During the first half of 2017, more than 12,000 Nigerians reached Italy through Libya. By the end of 2016, there had been 27,000, a 48 per centincrease from the year before. They have been the most common nationality of central Mediterranean sea arrivals now since the summer of 2011, a time known as the so-called North African Emergency. Many are fleeing economic hardship and hope that Italy will provide them with an alternative. Others lived in areas where Boko Haram, the Nigerian terrorist organisation affiliated with ISIS, is strong. Moreover, the women are often victims of the slave trade, some even forced to sell themselves by their own families, and the overwhelming majority of them come from Edo State.

However, Nigerians have historically found it difficult to be granted asylum. According to data from the Ismu (Initiatives and Studies on Multiethnicity) Foundation, last year 71 per cent of them saw their asylum applications denied, and many of them appealed the decision. Their situation has become worse even in Germany: last February, the government led by Angela Merkel ordered the repatriation of 12,000 Nigerians who had not been granted political asylum despite the fact that many of them had lived in the country for years and become perfectly integrated.

The main cause for this spike in deportations has a name, and it is the European Commission Action Plan. Italy and Germany have been taken to task for the insufficient number of repatriations they carry out each year. As a result, both countries have stepped up their efforts, at the expense of what is perceived as the easiest target: the community of undocumented Nigerian migrants. But why? Because bilateral agreements are in place with Nigeria for fast-tracking deportations.

The Interior Ministry memo

On February 3, 2017, an informal summit of the European Council was held in Malta. Eu leaders want to shut down the Mediterranean route. They are thinking of the Libyan Coast Guard, which will be tasked with intercepting migrant boats before they exit Libya’s territorial waters. In exchange for Eu funds, the Coast Guard will comply. Eu member states, however, need to step up the rate of pushbacks. A few days earlier, on January 26, 2017, the Italian Ministry of the Interior had issued a memo — intercepted by the website stranieriinitalia.it — ordering the Cie (Centres for Identification and Expulsion) in Turin, Rome, Caltanissetta, and Brindisi to allocate a total 45 places for men and 50 for women, even through “early discharge” if necessary. The places were to be made available for Nigerian nationals. The header of the memo read: “auditions and charter flights”.

Again: why Nigerians? The answer is in the pages of our application for access to Frontex documents. The European agency for border control is the first funder of the increasingly frequent repatriation flights from Rome to Lagos. To leave these airplanes empty costs money. In order to fill them with passengers – wrote the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (Asgi) as soon as they learned about the January memo – the Ministry was willing to violate the principle of non-discrimination enshrined in Article 3 of the Constitution; in other words, to carry out deportations on the basis of ethnicity. “It is a major leap in repressive policies,” Asgi denounced back in February.

