When we started this journey, the hub on Via Sammartini had taken in 107,000 migrants over the course of three years. That number has now risen to 114,000 — 21,500 of whom are children. Here, among the young and the little ones, reflecting on the future is inevitable. At the hub’s medical practice, a pediatrician volunteers an hour a day, but it’s not enough, and Dr Boustani, naturally, treats children too. He told me he must have cured at least 700 by now. And so our exploration ends where it all began: with the drawings by children in the space operated by Save the Children and L’Albero della Vita. And on the day I meet the operators, the hub is suddenly overflowing with Kurdish families – small children are everywhere.

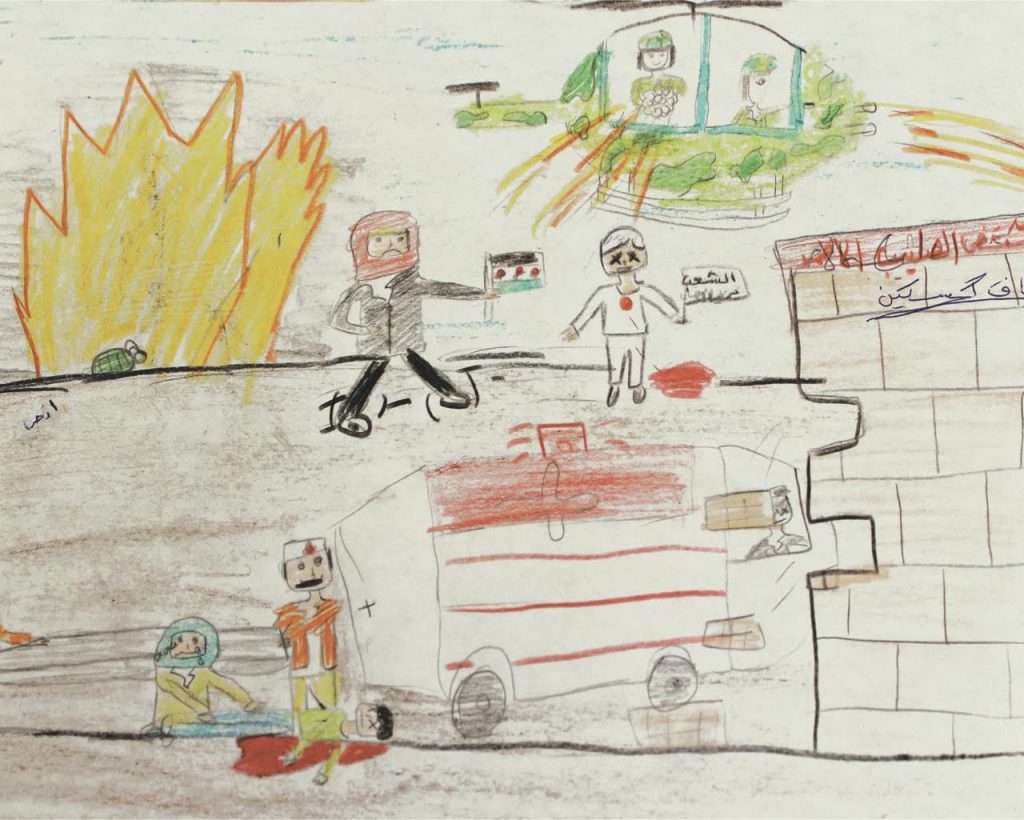

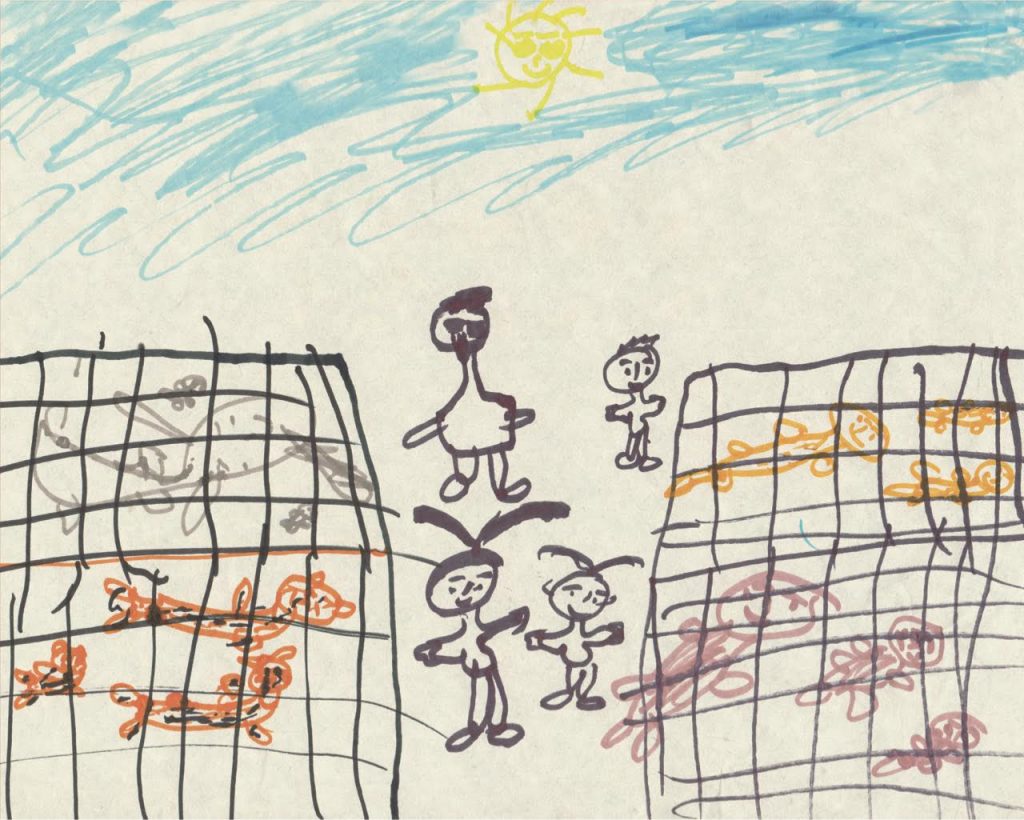

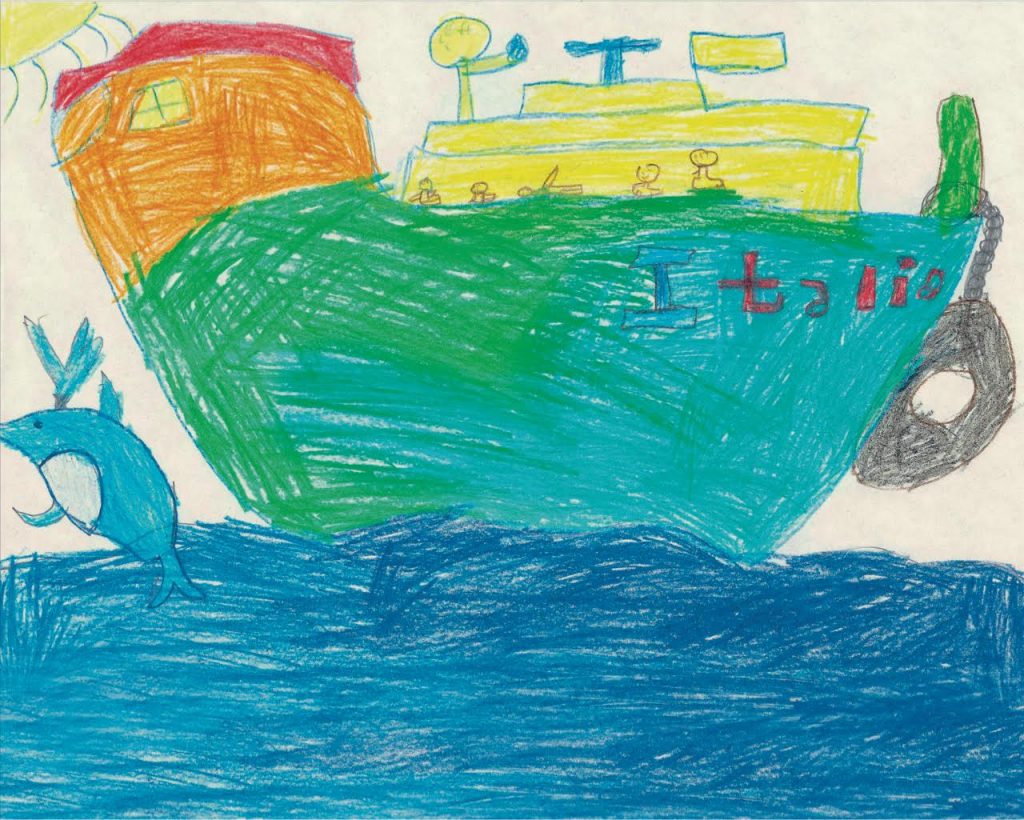

The drawings feature a lot of blue water, and some sharks. Francesco Salvatore from L’Albero della Vita, who is in charge of the Minors Emergency Programme, shows me one depicting a dolphin, the overcrowded rubber boats, and a bulky Italian ship taking migrants on board; however, there are also helicopters, armoured vehicles, and rubble. “Our task is to create a safe space where children can stop by, adapt at their own pace and play while we also take some of the burden off of their parents’ shoulders. A place with a certain normalcy, with few, but clear rules, some planned activities, snack breaks, but also a space where kids can play freely on their own – and that’s where we often notice the release of pent-up aggression. Rituals help – we celebrate the arrival of every new child, with greetings and goodbyes.” Among the tools at hand, there are also wordless, visual fairy tales, re-enactments of the children’s journeys. Even among the adults, I have noticed, a sense of epic is being created, of having achieved something heroic and unforgettable. “It is very reassuring for a child to learn that many other children before him have faced a similar journey, and many more will follow,” Francesco explains. “It makes the fear more manageable, less foreign, less extraordinary, and it lets them know that the worst is already behind them.”

