The gym Espace Jeunes du Moulin in Grande-Synthe, on the outskirts of Dunkirk, starts bubbling with activity after sunset. Volunteers relentlessly answer questions from the people gathered in the sports centre, queues for the toilets grow longer, and Naza tries to get ready.

She was told that tonight, if they move fast, they may be lucky enough to find a lift towards England. That is why she is putting all her belongings into a little blue backpack, causing uproar among the children who have noticed her. Some of them burst into tears and run to their parents because Naza is seven years old, and the things she is taking with her are toys that belong to everyone.

The women of Grande-Synthe

Naza’s mother, Birwa, draws the girls of the Women’s Centre aside and speaks in a low voice: “I need legal advice.” The Italian police took her fingerprints one year ago when her family arrived from Iraqi Kurdistan, but they do not want to apply for asylum in Italy. According to the Dublin Regulation, should Birwa be caught crossing the border illegally, she will be sent back to the country where she was first identified.

She is four months pregnant, and she would like to give birth to her child in the United Kingdom so that “staying there becomes easier.” She has to leave. But the fear of setting out on a new journey, especially in her condition, makes her hesitate. And in any event, the final decision lies with her husband.

Frances Timberlake is a volunteer for the Women’s Centre in Grande-Synthe, and is working on a project about the experience of migration from a woman’s point of view. “Adult women who live here represent a minority and they almost never travel on their own, but always with their husbands and children,” she explains. “On the contrary, most of those arriving in Calais are alone and much more vulnerable to violence and human trafficking.”

Frances believes that this difference depends on the country of origin and the different paths that these women have followed. Strangely enough, Grande-Synthe mainly receives Kurdish migrants from Iraqi Kurdistan. In the past, there were fights with people from other nationalities in Calais, and this generated separate groups. “It is very likely that there is a smuggler working in that area that sends them here all together, because apparently they do not know each other,” adds Sabine, who is helping Frances with the translations for her project.

In some desperate cases, volunteers find temporary accommodation for migrants who are forced to live in Puythouck Park. Nurses and midwives from Gynécologie Sans Frontières (Gynsf) give assistance to men, too, but homeless women are their main focus. “Our emergency number is available 24/7 for particularly vulnerable women: victims of sexual assault, mothers with young children, or the very young themselves,” they say. “They can call us; we pick them up and take them to a safe apartment where they can stay, two or three days at most. The exact location of this hideaway is kept secret to avoid any consequences.”

