From the Albanian invasion to the Romanian crime emergency

Do you remember the Albanian invasion? In 1991 at least twenty-thousand men, women and children arrived in the port of Bari from Albania aboard a single ship called the Vlora. The people of the city spontaneously organized a human chain of solidarity. The mayor at the time was Enrico Dalfino, a Christian Democrat and professor of administrative law at the local university. Dalfino represented the kind, sympathetic face of Bari. His idea was to have the Department of Civil Protection take care of all those lives in limbo, which had been provisionally amassed inside the Stadio delle Vittorie. The government, on the other hand, wanted to have them deported them straight away. The face of this hard-line policy was President Francesco Cossiga, who went on record saying: “[Dalfino] is an idiot, and the Interior Minister should remove him from office.” For years the Albanian crime emergency was talked about as something that would endanger the safety of an otherwise spotlessly clean, honest and immaculate country. The truth is, in the Eighties every woman in Bari was mugged on average a dozen times a year by young, unmistakably local, street criminals. As the Vlora approached the shores of Apulia, the Mafia was busy slaughtering innocents and the Tangentopoli scandal was just breaking. There were other, much more pressing criminal issues to tackle.

After the fall of the first Republic, migratory flows shifted. The following years saw a significant increase in the number of Romanian nationals on Italian soil. Thieves, robbers, murderers and rapists: this is how they were characterised. Nearly every member of Parliament called for preventive measures against Romanians in the wake of the brutal murder of Giovanna Reggiani in 2007. A decree-law was immediately adopted, which introduced rules for the expulsion of EU citizens for reasons of public security, against all logic and even EU regulations themselves. Antonio Di Pietro, leader of the Italy of Values (then a government party), declared that Italy could not become “the urinal of Europe.” Less than a decade later, however, fearmongers from both the left and the right are no longer raising the spectre of Romanian crime. Their ethnic and criminal priorities have shifted as well.

Every migratory wave, especially when it is not managed in a rational manner, inevitably brings the risk of illegal activities. Particularly so when people are forced to live outside the law. In the early years of every national migratory wave, failure to carry out integration policies leads to an increase in the number of foreign nationals being incarcerated. Towards the end of the last decade, it was unclear whether being Romanian was a nationality or an aggravating circumstance, as one satirical cartoon famously observed. Only after a community of foreigners has consolidated its presence by integrating, can the statistical data on crime and incarceration rates be interpreted properly. As everyone who has studied crime prevention policies can attest, the makeup of prison populations is determined not only by the number of crimes committed and current regulations, but also by the empirical culture of judges and attorneys, which is in turn strongly affected by messages from the world of politics as well as the mass media.

