From the late afternoon on, the pavements around Catania’s railway station start filling with young girls waiting for their customers. Lucia Genovese, who works for the street unit of the Penelope association, has been meeting them for years to offer her help and support. “Together with my fellow workers, we move around the main roads or the city centre, depending on where they station themselves. Each place has its own peculiarities, but Nigerian girls are everywhere,” she says. Their presence seems to have strongly increased in the last months: “Previously we managed to cover the entire city with one street unit [one of the ways to approach trafficking victims], but now it’s impossible. We were forced to split it up into areas.”

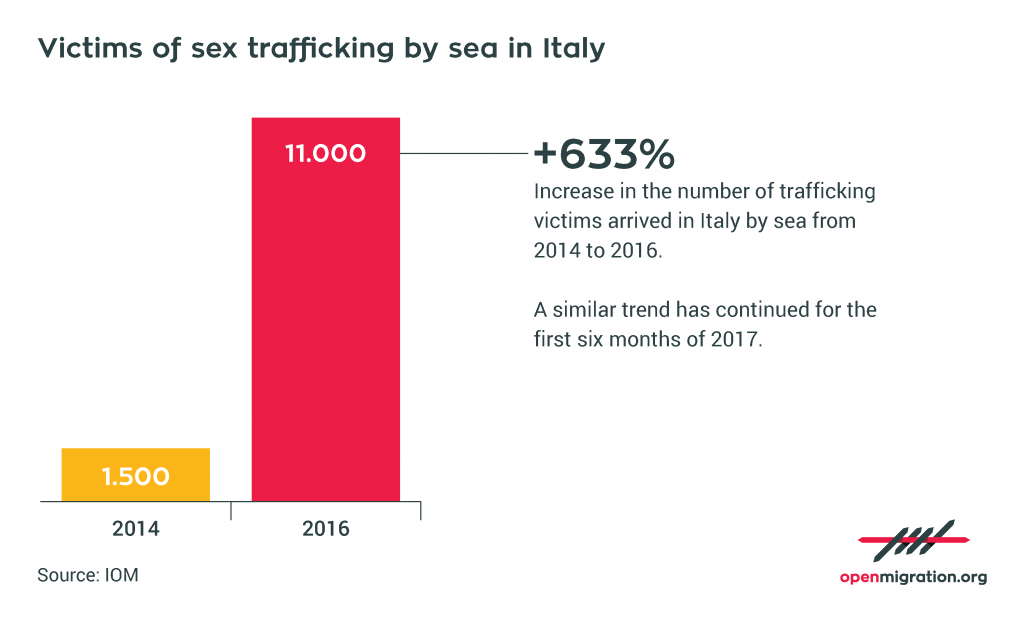

In fact, the “sex trafficking” phenomenon is experiencing exponential growth. According to the latest report of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the number of potential human trafficking victims arriving in Italy by sea has increased by more than 600 per cent over the last three years, soaring from 1,500 in 2014 to more than 11,000 in 2016. In Italy, almost all of them are Nigerian women. This growing trend has continued for the first six months of 2017 too.

The victims are very young girls, mostly under-age, coming from different regions of Nigeria: Edo, Delta, Lagos, Ogun, Anambra, Imo. In 2016, the country ranked first in terms of number of arrivals on the Italian coasts, with a particular increase in women and unaccompanied minors. IOM maintains that about 80 per cent of those Nigerian female migrants who arrived by sea in 2016 ended up being exploited as sexual slaves.