The endless wait before crossing

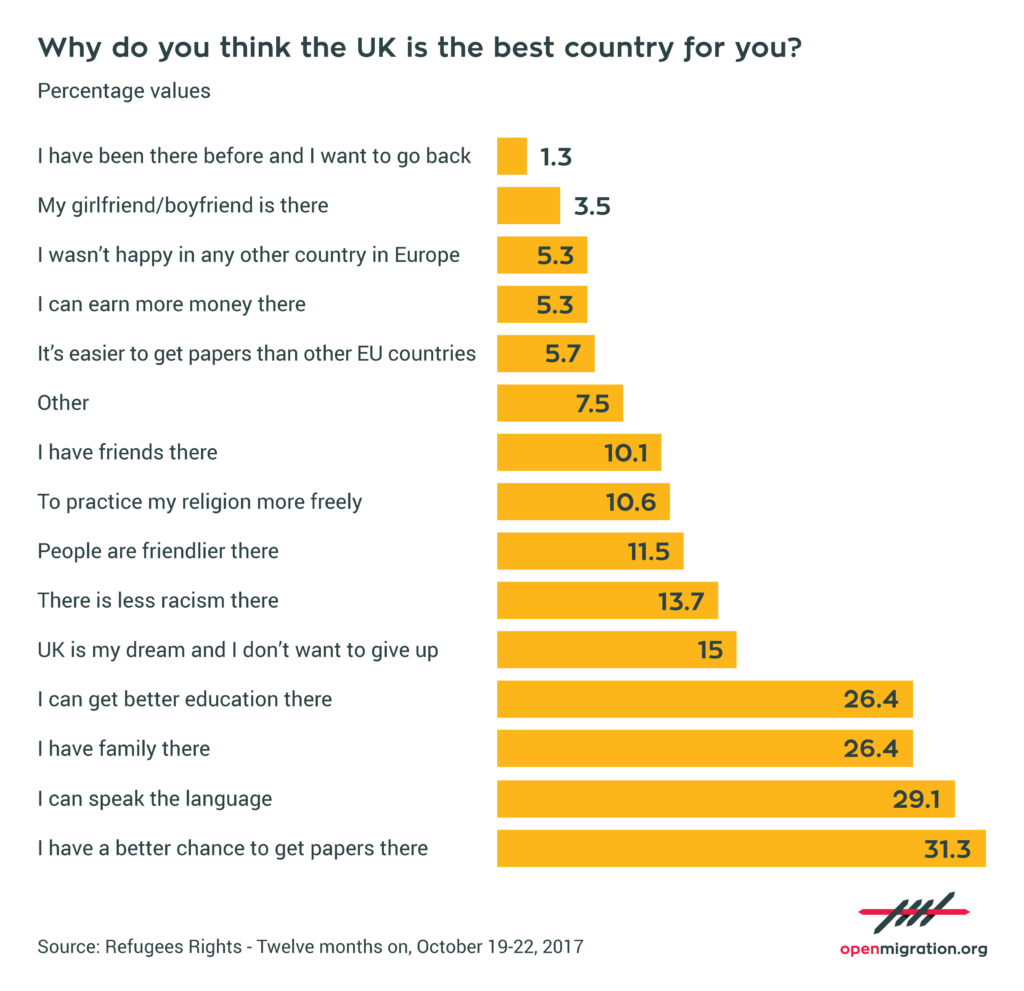

Establishing how many people live in northern France after the closure of the Calais Jungle is almost impossible, except for the Centres d’Accueil et d’Orientation for asylum seekers (over 100,000 in the whole country in 2017, a true record). The report issued last October by Refugee Rights Europe on the area around Calais mentions about 700 people, mostly coming from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan. It also includes the first field enquiry – dating back to last October – about the reasons why many people live in these makeshift shelters and hope not to settle in France, but to cross the Channel, and why they prefer the United Kingdom to any other country. Less than 3 per cent of the interviewees said they would rather stay in France, while 92 per cent believe the UK is the best place to go.

Grande-Synthe is a minor junction along migration routes. According to the NGOs operating in this area, the Espace Jeunes du Moulin currently hosts 217 people. This number varies, of course, every time someone leaves without notice; the estimate counts 10 to 20 women, 100, sometimes 200 men, 10 to 25 children with their parents, and about 40-60 unaccompanied minors.

There is no official count, for this is only emergency accommodation against the biting cold. After the complaints of humanitarian organisations before Christmas, in Calais the French government only provided ten containers for women and children and a shed for men. The decision to open the doors of the Espace Jeunes du Moulin in December was taken and completely financed by the municipality, not the government.

Nevertheless, many migrants did not find any shelter and keep sleeping out in the open. As many as 150 people – including two families with young children – are living in Puythouck Park in Grande-Synthe. This encampment is already referred to as a “jungle” and is bound to get more and more crowded.

What will happen in April

“According to the prefecture’s decision, the municipality will only accept a part of the new applications to live inside the gym, and all accommodation centres will close on March 31 at the latest. They’re very strict on this point because they think that the presence of shelters is a pull factor,” Frances explains. “But migrants keep coming here and camping in Puythouck. The drinking fountain of the park was closed to deprive them of water, volunteers were asked to distribute food and medicines only inside the gym, the police keep confiscating tents and sleeping bags at dawn, even the branches of the trees were cut to prevent people from hiding there.”

As Frances admits: “We don’t know what will happen in April,” when the gym closes. As of yet, the prefecture of the Nord department and the subprefecture of Dunkirk have not answered any of our questions.

Macron and his new policy

The main goal of the French government is to eliminate the so-called pull factors, if not to force migrants to leave the country as soon as possible. After less than a year as president, Emmanuel Macron is openly willing to impose his viewpoint on this matter, and in such a firm way that – as the New York Times pointed out – his migration policy has been criticised by the French left wing more than by Marine Le Pen’s National Front.

At the end of September 2017, the Agence France-Presse obtained a copy of the new government bill on migration, which extends the detention period for foreigners awaiting deportation from the current 45 to 90 days. The judges of France’s national Court for Asylum went on strike against these measures during the second week of February. In the meantime, Macron passed from words to deeds and approved the government bill on February 21. The maximum period of detention has doubled; furthermore, the available time span to apply for asylum since arrival in France has been cut to 90 days, and up to one year of detention has been established for those who cross the Alps illegally. This law also gives more power to the police, allowing them to keep in custody migrants without papers for up to 24 hours, instead of the previous sixteen.

French Interior Minister Gérard Collomb had already voiced his will to oppose uncontrolled immigration in November. During the National Assembly for 2018 budget he declared: “We estimate that there are about 300,000 illegal migrants (…) we want to implement policies that compel all those who are denied asylum to leave the country.”

In an attempt to distance himself from those who accused him of inhumanity, including Human Rights Watch, Macron visited Calais on January 16 and spoke to a silent crowd of police officers: “You need to be exemplary, and you need to respect the dignity of each individual (…) If there are failings, they will be sanctioned, proportional to the confidence we have in you.” The audience did not applaud. At the same time, Macron chastised volunteers for helping the migrants and, in his opinion, encouraging “these men and women to settle in an illegal manner,” to which he added: “Under no circumstances will we allow the Jungle to come back.”

The agreements with the United Kingdom

Two days later, during the bilateral summit in London, Macron convinced British Prime Minister Theresa May to make a greater contribution to the prevention of illegal crossings and to speed up legal procedures for asylum in the UK.

