In July 2013 the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service launched a series of advertisements to stop refugees from seeking protection in Australia.

The campaign aimed to educate and inform asylum seekers, including unaccompanied minors, in source countries about the futility of investing in people smugglers, the perils of the trip, and the hardline policies that awaited them if they did reach Australian shores.

The campaign was predominantly conducted online and featured a video message that lasted just over a minute with the commander of Operation Sovereign Borders, Lieutenant General Angus Campbell, standing next to a sign declaring “NO WAY” in bold, red letters over an ominous background that showed a small rickety boat on a churning sea. “The message is simple: if you come to Australia illegally by boat, there is no way you will ever make Australia home,” he says.

This campaign has been criticized as one of the harshest border policies in the world by human rights groups for its perceived bigotry and disregard for human life. Highlighting how hundreds have died attempting to journey to Australia from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq and Iran on old and dangerous boats, the non-profit Refugee Action Coalition Sydney denounced the Australian government’s allocation of $60.3 million to extend Operation Resolute, which includes Operation Sovereign Borders, as prioritizing a policy of “stopping boats, not saving lives.”

Three years later, on July 28, the Italian government launched a media campaign on television, radio and social media platforms to dissuade African migrants from attempting the perilous journey across the Mediterranean Sea. With the declared aim of avoiding deaths (read: saving lives), the Aware Migrants – campaign targets would-be migrants between the ages of 18 and 35 in 15 different countries in North and West Africa to make “them” aware of the potential risks involved in the attempt to reach Europe.

The 1.5 million-euro campaign is the latest of several attempts by Italy to convince fewer refugees to make the journey, with others including a deportation and relocation programme. And this is not the first European fear-mongering campaign. Although this campaign focuses on reducing loss of life by informing migrants of the dangers of irregular routes, smuggling or trafficking, in its attempt to use communication to discourage irregular migration Italy seems to be following a precedent set by Hungary and Denmark.

Indeed, to limit the flow of refugees, in 2015 the Hungarian government—in addition to the 112 mile-long fences along its border with Serbia—used advertising campaigns to actively dissuade refugees from entering the country. These advertisements were published in several Lebanese and Jordanian newspapers and warned refugees not to attempt to enter Hungary illegally. The full-page advertisements in Arabic and English informed readers that refugees caught entering the country illegally could face imprisonment.

A few months later, the Danish government published a similar advertisement in major newspapers in Lebanon warning migrants not to come to the prosperous Nordic country, highlighting the fact that those who were rejected for asylum would be deported from the country. It spent 30,000 euros on an advertising campaign that emphasized the stringent regulations and constraints that await migrants.

Probably in order not to be accused of heightening anti-immigrant rhetoric (like in the Hungarian and Danish cases), Italy’s Minister of the Interior decided to adopt a more veiled warning to migrants. And there is no doubt that IOM’s involvement, as one of the main refugee rights groups that has called for better treatment of those choosing to make the journey, represents a strong humanitarian aspect of the project.

One must not forget that Angelino Alfano—who launched the campaign stressing that “economic migrants comprised 60 percent of last year’s 154,000 arrivals” and noting that Italy and the rest of the EU “must speed up the repatriation of migrants with no legal residency rights, otherwise the bloc’s migration policies will collapse”—is the Interior Minister of the government led by Matteo Renzi, Italy’s Prime Minister who has perfectly integrated the humanitarian discourse of assistance and hospitality within the on-going language of migration governance.