The Frontex flights

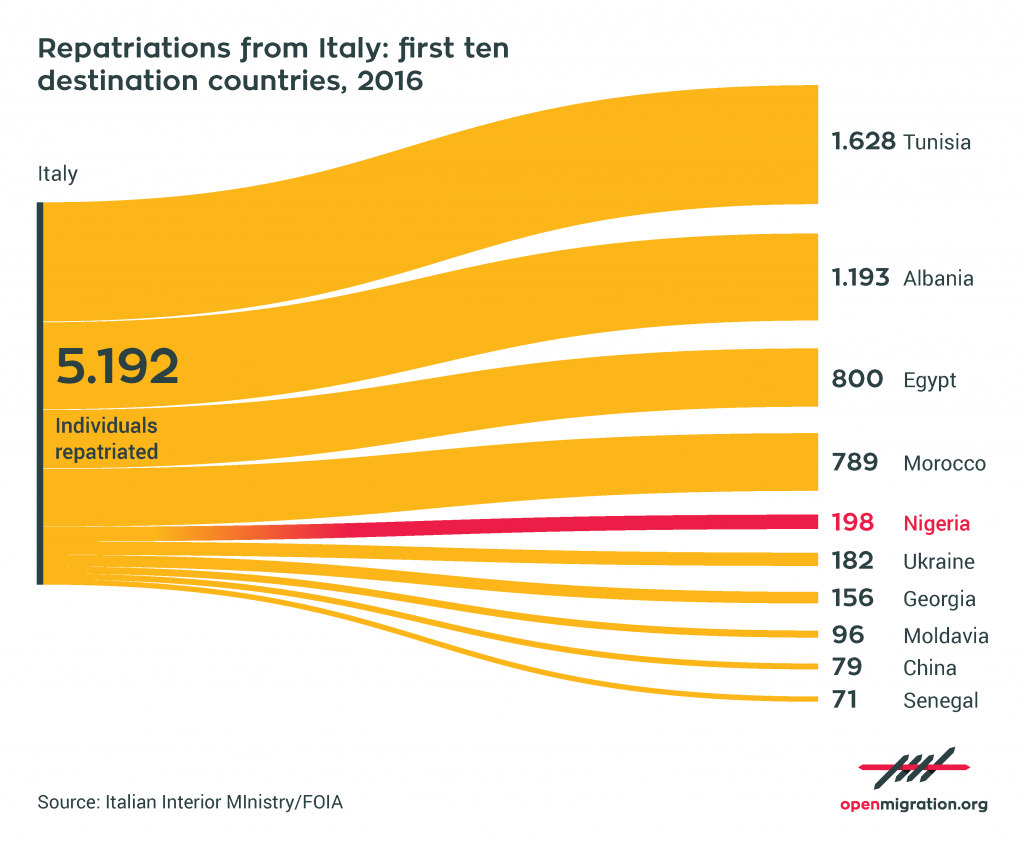

The Frontex data give us a clear picture of the increase in deportations to Africa’s most populous country. The Ministry of the Interior turned to the European agency to organise – and especially to co-fund – these expensive operations, as shown by the documents that we received from the Frontex Press Office.

The first documented repatriation flight to Nigeria departed on March 6, 2007. On board there were 40 Nigerian nationals from Italy (the organising member state) along with 30 more coming from Austria, Germany, Spain, and Romania. Since then, 48 aircraft have flown from Rome to Lagos, deporting a total of 1,394 Nigerians who had been targeted with expulsion orders.

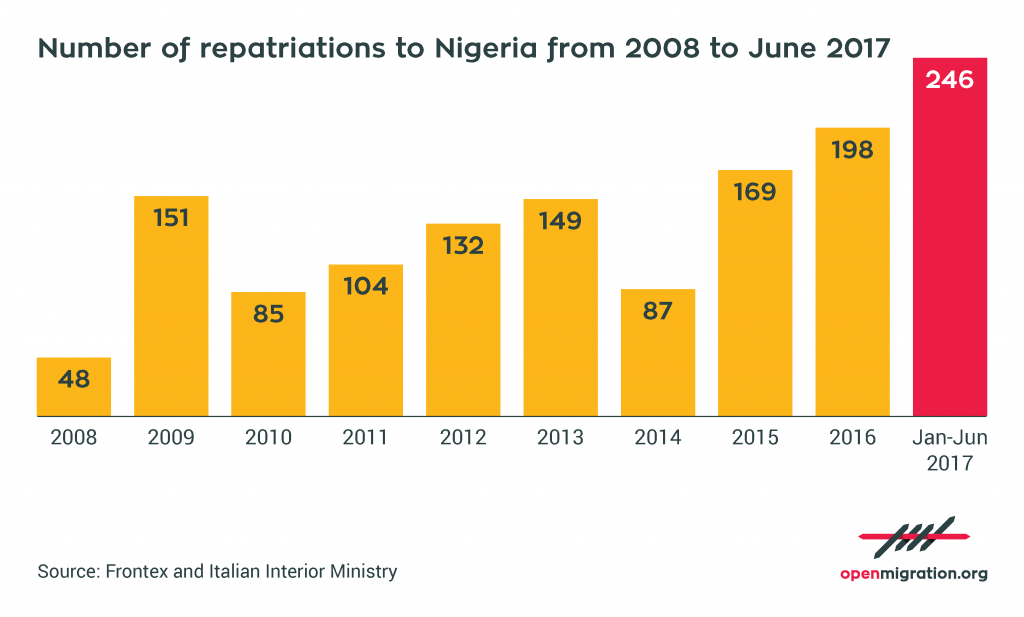

While the years between 2008 and 2015 saw no more than 5-6 operations per annum, forced deportations have since become much more frequent. Last year alone 7 repatriation flights left Italy for Nigeria. This year, the same number of deportations had already been reached by summer; therefore, it easy to predict that this will be a record year for deportations. Between January and late June, 246 Nigerians were deported from Italy on Frontex flights, compared to 198 throughout the whole of 2016. This escalation is in compliance with European Commission’s request to step up deportations, and, even though alternatives exist, it was backed by Minister Minniti.

