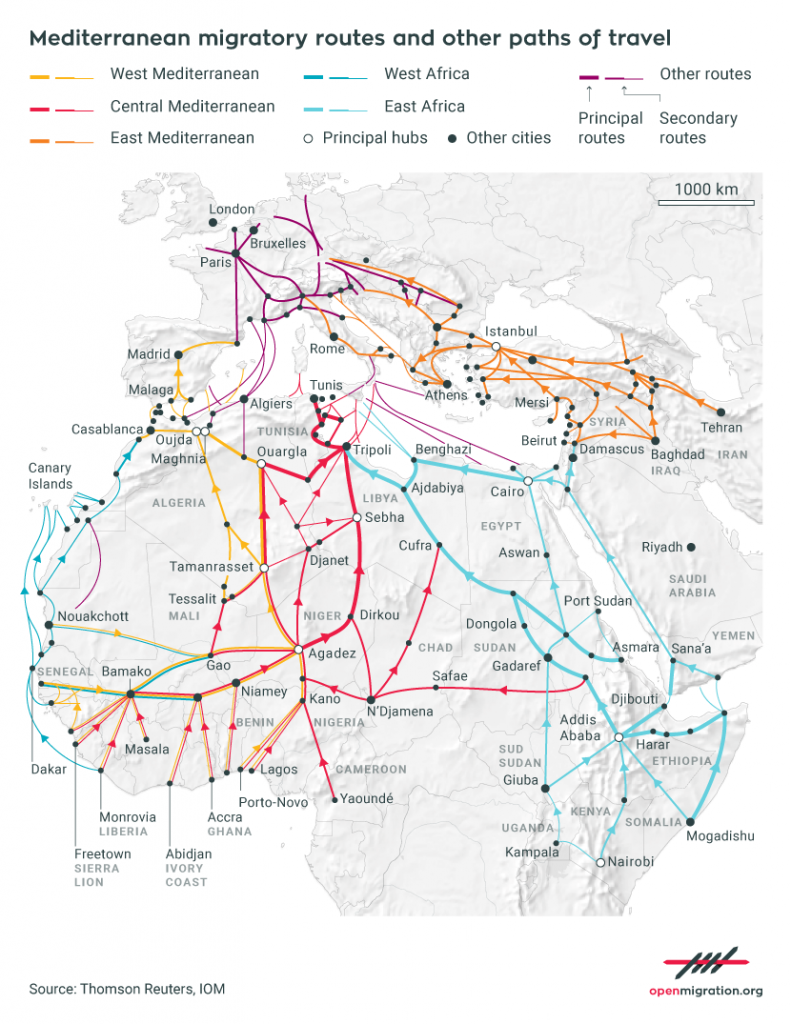

4,733. The death toll in the Mediterranean, ever since the UNHCR started counting in 2008, has never been so high.

It took almost 20 years before national, and then European, institutions began to think about those who did not make it to Europe, or were dead on arrival. And not only, if you will, because it is one of the most complex humanitarian challenges in history. The deaths in the Mediterranean, rather, are political, one of the interlinking causes of the European crisis, the tangible evidence of the discrepancy between reality and ideal. “For shame,” cried Pope Francis in the aftermath of the Lampedusa shipwreck of October 3, 2013. And on the same occasion, the Italian prime minister vowed that there would be “no more deaths,” knowing full well that history would prove him wrong.

However, that tragedy was a trigger. The first military rescue mission in the Mediterranean, Mare Nostrum, was launched shortly after. A convincing emotional response, at least in humanitarian terms. It can be no coincidence, then, if this year, when the number of dead and missing hit 4,000, Europe turned the Frontex Agency into the European Border and Coast Guard. Maybe it was because Frontex’s credibility had been plummeting.

But this is nothing new. Giving missions a different name is a ploy that has been used on other occasions. Just one example is the operation EUNAVFOR MED, a European naval patrol operating 12 miles off of Libya’s national waters, whose name was changed to Operation Sophia after WikiLeaks released restricted communications among high-ranking officers who discussed “military activities” to be held in the Mediterrean that must avoid “collateral damage”, namely migrant lives.” ‘Disrupting the business model of the smugglers’ was the declared aim of the mission.

Later in August, following a UK Select Committee report that described Operation Sophia as “failing”, the European Union’s Commissioner for Justice, Věra Jourová, wrote in her assessment that in the 11 months since its launch, EUNAVFOR MED had contributed to the arrest of 71 suspected smugglers and had destroyed 148 boats. But what about the casualties? There was no clear mandate, only the law of the sea, but, so the document said, over the course of one year the operation had saved 13,000 people.