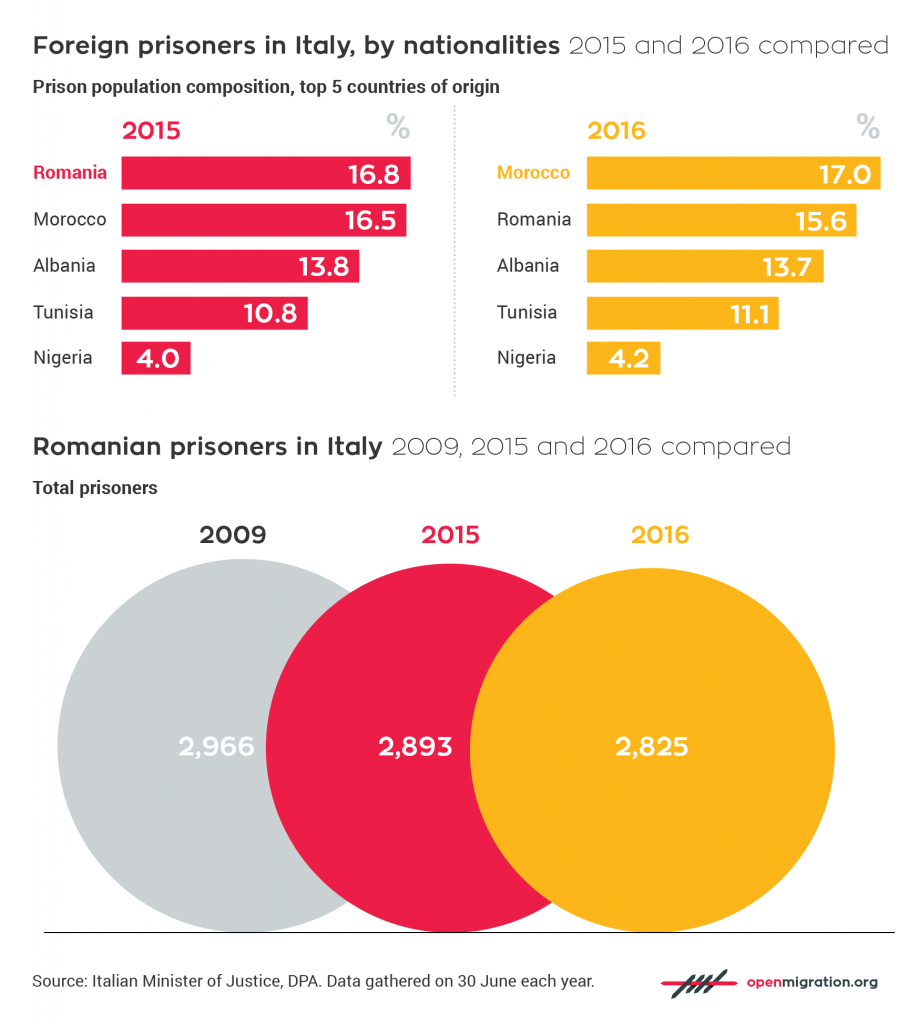

Beginning in 2009, and for several years thereafter, Romanians were one of the largest groups among foreign inmates. This is no longer the case today: we are witnessing a decrease in their numbers inside Italian prisons.

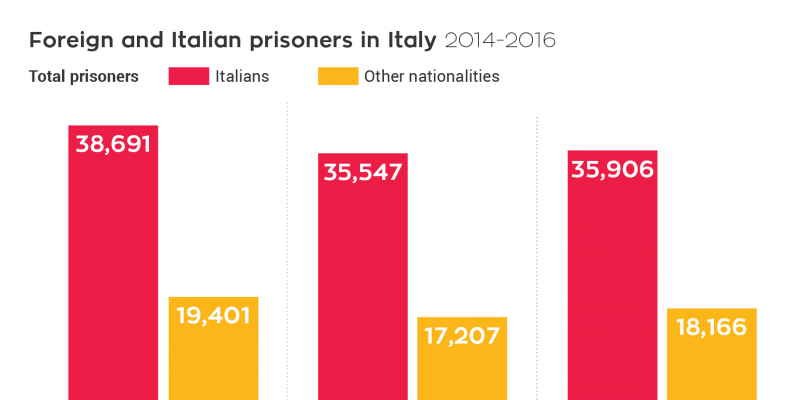

As of June 30, 2016, there were 18,166 foreign nationals incarcerated in Italian prisons, accounting for 33.5 per cent of the total prison population (54,072). The previous year saw 17,207 foreign inmates making up 32.5 per cent of the total, which was 52,754 at the time. Over the course of a year, the total prison population increased by 1,318 units. Since June 30, 2015, the population of foreign inmates has increased by 959 units, which represent 72.7 per cent of the total increase in the number of inmates over the last year. The number of foreign inmates has increased threefold compared to their Italian counterparts. The highest recorded percent of foreign inmates was 37 per cent, in 2009-2010.

The need for crime prevention initiatives based on actual data rather than prejudice

It is not easy to determine the cause of the increase in the population of foreign inmates, given that there have been no changes in the law, nor in the rate of crimes committed in Italy by either locals or foreign nationals. What has certainly contributed to it, however, is the general atmosphere of distrust towards foreigners, even from institutions, which is reflected in the actions of law enforcement officers and in arrest and detention procedures.

A closer look at the percentage of foreign nationals in the total prison population helps us to understand the link between the public perception of a lack of safety and repressive responses by the authorities and law enforcement; the former affects the latter regardless of the nature of the offences and the number of crimes that are actually committed.