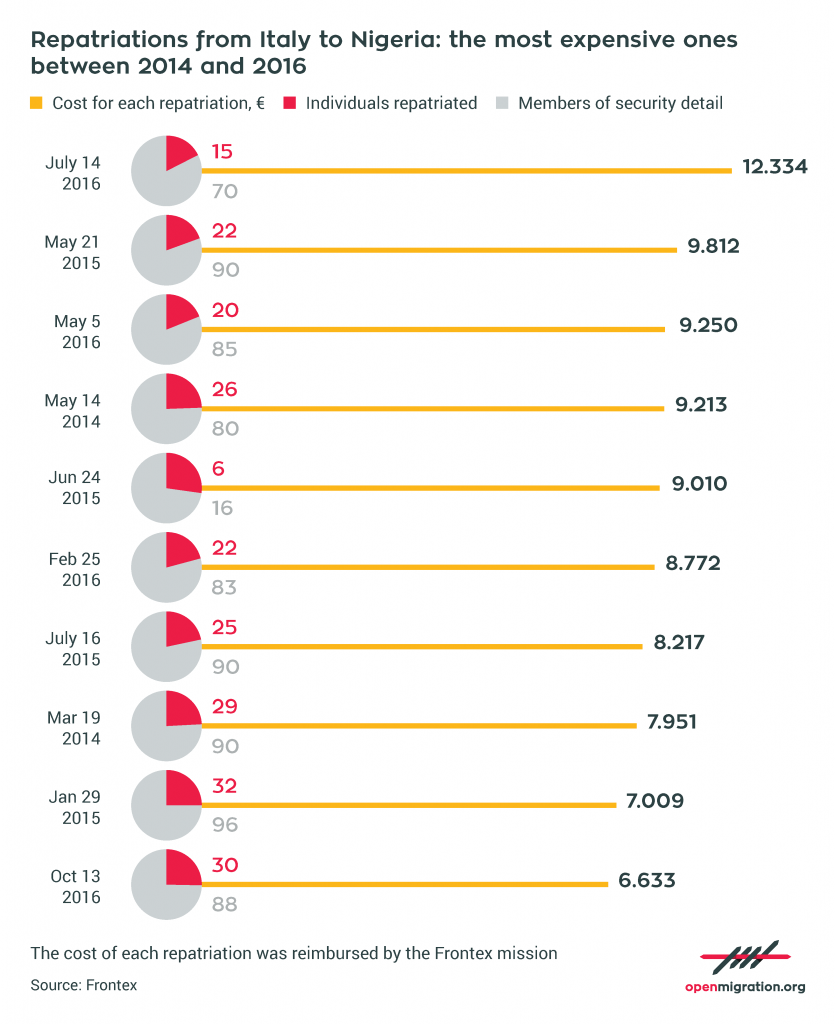

Despite political pressure, the number of the deported is still low compared to the number of arrivals, which means that the objective [maximing deportations] has not been met. In addition, the cost of these operations is often exorbitant. The expenses obviously vary according to several factors, including the itinerary, the countries involved, the designated carrier, and the number of security officers on board the aircraft (an average of three officers for every deportee). However, according to an Open Migration analysis of Frontex data, the average cost of an Italy-Nigeria operation may be estimated to exceed 210,000 Euros – that is, about 7,500 Euros per deportee on board.

Violations of human rights

“I remember the case of a woman who was unlawfully deported. When the judge issued a suspension order, she was successfully brought back from Nigeria. Most of the time, though, it is difficult to intervene to determine whether a repatriation is lawful or not,” says attorney Iacopo di Giovanni, who has worked with the legal clinic at Rome Tre University on several cases of deported Nigerians. “Without the right lawyer, it’s often very hard to even file an asylum request,” he adds.

Back in May, a group of volunteers working with asylum seekers at reception centres in Milan denounced a cyclically repeating situation. Before they are issued the papers to complete their asylum applications, migrants who say they come from Senegal, Nigeria, the Gambia, and the Ivory Coast are brought to police headquarters for further verification and, according to the volunteers, with no lawyers present. If they state that they came to Italy “seeking employment”, they are denied the right to apply for asylum on the grounds that they are economic migrants. Consequently, they are not even allowed to sleep in centres for asylum seekers, and automatically become undocumented migrants. In late May, Open Migration spoke with volunteers who described at least 12 such cases. These incidents were followed by a note addressed to the prefectures and police headquarters signed by Asgi, Naga, and other groups; as early as April 2016, Naga, Avvocati per Niente, and Asgi wrote to the prefect and the police commissioner in Milan — with the Unhcr and the Interior Minister in copy — denouncing the “utterly unlawful” practice which had been adopted by the police desks.

If stereotyping on the basis of ethnicity is in violation of international law, what is the reason why so many Nigerian migrants are facing the risk of expulsion? Nigerian criminal organisations exist in Italy, and there are fears that the new arrivals may join these “fraternities”. The main organisations based here are known as Eiye and Black Axe, criminal networks that resemble the gangs of the Camorra with little hierarchy and a very fluid style of management. Their chief operations include trafficking in women and drug dealing. Sometimes, as in the case of the market area in Palermo, they are on the streets selling drugs which were previously dealt by Italian crime gangs and are part of a system. While stereotyping on the basis of ethnicity runs contrary to international law, it is a fact that the context of the Nigerian diaspora in Italy has made law enforcement agencies and authorities deeply suspicious. And this is why Nigerians are still at the top of the list for deportations.

Translation by Francesco Graziosi, proof-reading by Alex Booth.

Cover image: Nigerian refugee women – via World Bank Photo Collection (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).