What’s behind the figures in 2016

4,733. A sad paradox in the end.

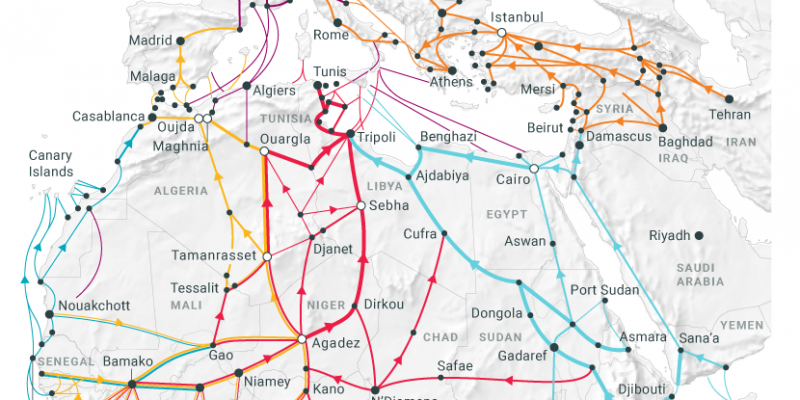

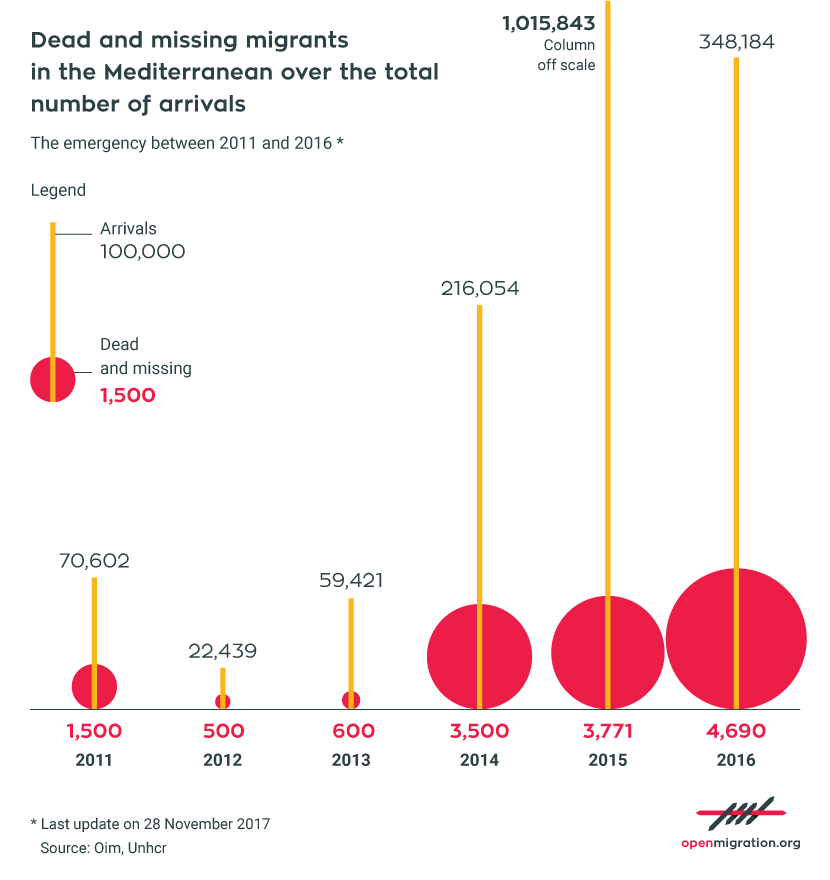

The closing year was certainly not the one that saw the most arrivals on European shores. The number of arrivals actually decreased by a third, mainly because of the controversial EU-Turkey deal (which might not last much longer, given Erdogan’s recent threats) that promised Turkey 6 billion euros in aid (to be paid in two 3-billion euro installments) along with the cancellation of visa requirements for Turkish citizens in exchange for the closing of the Balkan route, along which more than 800,000 people arrived last year. A questionable “quick fix” that does not, however, offer anything in terms of reducing casualties, for most deaths occur off the coasts of Libya or Lampedusa, along the central Mediterranean route.

