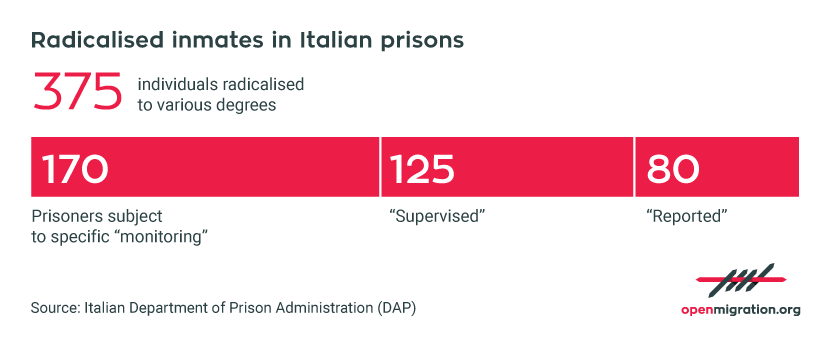

On the 11 th of January, in response to a parliamentary question, the Italian Minister for Justice disclosed the official data collected by the Department of Prison Administration (DAP). These data reveal that Italian prisons accommodate 170 inmates subject to a specific “monitoring”, plus 80 “supervised” and 125 “reported” ones, according to the exact definitions adopted by penitentiary institutions.

Minister Andrea Orlando also remarked that the Italian prison system currently houses 45 inmates charged with crimes related to international terrorism. They are in the so-called “High Security 2” wings, in Benevento, Brindisi, Lecce, Nuoro, Sassari, Tolmezzo, Turin, Rome Rebibbia and Rossano. 27 out of 45 are held in Sardinia.

Words matter: what is the definition of radicalised prisoner?

There are four categories of prisoners that are somewhat associated with violent radicalisation: terrorists, monitored, supervised and reported inmates. While the definition of terrorists is quite clear, as they have been accused or taken into custody for a specific kind of crime, the composition of the remaining three categories of ‘radicalised’ prisoners is not as obvious.

We can plausibly assume that indicators which assess the degree of ‘violent radicalisation’ have been created and implemented, but the first questions arise here. What are these indicators, and of which kind are they? Were they pinpointed after a research? Is there any tangible evidence supporting their effectiveness, or did they result from suspicion? Are they based on specific criminological theories or just experience? Were such criteria formulated according to statistical analyses or to empirical and sometimes aesthetic approaches?

In order to save lives, one may answer, linguistic details can be put aside. Maybe they can, if this does not imply an even higher danger for the lives at stake. Because we could pay for any injustice and misjudgement with a leap in radicalisation.

The work of the DAP in monitoring what happens into prisons is useful for everyone’s safety. But it is important not to let suspicion define the ‘correctional’ path of prisoners. Labelling as ‘radicalised’ an inmate who is not, would make his life in prison much harder. For this reason, errors based on suspicion must be avoided, as they could induce violent reactions even in people who do not have such inclination.

The justice and prison system makes an unforgivable mistake every time it is responsible for victimisation processes.

Radicalisation: is Islam the real problem?

We will now focus on the potential victims of radicalisation in Italian prisons.

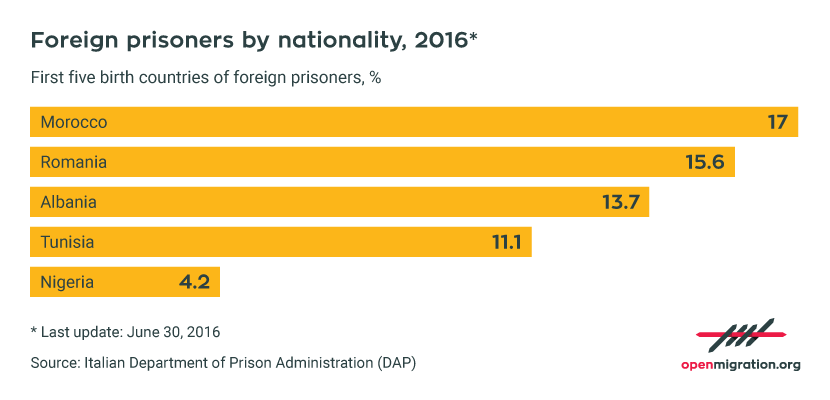

To this day, these penitentiaries accommodate about 55 thousand inmates, and 18 thousand of them are foreigners.

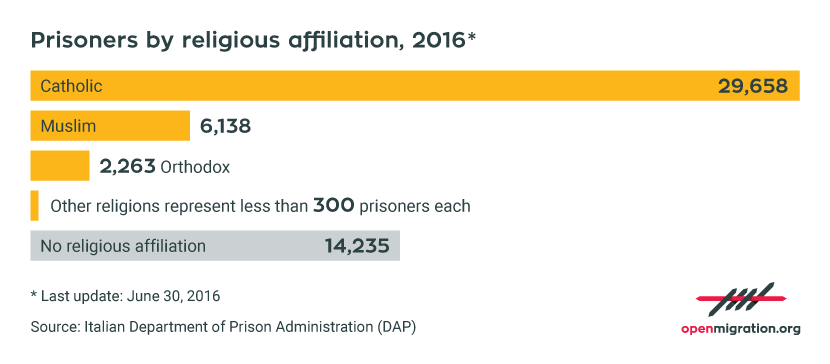

According to surveys conducted a few months ago, prisoners who openly profess their faith in Islam are 6,138, but almost 15 thousand inmates chose not to declare their religious affiliation. It is easy to imagine that among them there are many Muslims who do not want to be kept under surveillance. Under the rule of law, everyone is free not to declare if they do or do not believe, and in which god. Religious surveys are borderline prying in such an obviously and incontestably intimate subject. Nobody should receive a special prison treatment, either more or less rigid, because of their religious beliefs or their refusal to disclose them.

Considering these numbers, why is the risk of violent ‘radicalisation’ so high in Italian prisons?

The first reason has to do with logistics. A prison is a closed space, where people spend uncountable hours together talking about the same things, day after day. Many of these institutions do not offer any kind of activity, so idling is their only option. This is the best breeding ground to lead someone ‘astray’. The victimisation and radicalisation process is easier and its probability of success increases if the prisoner is ill-treated, isolated, forced into starvation, without any rehabilitation chance.

Promoting rights to fight against radicalisation

In order to oppose radicalisation, prison rules and practices should be reformed. Freedom of belief and foreign prisoners’ rights should be considered a priority. There is a law on this matter, waiting for the Senate’s vote. The Chamber of Deputies has already approved it. It is included in a much wider proposal about justice, regarding many subjects. It should be separated and approved immediately.

The Department of Prison Administration was right when they decided to entrust an Imam from Ucoii (Italian Union of Islamic Communities) with the training of prison officers. It is a good start against radicalisation.

Learning about different cultures and religions helps understanding them, defeating prejudice, distinguishing between believers and radicalised inmates, between radicalised and violently radicalised ones. Further steps are within our reach. And so are social and work policies in favour of individual deradicalisation programs.

It is a hard work. Certainly harder and less tempting than summary segregation, labelling or expulsion. But it will prove more useful for security purposes. And it is undoubtedly more respectful of everyone’s dignity.

Translation by Lucrezia De Carolis. Proofreading by Alexander Booth.

Header picture by Sara Jo (CC BY ND 2.0)