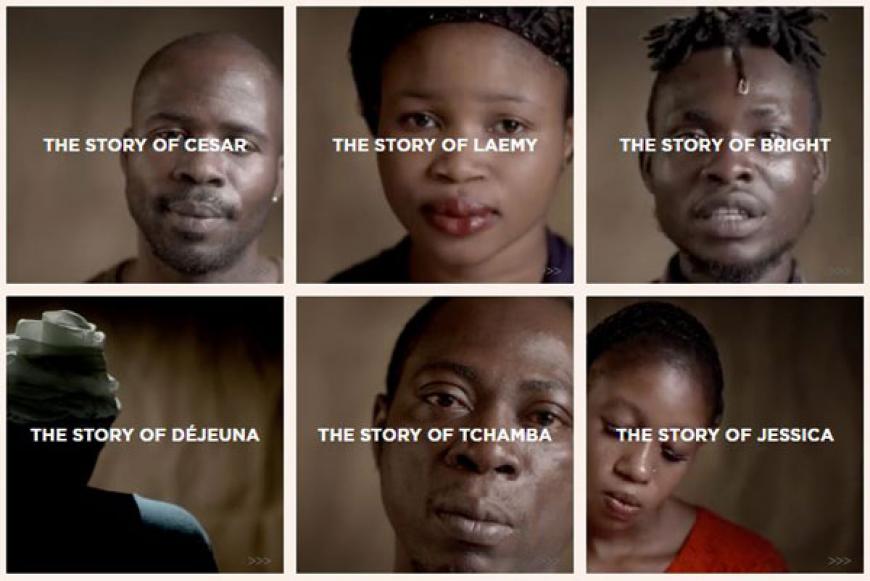

The Aware Migrants campaign (Photo: IOM)

Over the last two years, Matteo Renzi has repeatedly insisted that Italy and all of Europe have a humanitarian duty to protect people making the journey.

At the same time, Renzi, like most European leaders, is keen to show that he is taking steps to differentiate between refugees who are fleeing war, and those who are seeking a better life and economic opportunities.

But what is the evidence of the impact and effectiveness of these campaigns in deterring vulnerable people in search of a better life from leaving their source countries?

As a research report prepared in July 2015 for the UK government by the University of Birmingham shows, there is extremely little evidence on whether they are effective, and anecdotal evidence suggests that they have limited, if any, effect on migrants’ decisions to leave.

Despite the methodological problems with trying to collect data from irregular migrants—who may be difficult to contact and fear speaking to the authorities, or may misrepresent their motivations for travelling in order to try and rationalise their decision—several evaluations conducted in a range of countries from Senegal to India, from the western Balkans to Kenya and Zimbabwe, have concluded that “it is hard to show a chain of causality between a specific programme and reduced migration.”

Although the Italian campaign seems to adopt some factors which, according to UNHCR, may improve the effectiveness of these campaigns—like targeting a specific group of migrants, including real-life testimonies from returned migrants, and using celebrities to convey the message, like the Malian artist Rokia Traoré—, the absence of information about legal opportunities and the lack of trust in the information received are among the main reasons that its effect on migration behaviour is limited. As the GSDRC report argues, “awareness campaigns may be irrelevant to prospective migrants who consider the attempt at changing their life to justify the risks involved.”

When potential migrants perceive that information campaigns are driven by vested interests (from governments and international organisations), they are likely to dismiss them as propaganda. They usually consider themselves better informed about the risks than those who are producing the campaigns, especially when information is disseminated through mass media and official channels.

Furthermore, as a great part of most of the literature argues, other factors play a much stronger role in migrant decision-making: risk information does not seem to change decisions to migrate, as the perceived opportunities abroad continue to outweigh the risks, and migrants continue to rely on reports from trusted social networks about conditions in destination countries.

The literature is fairly clear that the causes of irregular migration are not a lack of information about its dangers, as information campaigns assume, but the unchanged conditions of poverty, inequality, conflict and lack of economic opportunities at home, factors which information interventions do not address. However, these factors are beyond the reach of policymakers.

But to come back to European governments’ attempts to look at Australia’s “stop the boats” policy as one that might “solve” Europe’s migrant crisis: I think that Australia’s immigration policies and the public debate around immigration in Australia cannot provide a useful roadmap for Europe. Among other reasons, primarily because the Australian policy at no point has taken into account the need to protect those people who are fleeing wars or poverty; furthermore, because Australia’s tough stance on asylum-seeker vessels appears to be illusory for it hasn’t stopped the boats, it has merely displaced the flow to other nations, like Indonesia or Malaysia.

In stark opposition to these ineffective attempts to deter migrants through communication campaigns, we should keep in mind that the boats crossing “our sea” (Mare Nostrum) have to be considered “our” problem (or, why not? our opportunity). If we really wish to save lives and to come up with better responses to meet the tremendous needs people face risking the dangerous journey, it would probably be better for EU governments to turn the core question from “How can we stop migrants?” to “Why are people fleeing?” and “How can we provide people with the ability to apply for visas/asylum lawfully”?

HEADER PHOTO: Open Borders