In partnership with:

Rather than trying to stop refugees in transit to Europe, the States should create safe and legal access channels for asylum-seekers. The international resettlement programme supervised by UNHCR and the humanitarian corridor initiative established in Italy by the FCEI (Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy) are both steps in the right direction.

The latest tragedy at sea is only a few days old, but every day EUNAVforMed personnel are intercepting boats adrift in the Mediterranean loaded with dozens of migrants who are desperate enough to risk their lives during the crossing. While the flow cannot be stopped – not even by erecting physical barriers along borders – both States and NGOs can try to create an alternate access route to their territories. The international resettlement programme supervised by UNHCR and the humanitarian corridor initiative established in Italy are both steps in the right direction.

In the Projected Global Resettlement Needs 2017 report, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees submitted more than 1,000,000 cases for resettlement.

Resettlement: what is it?

Before embarking on an in-depth analysis of the report, a preliminary clarification on the meaning of resettlement [ho inserito il link corrispondente in inglese, sul sito unhcr.org, NdT] is in order. Resettlement is an international protection tool designed for refugees who cannot return to their countries, even if they have sought protection in another State, where their integration or their safety is at risk. These people can be transferred to another State that has voluntarily agreed to the resettlement programme and is providing a certain number of places.

Resettlement is a safe and regulated immigration channel: on the one hand, it can reduce the illegal traffic of people fleeing war zones; on the other hand, the States themselves determine how many refugees they will admit and check whether the refugees meet the requirements for legal access to their territory.

Some numbers

Based on the report, in 2015 submissions for resettlement went up from 103,000 in 2014. UNHCR expects to file 143,000 submissions in 2016 and 170,000 the following year: according to projections, Syrian refugees will account for about 40 per cent of the total. Already last year, on average, two out of five submissions were Syrians.

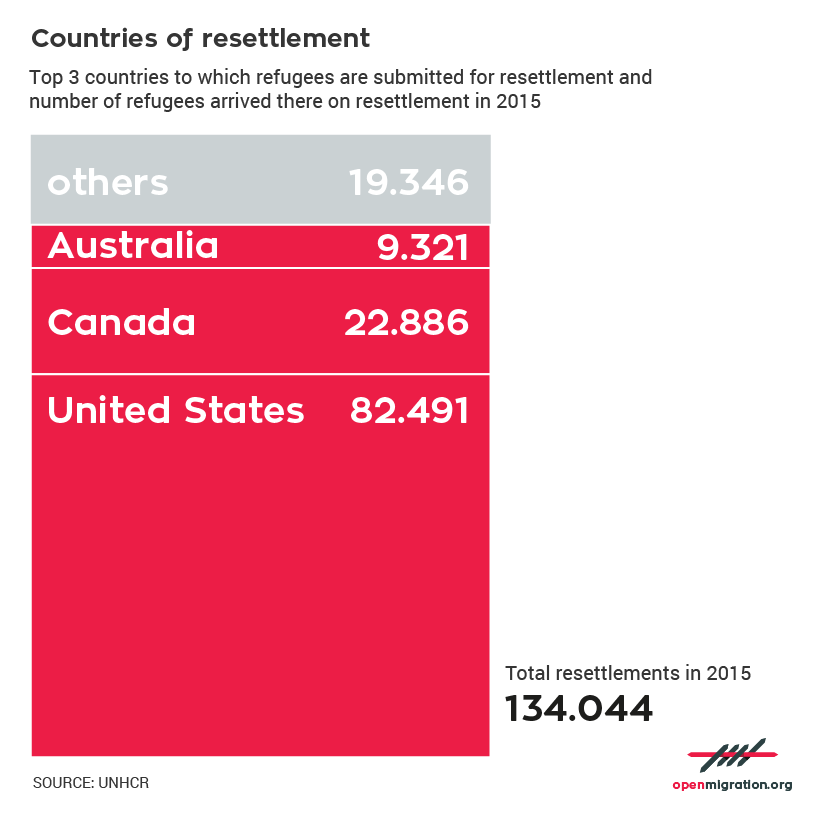

The resettlement programme is not, however, confined to Europe and recent migrations from the Middle East; it involves States and NGOs across the world. This is shown clearly by the distribution of submissions in 2015: the United States registered 82,491 submissions, followed by Canada (22,886), Australia (9,321), Norway and the United Kingdom.

