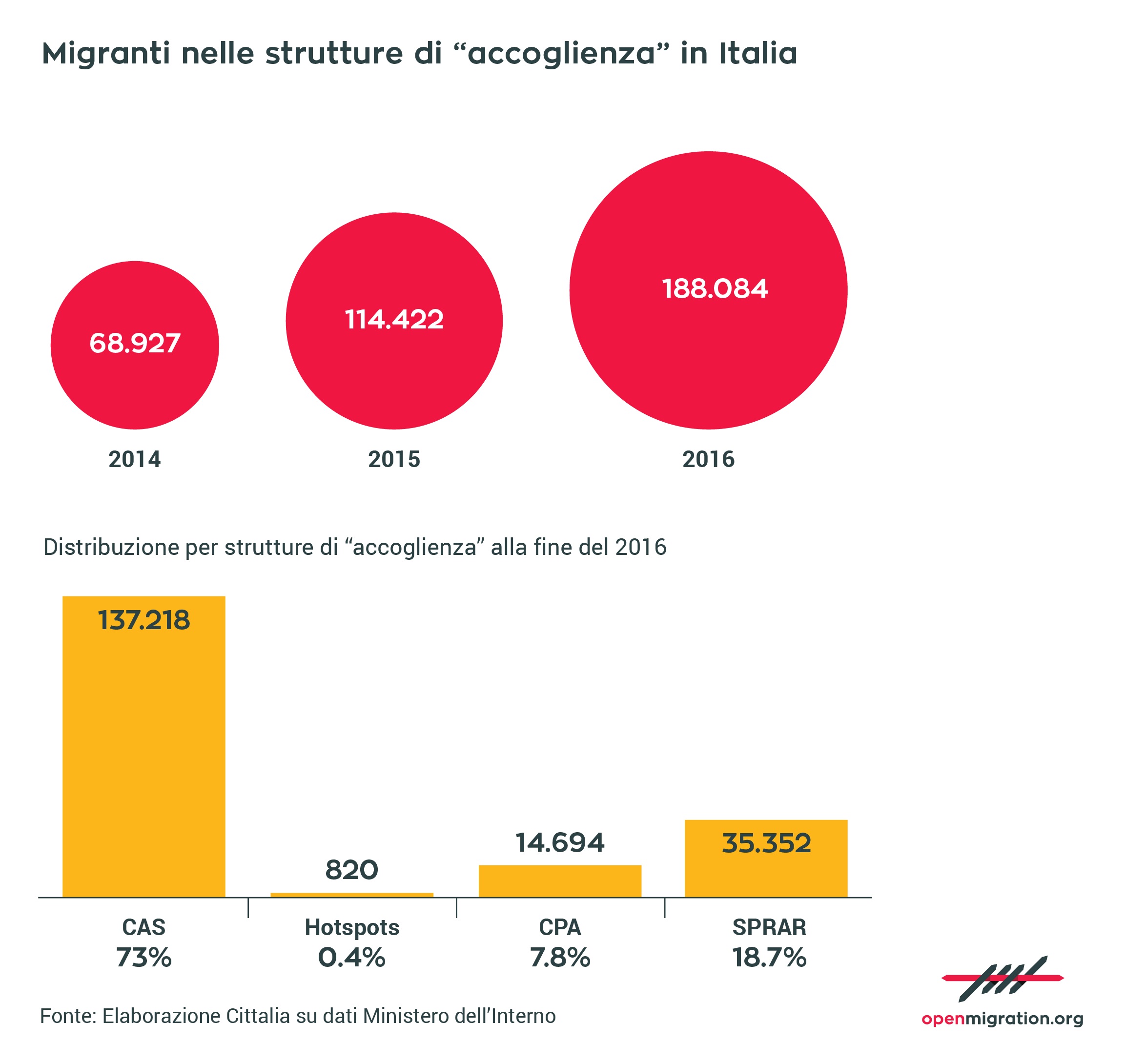

The new decree-law significantly limits access to the Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees (SPRAR), a public, decentralised network made up of local institution that implement reception as well as integration services. Previously, access was granted to asylum seekers and those who had been granted either subsidiary protection or refugee status.

Under the new law, only foreign unaccompanied minors, beneficiaries of international protection, and those in possession of “special” residency permits will have access to SPRAR. Asylum seekers with pending applications will therefore be cut out of the system.

The only available option to them will be the centres for extraordinary reception (CAS).

Until now, at least on paper, the CAS constituted the so-called “first-rung reception” where essential needs were met (identification, asylum proceedings, medical check-ups), while secondary reception included the SPRAR projects. Under the decree-law, this distinction is lost.

As the numerous human rights groups within the National Asylum Table have pointed out, this will lead to prioritizing large, collective reception centres with much lower standards. The SPRAR system has been so far “the only socially inclusive one, operated locally and with a fully transparent management of funds”, reducing the risk of criminal infiltration or speculation. According to data released in the latest SPRAR Atlas, in 2017 alone, over 25,000 beneficiaries have attended at least one Italian language course; 15,976 have attended vocational training courses and subsequent apprenticeships; 4,426 have found employment; and all the minors have been enrolled in schools.

A creative lab inside a reception facility (SPRAR) in Fabriano managed by GUS

According to ASGI, “Eliminating the SPRAR network and confining asylum seekers in government or emergency facilities only” may violate the Constitution, particularly article N. 117, as it would breach Articles 17 and 18 on the conditions for reception under EU Directive 2013/33. The decree-law does not include “a structured reception system that meets the minimum standards set by the Directive for reception in CAS; extraordinary centres would become ordinary, disregarding standards on language learning, legal orientation, support to vulnerable groups, mental health counselling, the protection of family life and normal living conditions.”

During a Senate hearing, SPRAR director Daniela Di Capua voiced her concerns over the lack of access to the local reception system for asylum seekers. These people, cut out from first-rung centres and deprived of tools for even partial autonomy – will be at greater risk from labour exploitation and criminal groups, creating new pockets of social marginalisation.

These concerns are shared by prefect and CIR director Mario Morcone, who fears that “the dismantling of the SPRAR network” will lead to “social exclusion that will inevitably mean more vulnerabilities for foreigners arriving in Italy.”

Cover photo via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)