Luca Ricolfi writes on Il Sole 24 Ore (7 September 2015):

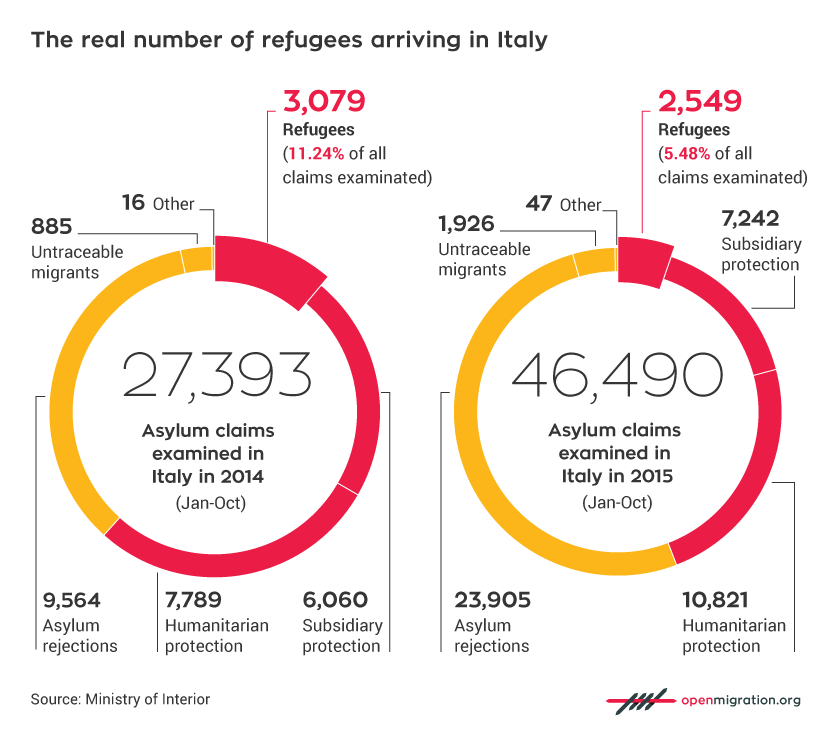

In the past three years, more than 300,000 people arrived from the sea but only less than half of these subjects applied for asylum. Out of 100 asylum requests, only 10 actually end up being given refugee status; the other 90 are either rejected or accepted through others form of protection (the so-called “subsidiary” and “humanitarian” models of protection). It can thus be concluded that the majority of people who arrive in Italy either do not present request of asylum or they present it and have it rejected on grounds of not being entitled to it. According to official data, it can be evaluated that only the 6% of people arriving in Italy gets protection as refugees after having presented an asylum request.

The analysis

“Refugee” is a term which gets used with two different meanings. Following a strict application of the term, a refugee is someone who gets recognized as such, according to the 1951 Geneva Convention.

In a broader interpretation, though, “refugee” is instead commonly used to refer to all people entitled to protection, either because they are exposed to persecution or because they would incur in serious danger were they to return to the countries they fled, or because of other humanitarian reasons. Hence the ambiguity that Ricolfi’s article seems to be willingly playing on.

The Territorial Commissions in charge of assessing asylum rights can actually give three different kinds of permit:

- Residence permits on grounds of asylum are granted to refugees (technically, persons fleeing from persecution on grounds of race, religion, nationality, social group or political beliefs). This permit lasts five years and it can then be either renewed or converted in a permit for work reasons. It grants a wide variety of rights, such as the right to being reunited with family members, the right to travel and to work, just like Italian citizens.

- Residence permits on grounds of subsidiary protection basically give the same rights by the same conditions. This type of permit is indeed usually granted when the status of refugee cannot be acknowledged, but there are nevertheless reasons to believe that, if the applicant returns to the country he fled, he would be exposed to risk of serious harm; in other words, it represents the approval of a request of international protection.

- Residence permits on grounds of humanitarian protection are granted to those who are not fit neither for asylum nor subsidiary protection, but are nevertheless entitled to protection for humanitarian reasons. This type of permit only lasts three years and gives less rights.

If it is correct to say that in the past few years only 1 request of asylum out of 10 ended up with the acknowledgement of the status of refugee (a number which is now reaching an even lower record, according to 2015 data). At the same time, though, the number of requests for subsidiary or humanitarian protection that get approved is significantly bigger (61% in 2013, 60% in 2014, 45% in the first two months of 2015).

While it is true that the majority of people who arrive in Italy do not apply for asylum here, it is not correct to explicitly argue (or subtly imply) that this group of people is made exclusively of economic (and thus irregular) migrants.

In 2014, about 170,000 people arrived in Italy from the Mediterranean sea and 65,000 of them seeked asylum in the country. This number can be easily explained by considering that only a small percentage of the two biggest groups – the Syrians (42,000 arrivals) and the Eritreans (with 34,000 arrivals) – chose to seek asylum in the country (respectively, 505 Syrians and 480 Eritreans); the overwhelming majority of them preferred to request protection in other European countries.

The same has been happening in 2015: between January and February, 143,000 persons arrived from the sea and only 69,000 of them filed a request for asylum. It is also to note that (among those people) only 475 were Eritreans, despite this being by far the national group with the highest number of arrivals through the Mediterranean route.

Who can deny that the gap between the number of arrivals Italy and the number of asylum seeker can be explained by the fact that many prefer to request it in other European countries?

One could easily argue that this could be the case by looking at the rates of request approvals in other European countries: 98% for Syrians, 87% for Eritreans and 59% for Somali (the latter being the third national group with the highest number of arrivals in Italy in 2015).

According to the rates of approval of requests, it can be estimated that about 59% (Unhcr) of the persons arriving in Italy through the Mediterranean are entitled either to the status of refugee or to international or humanitarian protection.

To sum it up: during 2015, only 48 out of 100 people arrived in Italy seeked asylum in the country. Amongst those, 22 will receive some form of protection. It can also be estimated that 59 more of them will receive protection in the European Union.

Our evaluation

Ricolfi’s approach to data – just as the approach of those using similar arguments – is not incorrect as much as it is tendentious, because it implies that only the status of refugee (that is, the type of permit with the lowest rates of approval) can be considered as proper protection.

Moreover, by ignoring the phenomenon of people who arrive in Italy but then travel to other European countries – he ends up portraying all the others as irregular immigrants.