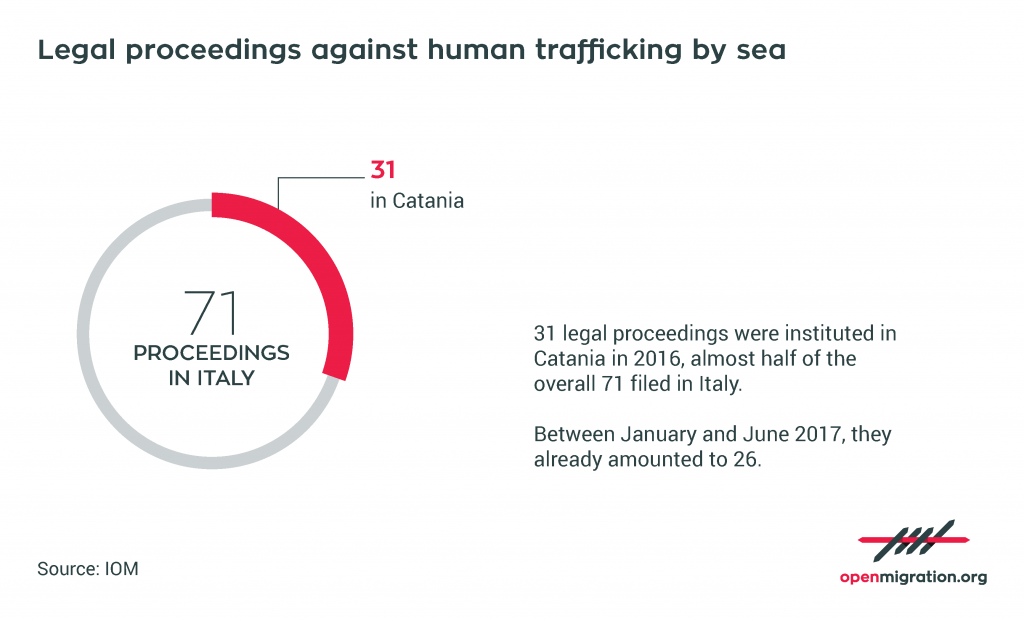

“Sex trafficking is an extremely complex phenomenon that proves very difficult to fight. In Italy we are only able to see a part of it, from the arrival on our coasts onwards,” explains Lina Trovato, the public prosecutor trying to counter trafficking from one of the most active prosecutor’s offices in all of Italy: Catania. As many as 31 legal proceedings were instituted here in 2016 – almost half of the overall 71 that were filed in Italy. Between January and June 2017, there were already 26 legal actions, and they seem bound to exceed last year’s figure.

Nigeria, where trafficking begins

The first stage of the process is “recruiting”: the girl is approached by a friend, relative, or someone she trusts who offers to help her reach Europe and put her in touch with other people. “This proposal aims to lure girls in extremely poor living conditions. Sometimes they are perfectly aware of what awaits them, but they consider it a better perspective,” Trovato says. In larger families, it is often the elder daughters who undertake this journey to help their relatives. Unfortunately, most of the time, the victim has no idea of what will happen: somebody tricks her by talking about a friend who is looking for a shop assistant, hair-plaiter, or babysitter in Italy.

According to IOM’s report, “the ever earlier age of Nigerian girls arriving by sea is inversely proportional to their awareness of sex trafficking and of the violence and abuse” they will face. Several teenagers confided to the operators that “they have never had sexual intercourse and are completely unaware of contraceptive methods or the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases,” and that they seem to have no idea of “what prostitution means.”

The second step is the voodoo ritual where a Juju spell is cast: the girls must agree to pay back those who bring them to Italy (usually between 25 and 30,000 euros) without escaping, calling the police, or naming their traffickers. The main threat in case of disobedience is death, either for them or for their relatives.

This spell is one of the elements that ties thousands of women to sexual slavery. According to IOM, voodoo is a widespread “psychological control method” in Nigeria, where it represents a “warranty of loyalty and, above all, silence, even when the migrant discovers what her real condition is going to be.” In a reportage published by Thomson Reuters Foundation a shaman in the village of Amedokhian, in southern Nigeria, explains how he scares the girls after making them drink “concoctions brewed with pieces of their own fingernails, pubic hair, underwear, or drops of blood”: “I can make sure she [the girl] never sleeps well or has peace of mind until she pays what she owes […] Something in her head will keep telling her: ‘Go and pay!’”

From Nigeria to Italy through Libya

Once the voodoo spell has been cast, their commitment is solemn and the debt to the madam – a sort of brothel keeper – becomes a contract. The first part of the journey, from Nigeria to Libya, begins across Niger.

The request for this journey comes from Italy or from groups operating between Nigeria and Italy. The roles of the chain are very specific: an on-site recruiter, a person in charge of the voodoo ritual, the madams, and those who take care of the girls in Italy, plus some intermediaries along the way. If the person escorting the girls is “almost at the same level as the one organising the journey (the so-called connection man), he is called a boga,” Trovato explains. If he is just appointed by the recruiter, he’s a trolley-man. Then, once in Italy, there is a ticket-man who, according to the madam’s instructions, picks up the girl from the centre she finds herself in, pays for her ticket, and puts her on a bus bound for her final destination, usually in the north.

The report entitled “Young Invisible Enslaved” by Save the Children reveals that over the 715 kilometres from Kano (Nigeria) to Agadez (Niger), young victims “suffer violence and forms of coercion at the hands of the smugglers or the many other people who are in some way involved in organising irregular migration (for example, corrupt border police or criminal gangs).” Then they leave Agadez for the border, crossing 3,500 kilometres of desert “in pickup trucks overloaded with people.”