This is why Italy is leading the increasingly small group of EU member states that are seeking to reach bilateral agreements with countries along the southern Mediterranean’s edge to stop migrants on extra-European shores. In the meantime, however, the Visgrád Group (Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary) is undermining all European policies on migration. Furthermore, internal disagreement in the EU is and has been compounded by the power vacuum in Libya: how can one negotiate with a country that does not even have a unified government?

On vessel tracking websites such as Marine Traffick and Vessel Finder, which are also used by the Frontex headquarters in Pratica di Mare, Italy, the southern Mediterranean is constantly marked by vectors representing ships in transit. Among these, since 2010 at least five have been deployed by NGOs with the aim of rescuing lives.

Why, then, are so many people still dying at sea? The first reason is that communication between the sea missions (NGOs, the military, Triton) and those coordinating rescue operations (the Port Captaincies in Rome) is difficult, especially since fewer and fewer migrants have satellite phones and, as a result, cannot send out distress signals. Coordinating rescue efforts means coordinating the search for boats in distress as well, but currently no European missions are deployed at sea with this goal in mind. Additionally, not all ships are suited to rescue operations, and it’s especially difficult to rescue passengers from cargo ships, as the shipwreck of April 18, 2015, clearly showed.

Naturally, there are also “political issues” linked to rescue missions. While, in theory, intervention is mandatory whenever lives are on the line, the reality is often different, as pointed out by MEP Barbara Spinelli in her preface to the Death by Rescue report, published on April 16. Sometimes, Spinelli said, Frontex units ignore distress calls. One notorious case was the institutional clash between Frontex and the Ministry of the Interior’s Immigration Department and Border Police (IDBP) in December 2014, which resulted in an official reprimand. Earlier in November, after receiving a series of requests for rescue, the Operations Control Centre of the IDBP in Rome had urged a Frontex unit to verify the presence of migrant boats in distress at a location outside of the Triton operative area. Eventually, the unit went to the reported location. As Klaus Roesler, director of the Frontex operative division at the time, wrote in a letter quoted by Spinelli, “Frontex maintains that a satellite phone call cannot be considered in itself a search and rescue event, and therefore recommends that steps should be taken to investigate and verify, and only later, in case of difficulty, should another maritime unit be activated. Moreover, Frontex considers unnecessary and inappropriate in terms of costs the use of an offshore patrol vessel for these initial verification activities out of area.”

Moreover, since no more European missions have a mandate to save migrants’ lives, confusion has ensued over who should respond and in which capacity. There are not enough ships deployed at sea to carry out all operations. A humanitarian operator who spent the entire summer on board with a mission in the central Mediterranean explained that certain military ships would not even mobilize despite being the closest to the location of a stranded boat, going so far as to even refuse to transmit their coordinates to the Port Captaincy. A military secret. “All the same, it cannot be denied that they do an important job,” she clarified.

And then there have been instances of delayed response because of Coast Guards from neighbouring countries shuffling off their responsibilities. This is exactly what happened between Malta and Italy – as Fabrizio Gatti has demonstrated in L’Espresso – and which resulted in the Lampedusa shipwreck of October 11, 2013 (one of the very few cases where it was possible to conduct an investigation). In its report, Europe’s Sinking Shame, Amnesty International analysed those shipwrecks which caused the most deaths in 2015, and concluded that the Triton initiative did not have enough ships to react in a timely manner. The January 22 incident: a boat transporting 122 people spent 8 days drifting around the Mediterranean. How was it not intercepted? It was only spotted some 2.5 nautical miles from Maltese shores. The final death toll was 34.

In order to fill this institutional vacuum, NGOs have deployed their own boats. With the exception of MOAS, all have chosen not to use drones to monitor the waters. Primarily for financial reasons: drones are expensive, and their advantages are not so clear. Out at sea, NGO crews still rely more on what is visible to the naked eye. Moreover, given their opposition to EU policies on migration, NGOs are reluctant to share any of their images with European missions. Even without the appropriate technology, indeed, “Frontex has asked for permission to share images of rescue operations, ostensibly to identify the boat drivers,” a humanitarian operator, who asked to remain anonymous, explained. In most cases, NGOs do not want to be complicit in the capture of people who are often, they believe, not involved in human trafficking.