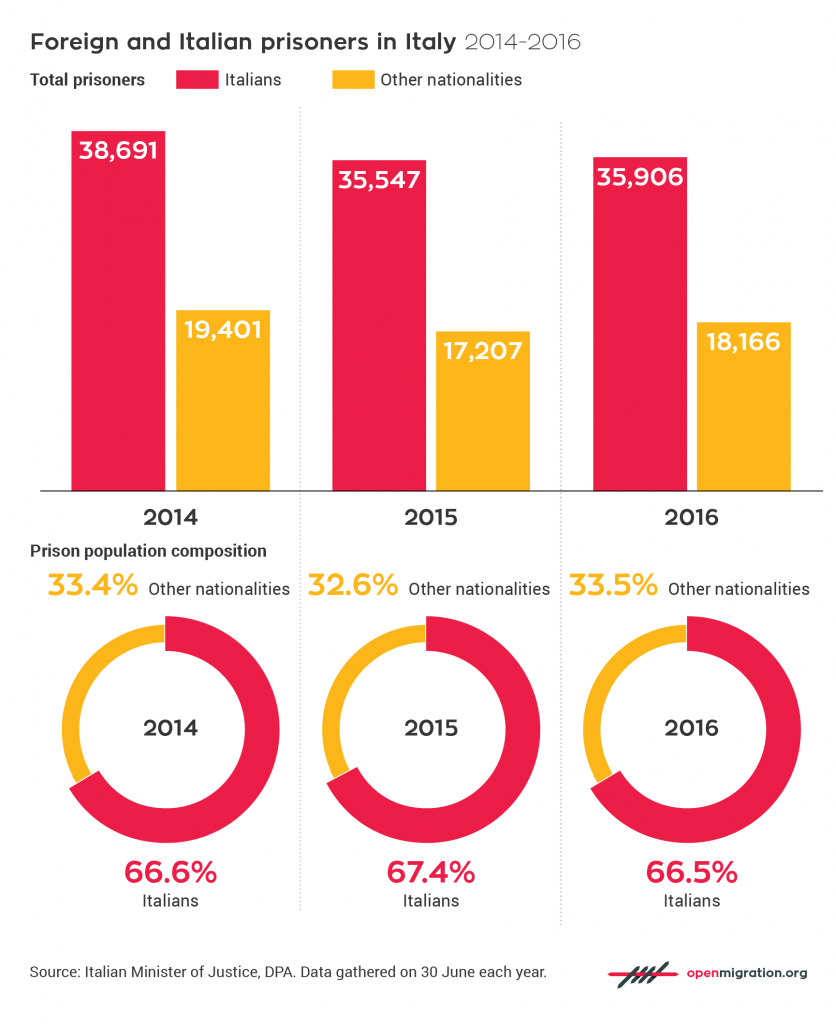

The situation of Romanians is clearly emblematic. The percentage of Romanian inmates has decreased significantly over the last few years. Today the public’s concerns are directed elsewhere. What has happened, then, is that while there has been an increase in both the number and the percentage of Italians and foreign nationals being incarcerated, the opposite is true of Romanians. Prejudice against Romanians has decreased, and consequently they no longer account for such a large percentage of the total inmate population, a record that is now held by Moroccan nationals.

There were 4,125 Romanian inmates in Italian prisons in late 2013, but this is hardly a significant figure given the general decrease in the inmate population following the reforms implemented by the Italian government after the European Court of Human Rights ruled against Italy in the Torreggiani case (January 8, 2013). On the other hand, comparisons with the data from 2009 are extremely useful. 2009 saw the culmination of the so-called “Romanian crime emergency”, with a total of 2,966 Romanians incarcerated. This number decreased during the following seven years, despite an increase in Italy’s Romanian population. The alarm was therefore unwarranted, and it also produced xenophobic reactions.

An analysis of the Romanian inmate population by offense gives us an indication of the actual criminal threat they pose.

There are currently 35 Romanians incarcerated for activities related to Mafia-style organized crime. The total number of people incarcerated for this type of crime is 7,015. Romanians account for 5.2 per cent of the total prison population, limited to the 193 Italian ones, but for only 0.49 per cent of those charged with, or convicted of, affiliation with a crime syndicate. The same percentage applies to Romanians incarcerated for violating drug laws: 91 out of a total of 18,941. Thus it seems safe to say that Romanians are not drug traffickers.

Despite the many journalistic and political stereotypes about Romanians being muggers and rapists, the actual percentage of Romanians being detained in Italy for crimes against property (6.2 per cent of the total prison population and not much higher than the global average, which is 5.2 per cent) and against persons (6.5 per cent of the total) is rather low. On the other hand, Romanians do have a high rate of detention for sexual exploitation: they account for 31 per cent of the total prison population for this type of offence. Every crime prevention initiative should be based on actual data, not prejudice.

Translation by Francesco Graziosi.