Lina, 8 years old: “My school in Damascus was bombed and I was afraid. Everyone was screaming and there was smoke everywhere… I could not see anything. I managed to escape but some of my friends didn’t”.

The hub operators have witnessed a tremendous capacity for recovery in the children. Albero della Vita has collaborated with the Università Cattolica on a study examining the resilience of migrant children in transit. The children have strong memories of their homes, of traditional holidays, of the last thing they did before leaving: “I miss my cat that I left in Syria after giving him some yoghurt,” one of the drawings Francesco is showing me says. At the hub, as well as at other centres in Milan, like the one in Via Mambretti, children have found sanctuary, and pre-teens have found some lost inspiration. “Two years ago, we had a little girl who hadn’t spoken in 11 days. Her father was sick with worry. Here at the hub she started talking again. Among the pre-teens there are some who were born in refugee camps and never got an education, while others haven’t been to school in two years because of the war, and they ask the operators for textbooks, something that caught us by surprise.”

Some of them, mostly boys, are unaccompanied minors. Many are sent off by families that cannot afford to travel; others have lost their parents. Sometimes it is difficult to even know how old they really are: “For their safety, they are advised to say that they are older or younger than they really are.” According to UNHCR data, between January and July of this year, 59 per cent of Egyptians arriving by sea were minors. If adult Egyptians have no hope of getting asylum, the new Italian regulations grant asylum to all unaccompanied minors, even when they are not seeking it. The real tragedy is that of all the unaccompanied minors who have gone missing. “Many of them run away from the facilities that are meant to protect them, they want to keep travelling and it’s very hard to stop them,” Francesco says. “That’s why we teach them about their rights and the major dangers of travelling: drugs, exploitation and prostitution.” As of July 31 this year, 5,315 minors were missing from the reception centres surveyed by the ministry.

At a table in a corner of the cavernous warehouse over cups of powdered chocolate milk, Francesco tells me that making the hub what it is today has not been easy at all: “Without the city’s oversight, it would have been impossible to make such a complex network last,” he says. “After the first wave of emotional solidarity, it took a huge effort to harmonize resources and create a system of volunteers, and their work is patchy by definition. The reason the hub has worked is that everyone here knows what their role is, and they know exactly what to do.”

Taha, 8 years old: “I am afraid of bombs”

“Politically the idea is to put yourself out there and take responsibility,” says Pierfrancesco Majorino, who has been overseeing things since day one. “We can’t just assume that the prefectures alone, or that the third sector alone, will take care of things.” Milan’s Municipal Councillor for Social Policy, first with Mayor Pisapia and now with Mayor Sala, Majorino also remembers where it all began: “a meeting of volunteers at a sandwich bar” under the freezing colonnade of Central Station. One remarkable intuition of his was to pool the resources in Milan for refugees, homeless people and impoverished Italian families, not treating them as separate issues and sometimes, like on Via Mambretti, even putting them all under the same roof. “No one was taking care of refugees, not the prefectures,” he tells me. “You need to consider that only 30 per cent of these people are what we call prefettizi,” that is, people who were identified upon arrival and sent up north on buses, or who were seeking asylum. “Everyone else,” Majorino explains “have come here on their own, and they become asylum seekers once they are processed. We need to be ready for this.”

“In the absence of a real national policy on immigration – just look at the Baobab debacle in Rome – this is just a starting point for us, a way to look forward. The next frontier, what we need to get better at, is making asylum seekers members of our society: language training, integration, employment, housing. It is crucial that we get them to interact with their environment, and that we protect their health, especially their mental health; protecting the more vulnerable among the vulnerable. The network that we have managed to create is exciting, but there is still so much untapped potential. We need the feminist network to mobilize in support of foreign women who have been raped, we need psychologists. Recently, we created our own national conference on immigration to share models and solutions with other cities that have asked us for help. You need to think that 20 per cent of cities are taking in migrants while 80 per cent are not; subtract from that the really small towns and the disadvantaged ones, and you’ve got about 50 per cent that could potentially take in migrants. Now, even if half of these are hard-core Northern League areas or right-wing and thus anti-immigrant, that still leaves around 25 per cent that could help; and Milan needs to be able to share this effort with the greater metropolitan area.”