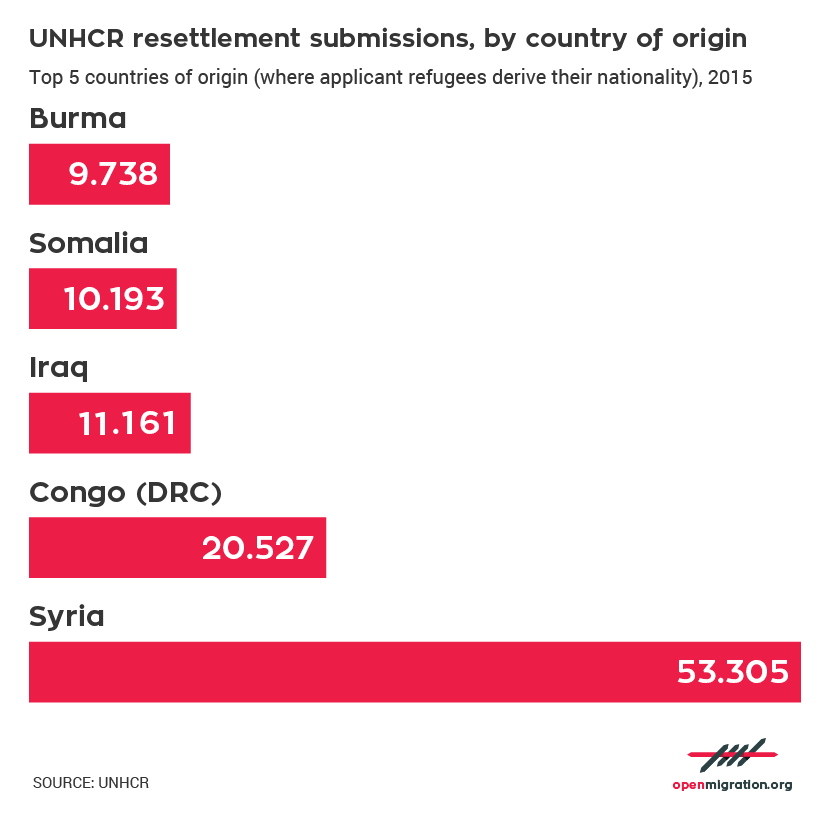

The countries of origins for refugees submitted for resettlement in 2015 reflected the main on-going conflicts: Syria had the record (53,305), followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo (20,527) and Iraq (11,161). Somalia had 10,193 submissions and Myanmar had 9,738.

UNHCR Resettlement submissioin by country of origin

The country of origin often does not match the nationality: many submissions are for refugees who have already been granted asylum abroad, but in refugee camps where legal protections and safety are not guaranteed. The top four countries of asylum are Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and Kenya, receiving tens of thousands of refugees from the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa. Turkey has one of the most volatile situations, having gone from 1 to 2.5 million Syrian refugees over the last year (plus 250,000 from other countries, such as Iraq), and having submitted over 18,000 refugees for resettlement globally.

The MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region had the most resettlement submissions globally (53,331), a 13 per cent increase from 2014. This extraordinary growth is largely due to the humanitarian crisis in Syria (in 2015, nearly 49,000 submissions were Syrian citizens) and has led some countries (USA, Canada, Australia and UK) to offer more places and to implement an expedited resettlement process for Syrian refugees. In the face of such an emergency, with no immediate resolution in sight, UNHCR is advocating for resettlement for at least 10 per cent of the Syrian refugee population (about 4.8 million people) by the end of 2018.

An increase in the number of submissions was also registered in Africa (from 35,079 in 2014 to 38,870 one year later), where the vast majority of applicants have been living in protracted refugee situations for over 20 years. Conversely, submissions from Asia and the Pacific region (21,620) and the Americas (1,390) decreased, due to the resolution of conflicts or improvements in the condition of refugees.

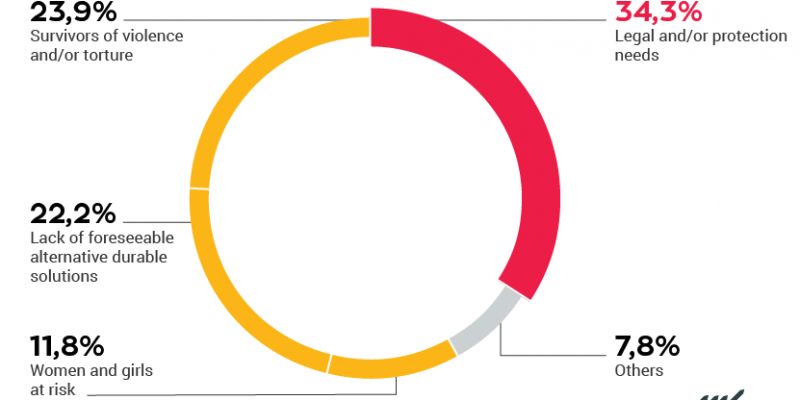

As for the categories, Legal and Physical Protection Needs constituted about one third (34,3%) of all the cases submitted for resettlement in 2014 and 2015. Survivors of Violence and/or Torture was the second largest category in 2015 at 23.9 per cent, followed by the category Lack of Foreseeable Alternative Durable Solution at 22.2 per cent and Women and Girls at Risk at 11.8 per cent.