His intention was to completely rewrite the agreement reached by Nicolas Sarkozy and David Blunkett in 2003, which moved the English border to France and allowed the British police to carry out controls and block any migrants without papers on the continental side of the Channel. That agreement still stands.

Macron would also like to persuade the English government to join their armed forces with those of France in order to create a new European defence force. But May’s spokesman stated that the Treaty of Touquet “has always worked for both parties” and did not comment on any potential review.

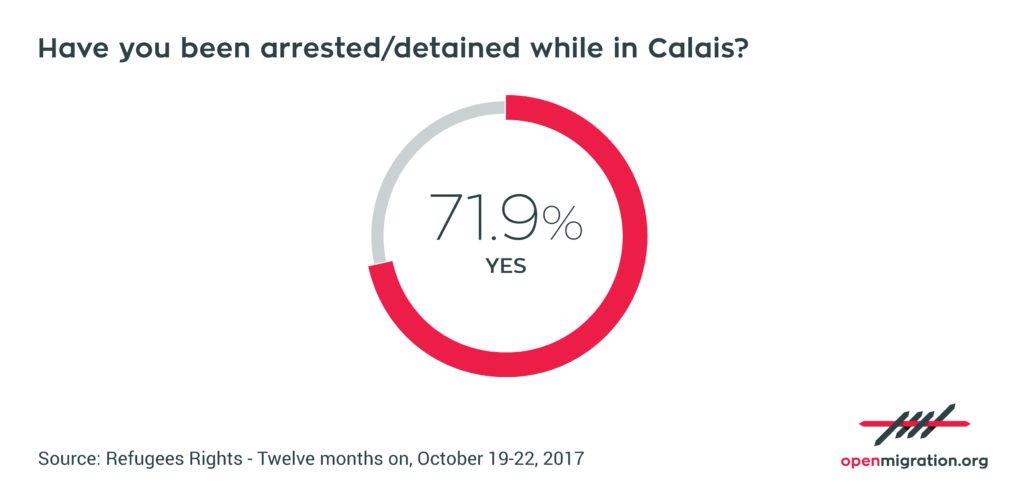

People hiding in “jungles” do so at their own risk, precisely so as to be able to leave the country at any moment. The report by Refugee Rights Europe reveals that a remarkable percentage of the people who were in Calais last October – about 72 per cent, including minors – had been taken into custody for some hours or up to 45 days, which was the maximum detention time until a few weeks ago.

“We are perfectly aware that, while we are working to help these people, the police could come in at any moment and take everything away,” Frances Timberlake says. “I believe that the main problem is the lack of logical procedures and safety. People need a place to stay and legal information as to whether they should remain in France or move to the UK. They often have no idea how to ask for assistance here or how to leave in a legal way.”

“We are perfectly aware that, while we are working to help these people, the police could come in at any moment and take everything away,” Frances Timberlake says. “I believe that the main problem is the lack of logical procedures and safety. People need a place to stay and legal information as to whether they should remain in France or move to the UK. They often have no idea how to ask for assistance here or how to leave in a legal way.”

Dying while dreaming the UK

Abdullah Dilsouz, a fifteen-year-old Afghan boy, was run over by a refrigerator truck on December 22. He was trying to reach his brother in London where he would have had the right to family reunification. Many accidents took place along the border in January, and the new agreement between France and the UK to speed up asylum procedures caused a 25 per cent increase in arrivals at the port of Calais, which exacerbated national tension.

On February 9 the dead body of a migrant was found on the A16 motorway between Calais and Dunkirk, near Marck. Another migrant was hit by a train in Rue Armand-Carrel on the night of January 14, and his legs were seriously injured. A truck with two Kurdish Iraqis on board hurt a policeman who wanted to inspect the vehicle in Grande-Synthe on January 17. The French Companies for Republican Security clashed with some migrants in Calais on January 25 while they were trying to dismantle an encampment close to the food distribution point in Rue des Verrotières. A sixteen-year-old migrant lost an eye. On February 1, at least five migrants were hit from close range while they were queuing for lunch, and a fight between Afghans and Eritreans spread across the entire city. Four Eritreans, aged between sixteen and eighteen, are still in hospital in critical condition.

Météo France and the Met Office register freezing temperatures. Those who choose to hide and not to move put their own physical and mental health at risk. In this context, the mayor of Grande-Synthe, Damien Carême, announced that the city will host the national convention on reception and migration on March 1 and 2: “Two days of debates, reflection, and roundtables to deconstruct the repressive approach of migration policies.”

Meanwhile, people keep trying to get organized and find a lift on some truck in order to go away. One of the families that left Grande-Synthe managed to cross the border and reach Dover on the last Sunday of January.

Naza and Birwa did not make it, and they are still living in the Espace Jeunes du Moulin, where volunteers from Gynsf provide regular health care to Birwa and the baby that will be born two months after the evacuation of the gym.

Cover photo: Grande Synthe – Naza putting toys into her backpack when she hears that she may finally be able to go to England (photo by Emanuela Barbiroglio).

Translation by Lucrezia De Carolis. Proofreading by Alex Booth.