After Niger, the girls arrive in Libya, where violence and physical abuse seem to be the rule. “They are lodged in a ghetto, safe house, or connection house. Their fate depends to a large extent on the wealth of those who asked for them: if they are rich, the girls will receive food without being forced to prostitute themselves,” Trovato says. But most of the time economic conditions are not so good and, generally speaking, migrants tend to stay in Libya for a longer time with a consequent increase in costs. Sometimes the madams run out of money and the connection men decide to sell the girls to other smugglers.

Furthermore, according to IOM the cases of sexual assault involving people not directly connected to the trafficking network have increased over the last year because of ever-growing instability; as a consequence, more and more women are already pregnant when they arrive in Italy. Sometimes, when a madam discovers that the girl is with child, she decides to ‘abandon’ her in Libya in the hands of local pimps who will force her to have an abortion and work in their brothels.

The arrival in Italy

Irene Paola Martino, a midwife working on one of MSF’s ships in the Strait of Sicily, reports that “in every boat that reaches our ports there is always a large group of Nigerian girls, many of whom are under age […] When you separate them from the other migrants, little by little they open up and disclose their unbelievably violent stories.” But “as soon as they disembark, most of them change their attitude instantaneously: they keep their eyes lowered and stop answering questions.”

These girls usually arrive in Italy with telephone numbers written on slips of paper, which they carefully wrap in plastic to protect them from sea-water and then hide. They always try to follow the directions they were given by the people who escorted them in their journey.

According to Trovato, “smugglers know the Italian system perfectly. For this reason, they instruct the girls to pretend they are of age — because that way they’ll be more free — and to tell a certain story. Apparently, Libya is full of ‘benefactors’ who help young girls leave.”

Most of the time victims pretend that the smugglers are their uncles, husbands, or brothers so as not to be separated from them. But, as IOM clarifies, they are actually the bogas, “who will hand them over to the smuggler waiting for them in Europe. In criminal networks, they are nothing but carriers who deliver ‘goods’.”

This is why effective identification upon arrival is fundamental. In its latest report, the GRETA (European Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings) highlighted that Italian authorities carry out this procedure too hurriedly to notice any trafficking victims.

A difficult investigation

When Trovato began to deal with trafficking she was struck by the huge difference in numbers between IOM’s reported cases and legal proceedings in the prosecutor’s office of Catania: “I wondered how it was possible that the Organisation for Migration reported so many trafficking victims while we only had two or three dossiers,” she recalls. Then she started tracing the girls’ stories backwards, sifting through the lists of disembarked boats and vulnerable cases signalled to the juvenile court.