Looking down Via Sammartini from the hub, one can see the Pirelli Tower – the seat of the Regional Council of Lombardy, currently governed by a Northern League majority that vetoed the housing of immigrants in the former Expo base camp. “Well, since they didn’t want to give us the Expo facilities for the refugees, we will at least request that it be assigned to Italian families in need,” Majorino comments wryly. “The Region also recently voted against us using the former hospital in Garbagnate. In this case we will go forward as planned, since the city owns the building and the region’s vote isn’t binding. The next step is hosting refugees in private homes. We have been working with five pilot hosting families and we are planning on bringing that number up to 52.”

In October, the neo-fascist group Casa Pound protested the housing of 300 asylum seekers at the Montello Barracks on Via Caracciolo. The neighbourhood quickly mobilized, and a few days later there was a full-scale block party to welcome the asylum seekers — associations, a lot of migrants, food and music. I ask Majorino if he would have expected such a response. “Well, it was so big even the Washington Post covered it; it was really unique. The chemistry in that neighbourhood is special, too. I’m not expecting the same kind of response elsewhere, and that’s fine. No one bothers the migrants on Via Sammartini, but some of the residents walk up to me on the street and inevitably have complaints, as do the residents of Quarto Oggiaro, where 5-600 migrants have been housed for four years.”

The future is full of uncertainties that reception alone cannot dispel. Operator Reema and Dr Boustani wonder what will happen to their homeland of Syria, and think an attempt is being made to change the distribution of the population across the country. Dr Boustani is only optimistic because “Syria has suffered all manner of occupation and destruction; but we will emerge once again. From the Romans to the French – it will end when the arms trade stops conducting its dirty games, and people will have died in vain, but Syria will get back on its feet just like it’s always done.” Meanwhile, Reema fears she will end up like her Palestinian grandmother, who kept the keys to the family house all her life without ever being able to return. She also reminds me of the vast economic gulf that drives people to risk everything to get to Europe in the first place. “The other day I sent 50 euros to my cousin in Syria. It was enough to cover her trip to the city, the paperwork required to start her medical practice, the hotel and the trip back home.”

Alberto Sinigallia from Project Arca thinks that the challenge for the coming years will be that “once Syrian families are reunited in northern Europe and the demand for the workforce has been met, as in Norway, the doors were once again shut. And at that point the refugees have no future.” Of all those seeking asylum in Italy, less than half are likely to receive it. According to the latest Amnesty International report on migrants in Italy, 42 per cent of asylum applications were granted in 2015, and as of October 7 this year only 38 per cent. A few thousand were granted asylum on appeal following an initially negative decision. Everyone else was not granted asylum. Without money or papers, unable to seek asylum elsewhere or to return home, stranded in the streets of European cities, they became vulnerable to all kinds of exploitation.

In the meantime, Omar, pending his own asylum request, has no more dreams: “The only thing I want is to work. And then get married. And because I’ve now left Africa behind for good, maybe I’ll marry a European girl. I will only go back to Africa as a tourist.” Sinigallia comments: “I don’t know, I have seen many places that have extreme poverty, including the slums in Calcutta, but I went to the Ivory Coast a few months ago – a place that is regarded as Africa’s Switzerland – and I was shocked by the level of poverty in Abidjian. That’s when it hit me. It is a poverty so deep that nobody, no matter how much talent or willpower they possess, can ever hope of getting out of. There is no upward mobility; you can only survive at an animalistic level, day after day, for your entire life. It is astonishing that more people don’t try to leave.”

Yasser, 15 anni, “I was really, really afraid of dying – but I also experienced hope, and bravery”.

Upon leaving, I think of the hundreds of people who made themselves available to help the migrants, who have let the experience change them. As Francesco puts it, “the moment they are welcomed, accepted, the moment their exhaustion is relieved, this truly changes the meaning of these people’s journey.” I think of all those who didn’t survive the crossing. The Afghans still travelling along the officially closed Balkan route; the Syrians waiting, crammed along the border of Jordan and in the camps of Greece, where snow is now beginning to fall; all the Sudanese who have stopped arriving since Italy struck a forced deportation deal with the Sudan. I think of Libya aflame, where some still hope to pack the refugees into camps far away from European eyes. And now I feel the beat of the hub, the rugged heart of a city that knew how to answer the call of history.

Read Parts 1, 2 and 3 of our report.

All drawings are taken from “In viaggio verso il futuro – storie di bambini siriani in transito” [Travelling towards the future: tales of Syrian children in transit], an initiative by Albero della Vita and the Università Cattolica.