Several officers from the Italian headquarters of Frontex in Pratica di Mare have confirmed that relationships between NGOs and the border patrol agencies are sometimes problematic, explaining that they have trouble conducting their investigations when the NGOs are the first to arrive. Another operator (who also asked to remain anonymous) admitted that missions at sea are “sexy” to NGOs, as shown by the number of NGO vessels currently at sea, a number that has doubled since last year. Rescuing migrants is at the front line of the solidarity business: “Everybody tries to do their part without damaging the others,” she explained. This is the norm, but there are some exceptions: last summer, someone who was “acting in good faith” and wanted to “get there faster” crossed over into Libyan territorial waters, outside of the agreements made with other NGOs, who have been coordinating since May to cover a wider portion of the sea. Crossing into Libyan waters, however, may affect the routes of migrant boats in the long term: no one had ever gone that far. How will the smugglers respond? Will it act as a “pull factor”? Will the Libyan Coast Guard leave things in the hands of the international task forces? Regardless of reciprocal accusations, the only certainty is that the mandate of NGOs (saving lives) and that of European agencies (patrolling the borders) are now at odds: positive cooperation is not always possible. And thus, rescue efforts have suffered.

The other main reason for the continued deaths in the Mediterranean has a name: Libya. The country is still out of control, particularly in the coastal cities of Zuwara and Zawiya (the latter especially), ruled as it is by local lords who are profiting from human trafficking. They pack rubber dinghies, often made in China, with a minimum of 120 people, 3 times their maximum capacity. Until two years ago, 120 was the maximum for one boat. The dinghies sail in any weather, and the International Organization for Migration has reported that Libyan militias open fire on migrants who refuse to board. The dinghies are not likely to venture very far beyond Libyan territorial waters outside of the European missions’ reach. Often, then, the response comes from Libya’s Coast Guard, who fire at the boats – as reported by Reuters. Despite these blatant violations of international laws, Operation Sophia personnel will be training Libyan Coast Guard officers a month from now. Will the training help save the lives of those who take to the sea?

Even so, it would be wrong to believe that this deployment of men and assets is all in vain. The death rate in Mediterranean crossings has actually dropped since 2011. Overall, there were more than 18,400 deaths at sea between 2011 and 2016. In 2015, 1.86 per cent of migrants did not complete the journey from Libya to Italy. In 2016, as of November 28, that percentage had risen to 2.4.

Identification

But let us go back to October 3, 2013, the crucial moment in this story.

368 people died in the tragic shipwreck. In the aftermath, Italy launched an initiative that, in its own little way, has become a model one. Thanks to cooperation with several Italian universities, notably with Milan’s LABANOF (Laboratory of Forensic Anthropology and Odontology), led by forensic pathologist and anthropologist Cristina Cattaneo, identification efforts, rather than through DNA analysis, have advanced through social networks, SIM cards and personal items found on the bodies retrieved at sea. Together with interviews from survivors, these are the main clues that have been used to establish the identities of those who didn’t make it to our shores alive.

DNA analysis is expensive and requires the presence a blood relative, who may be very difficult to find, especially in the case of migrants from the Horn of Africa. The LABANOF has produced a portfolio of the items retrieved from the 368 bodies from October 3, 2013, a count that rose with 339 more victims after the second shipwreck on October 11, and the circa 700 bodies from that of April 18, 2015. This portfolio can be viewed by those looking for their relatives who can afford the trip to Rome. And these three shipwrecks are the reason why an agreement between the Ministry of the Interior and the universities on the identification of the bodies has been established.

According to the latest data released by the Extraordinary Commissioner, as of October 18, 551 casualties have been identified and given proper burial. And these costs are always covered by the cities, the only ones left to manage the crisis after the arrivals.

As Valentina Zagaria, an anthropologist who has been trying to give migrants a name on both sides of the Mediterranean since 2011, explains, at the beginning there was a large movement of ordinary people in Sicily who wanted to give the migrants a proper burial, and who were positively surprised that someone was taking an interest in the way they had organized tackling the problem.

That movement still exists though the public’s attention has shifted considerably over the last few years. Unfortunately, neither Italy nor Europe has the funds for an initiative of this kind. Prefect Vittorio Piscitelli would like to discuss it with his peers in Europe. So far, however, the idea has remained on paper. MEP Milena Santerini has promised to ask for a Council of Europe resolution in Strasbourg that would establish a European data bank of deceased and missing migrants, which in turn would allow access to data on DNA as well as other potentially useful information for post-mortem investigation. And then, who knows, 5 years from now, we might even be able to find all the names and stories behind the number 4,733.

[The article was edited to quote communications contained in documents released by Wikileaks]

Translation by Francesco Graziosi.