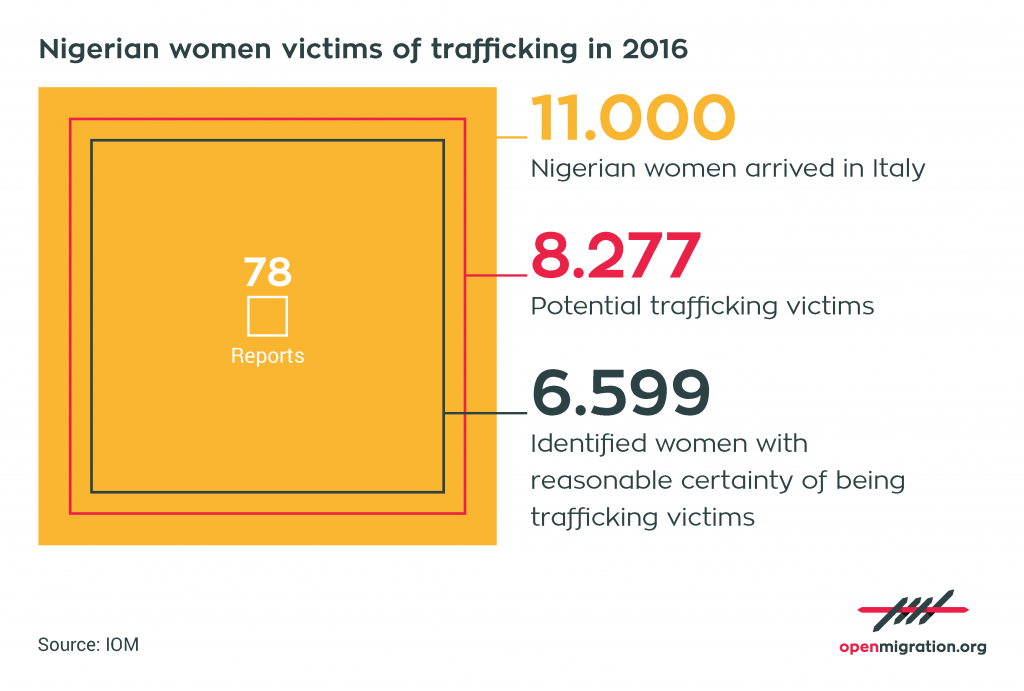

Only a handful of them had been reported to the police. Approximately 11,000 girls from Nigeria arrived in Sicily, Apulia, and Calabria in 2016: according to IOM’s indicators, 8,277 were potential trafficking victims, 6,599 of whom were identified as such with some reasonable certainty. Despite these numbers – already lower than reality – only 78 cases were denounced.

In the opinion of Oriana Cannavò, head of Catania’s section of the Penelope association, “fear often prevails. The choice is far from simple; it is about giving up a certain kind of life the girls were expecting, a migration project that turned out to be a fraud.”

Another important aspect concerns the spell and the threats to the girls’ relatives in Nigeria: when the girls refuse to reach the madams as soon as they can, local criminals scare their parents who in turn immediately go after their daughters. Many of them yield to the pressure and, though they had started to cooperate with the police, go back to their exploiters.

Since it is impossible to rely on victims’ testimonies, investigations usually begin when the juvenile court or prosecutor, a guardian, or a reception centre operator reports a particular case. “For example, twice we started from a centre where a suitcase with a mobile phone and a pair of stilettos was found,” Trovato says.

Since it is impossible to rely on victims’ testimonies, investigations usually begin when the juvenile court or prosecutor, a guardian, or a reception centre operator reports a particular case. “For example, twice we started from a centre where a suitcase with a mobile phone and a pair of stilettos was found,” Trovato says.

In many cases even the victims’ statements are unreliable. “Girls do hate their madams, but they are also grateful to them for helping them reach Italy. It is very difficult to obtain their names,” the prosecutor explains. Some girls even say their madams found them crying on the street and took them in. In these cases, they can be charged with giving false testimony. This is the reason why “we need lawyers who are trafficking experts, so that during their depositions the girls can admit they have lied out of fear.”

Investigations also reveal that these kinds of criminals are primarily Nigerian. Furthermore, 80 per cent of those arrested are women. The ugly truth behind this figure is that almost all of them are former victims. “Trafficking is a vicious circle: many girls not only hope to free themselves and pay off their debt, they also want to become madams themselves after a few years so they can find another woman to replace them on the street,” Trovato reveals. Sometimes they are even encouraged by their parents. “During an investigation we listened to a phone call with a girl’s mother who was saying to her daughter: ‘Don’t give up! Today you are at her service, but in a year’s time, if you’re lucky, you’ll have someone at your service’.”

Escaping human traffickers

The street unit is one of the ways to approach trafficking victims. Operators mostly give healthcare support: blood tests, termination of pregnancy, medical examinations. As Lucia Genovese clarifies, “we don’t talk about protection programs because on the streets you might run into a madam.” Non-verbal communication is fundamental in these conversations: “If I ask a girl some questions and she keeps looking at the same person before answering, I try to make up an excuse to have her come to my office. Some of them actually end up opening their hearts.” But not everyone decides to talk to the police. “Some want to continue paying because they are too afraid for their family,” the operator explains. Others, despite having paid off their debts, keep prostituting themselves or become madams.

As provided for by Article 18 of the Consolidated Law on Immigration, those who start a protection program are granted a special residence permit. They are accommodated to specific facilities, some of which have secret addresses, and supported by the association in every aspect concerning contact with police headquarters, deposition (which is always a traumatic moment), school enrolment, and apprenticeship activation. The goal is to make them independent, in spite of the difficulties.

In February 2016, the Italian Council of Ministers adopted the National Plan against Human Trafficking to systematise some courses of action. One of the objections raised by the associations working in this sector is that the funds to counter sex trafficking continue to be connected to single projects without being used at a structural level. As Cannavò highlights, “I would like to see Penelope’s activity become systemic and the fight against human trafficking become a constant priority for institutions. This plan was expected, and it certainly represents a turning point. But it’s only a drop in the ocean.”

Translation by Lucrezia De Carolis. Proof-reading by Alex Booth.

Cover photo: Shortly after dawn two young victims of sex trafficking emotionally observe the entrance of the Aquarius ship into the port of Augusta (photo: Federica Mameli)