The larger context within which migration flows emerge matters. Most major migrations of the last two centuries, and often even earlier, can be shown to start at some point –they have beginnings, they are not simply there from the start. My focus here is on a particular set of new migrations that have emerged over the last one or two years; such new migrations are often far smaller than ongoing older migrations.

New migrations have long been of interest to me in that they help us understand why a given flow starts and hence tell us something about a larger context. This is the migrant as indicator of a change in the area where they come from. Once a flow is marked by chain migration, it takes far less to explain that flow. Most of my work on migration has long focused on that larger context within which a new flow takes off, rather than routinized flows that have become chain migrations (e.g. 1988; 1999; 2014).

The loss of habitat

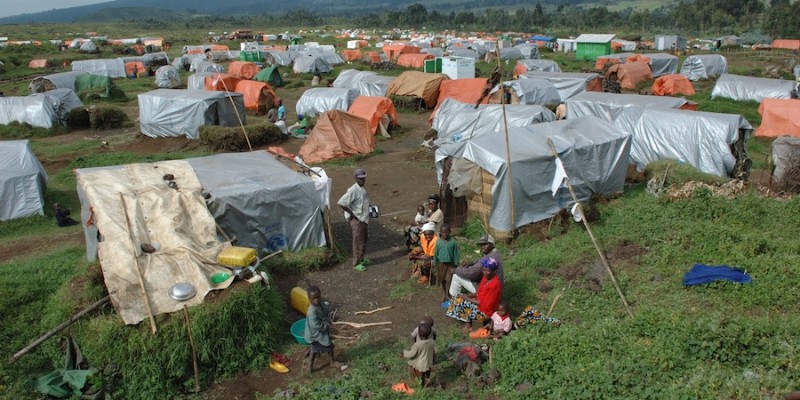

I see today’s migrations as marking a new historical phase. They signal that there is a major combination of forces that is producing a massive loss of habitat in more and more areas of the world. It is difficult for me to simply think about these as migrants and refugees. Where they are coming from is part of the story and it should be put up front.

There is a mix of escalating negative conditions leading to a massive loss of habitat across the world. It is this loss of habitat that has remained insufficiently addressed in the current discussion and analysis of the new migrations. War is a major factor in this loss of habitat, but there are many others and they will eventually generate outflows of people that will, once again, take the experts by surprise. We want to put war alongside an array of other factors generating a loss of habitat for at least 2 billion rural and semi-rural peoples across the world.

These include prominently climate change (desertification, rising waters, dying land due to heat); massive acquisitions of land by foreign governments and firms to meet demand back home, the building of new, often private, “cities” and office parks; the sharp expansion in mining to meet the demand for new components from the electronics industry; the accelerating poisoning of land and ground water due to the toxicity of current plantation agriculture, mining, manufacturing and more. Beyond their effect on rural populations, urbanized areas have long had unhealthy toxic spaces and conditions. To this we can now add emergent scarcities, notably of water, which are now reaching alarming levels in a growing number of urbanized spaces.

Language is insufficient

It is this mix of diverse conditions, with armed conflict a very direct element, that leads me to argue that the language of immigration and refugees is insufficient to capture this emergent history. In the case of war, we must also take note of two features often left out of what is (understandably) the major focus on death, maimimg and physical destruction. One concerns the toxicities and other destructions of habitat that war brings with it, often rendering life almost impossible even once a war is over. The second, critical in today’s world, is that war today is asymmetric, and these are wars with no end.

When we bring the loss of habitat into the picture, we should at least consider the possibility that the traditional concepts and policies concerning the immigrant and the refugee, are not enough today to address the current migration phase. “Immigrant” and “refugee” are still powerful concepts, but they were generated in a different spatio-historical context. Many elements of that context continue to be operative and many of the policies to govern migrants and refugees are effective, or at least helpful.

War as the factor of displacement. But not only

Our question is more specific and it does not preclude the continuation of older trends well captured by those traditional concepts. We ask, are we seeing an emergent set of flows of desperate people for which we need to address a much larger and intractable set of conditions –what we will refer to as the loss of habitat.

The general policy area that addresses the fact of growing displacement of people is today confined to war as the factor of displacement. But displacement takes many forms: losing one’s land due to corporate grabs that are not fully lawful; having to leave one’s land because of toxic elements produced by the local mine; the expansion of asymmetric war, and more.

In short, the current migration phase should be a wake up call: existing policy is not prepared to address new types of conditions producing massive displacements and neither is it prepared to deal with the consequences of such displacements. It will require developing global networks of policy makers that address the specific instantiations taken by generic conditions in different types of regions or countries, as well as recognizing the need for new types of cross-border policy domains.

The new refugee

At the heart of my argument here is an emphasis on the need for the governance of a range of very different types of actors generating displacement than those addressed by the humanitarian system. This makes for a more realistic approach to massive flows of displaced people in today’s key policies where acceptance depends on some sort of validity of the displaced person –with war the key valid cause.

To put the decision of declaring a valid claim of displacement onto the displaced individuals themselves works for war but not for the type of displacements generated by the expansion of mines, land and water grabs, the poisoning of water and land due to toxics and pesticides, and more. Those displaced by mines and land grabs should be recognized as victims, and the blame should go to the mines and the land-grabbers. We need a broader conceptual map to trace and establish who or what caused the displacement. And this means that there can be massive displacements even when there is no war.