Resettlement in Europe

According to the Projected Global Resettlement Needs 2017 report, the number of resettlement submissions from Europe increased from 16,392 in 2014 to 18,883 in 2015, mainly due to the rise in the number of submissions made from Turkey. Additionally, due to the conflict in Ukraine, over 3,000,000 refugees have sought protection in neighbouring countries. Despite Europe being essentially at peace, national asylum systems in certain Eastern European countries lack the capacity to ensure effective protection, exposing asylum-seekers to xenophobic and racist acts that threaten their physical security.

As is well known, in recent years Europe has seen a dramatic increase in migration: ISIS and the conflicts in Africa and the Middle East have led to the creation of huge makeshift refugee camps from Kenya to Turkey, and driven over a million people to cross the sea in the desperate attempt to reach the coasts of Italy and Greece. Unsafe boats and the greed of human traffickers have caused thousands of deaths: 3,775 in 2015 and already 1,261 this year.

Following these shocking tragedies, Germany opened its doors to Syrian refugees, while the European Commission recommended an EU resettlement scheme for 20,000 refugees from Africa and the Middle East in May 2015. In July of the same year, the European Council agreed to the resettlement of 22,504 to be distributed proportionally across 32 States (28 EU members plus Liechtenstein, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) according to each country’s GDP and population size. Italy has pledged to take in 1,989 refugees (constituting 9.94 per cent of the total) by December 2017.

According to the UNHCR data available to Carta di Roma, 419 people have arrived in Italy through the resettlement scheme so far.

Humanitarian corridors in Italy

The resettlement programme provides refugees with legal access to a country where they will be safe, and that will grant them civil and social rights. It is still, however, a pathway available to only a few thousand people. The greatest difficulty lies in the selection of beneficiaries among the hundreds living in refugee camps, as well as in persuading the States to offer their financial and logistical cooperation.

Therefore, in Italy, response to the refugee crisis also came from civil society organizations – particularly the FCEI (Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy) and the Community of Sant’Egidio. While looking at the complexity of European regulations, they saw the opportunity to create an additional legal access channel for especially vulnerable asylum-seekers. The pilot initiative for humanitarian corridors was the result of a Memorandum of Understanding signed with the Ministries of the Interior and of Foreign Affairs, with the NGOs envisaging the arrival of 1,000 refugees over two years. So far, the beneficiaries have come from Lebanon, with more to follow from Morocco and Ethiopia, in order to intercept the great migratory flows created by war in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, before the refugees take to the sea.)

The initiative was lauded by Pope Francis himself: the pontiff took 12 asylum-seekers to Rome after a trip to Lesbos, with the Community of Sant’Egidio providing the first welcome.

Currently, 279 people (mostly Syrian refugees) have arrived in Italy through these corridors. As in the case of the UNHCR programme, this initiative provides a safe pathway for refugees, in line with governmental security standards; the potential beneficiaries are pre-selected by the NGOs, then vetted by the Ministry of the Interior and finally granted a humanitarian limited territorial validity visa.

The pilot initiative was launched at no cost to the State: the NGOs cover travelling and first reception expenses. So far the initiative has raised 1 million euros, largely from the Eight per thousand tax devolved to the Waldensian Church.

A model to follow

The humanitarian corridor project is based on a model of solidarity that can be replicated in other States, as was explained by Vittorio Zucconi, Secretary General of the Community of Sant’Egidio, during a recent meeting with the UN ambassadors. The Republic of San Marino has also joined the programme and now, says Zucconi, “we are receiving positive signals from Poland as well,” while “the Italian Episcopal Conference is negotiating with the government.”

The importance of this initiative has been recognized by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Paolo Gentiloni (“Humanitarian corridors are a message to Europe to remind everyone that raising walls is not the solution”), and more recently by his deputy, Mario Giro (“More involvement on the part of civil society is crucial”). Even the President of the Italian Republic, Sergio Mattarella, has praised the initiative: “The creation of humanitarian corridors places Italy at the forefront of solidarity efforts, and it represents a moment of actual fulfillment of its constitutional principles.”

One thousand people over two years is not a large number. However, as the motto of the campaign says, a few small drops can change the sea.