For several months now, asylum-seekers, including unaccompanied minors and families, have been subject to Belgium’s buckling, inadequate asylum reception system.

Tensions are high. Hundreds of asylum-seekers are sleeping on the streets, illness and scabies have been spreading, and many are enduring hunger. This set of circumstances is partially due to the government closing centres when the number of asylum applications dropped temporarily, only for this to cause a staggering shortage of places when applications sharply rose again, including after the return of Taliban rule in Afghanistan.

Within the reception system, Fedasil staff have gone on strike and the Belgian state is facing fines and a growing pile of interim orders ordered against it by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). More interim measures are likely to be added to that pile as Rule 39 applications continue to be received by the ECtHR and worst of all, as the weeks progress without the reception crisis finding resolution, the worst of winter is fast approaching. As human rights organisations continue to sound the alarm and apply, on behalf of hundreds of applicants, to the ECtHR for interim measures in an attempt to save asylum-seekers from irreparable harm, there seems to be no plan in place for Belgium to implement emergency measures with immediate effect. At this point, it seems the brunt of the winter cold will be borne by vulnerable asylum-seekers, and the consequences this will have for their lives and health is terrifyingly unclear.

The registration centre of the Federal Agency for the Reception of Asylum-Seekers (Fedasil) – the Belgian department responsible for the reception of asylum-seekers – is overwhelmed. Staff working in the Labour Court of Brussels, which is where domestic remedies for government failures are typically sought, have been buckling under the sheer weight of applications for rectification of Fedasil’s failure to provide shelter for asylum-seekers. Fedasil has been condemned by the Labour Court a stunning 6,000 times in a single year just with regard to accommodation for asylum-seekers. Earlier on in 2022, Brussels’ Court of First Instance condemned the Belgian state for its failure to provide shelter to asylum-seekers.

The State has so far been ignoring the convictions issued against Fedasil, failing to intervene to ensure that this agency has more capacity and that new shelters are constructed. Fedasil may indeed perceive that there is little risk in its failure to comply as, being an agency of the Belgian State, rather than the State itself, when they do not comply with order to provide shelter interested persons who activate execution proceedings against Fedasil likely will not be able to recover anything via that route as Fedasil itself does not have property that can be seized via execution orders.

Regardless of the reason for lack of compliance with court orders, this lack of action by the Belgian State/Fedasil is prompting those affected to approach the ECtHR for interim measures, as this is a way to obtain a judgement ascertaining responsibility of the Belgian State as an entity, and not only Fedasil.

Some asylum-seekers have been waiting several months for accommodation. For example, in one case, concerning Guinean Asylum-seeker Abdoulaye Camara who was denied accommodation in a reception facility in July this year, the intervention of the Brussels Labour Court in July, which ruled against Fedasil and asked that he be given shelter, was of no assistance. Interim measures from the ECtHR in the case of Camara v. Belgium followed in early November – compelling Belgium to comply with the order made by the Brussels Court and provide Camara with accommodation and material assistance to meet his basic needs.By this stage, Camara had been sleeping rough for months, suffering from hunger and health problems (including scabies, which has been rampant amongst groups of homeless asylum-seekers, made worse by poor sanitation conditions).

Alike Camara, hundreds of asylum seekers have been forced to live on the streets, fearing the temperatures dropping and the winter approaching.

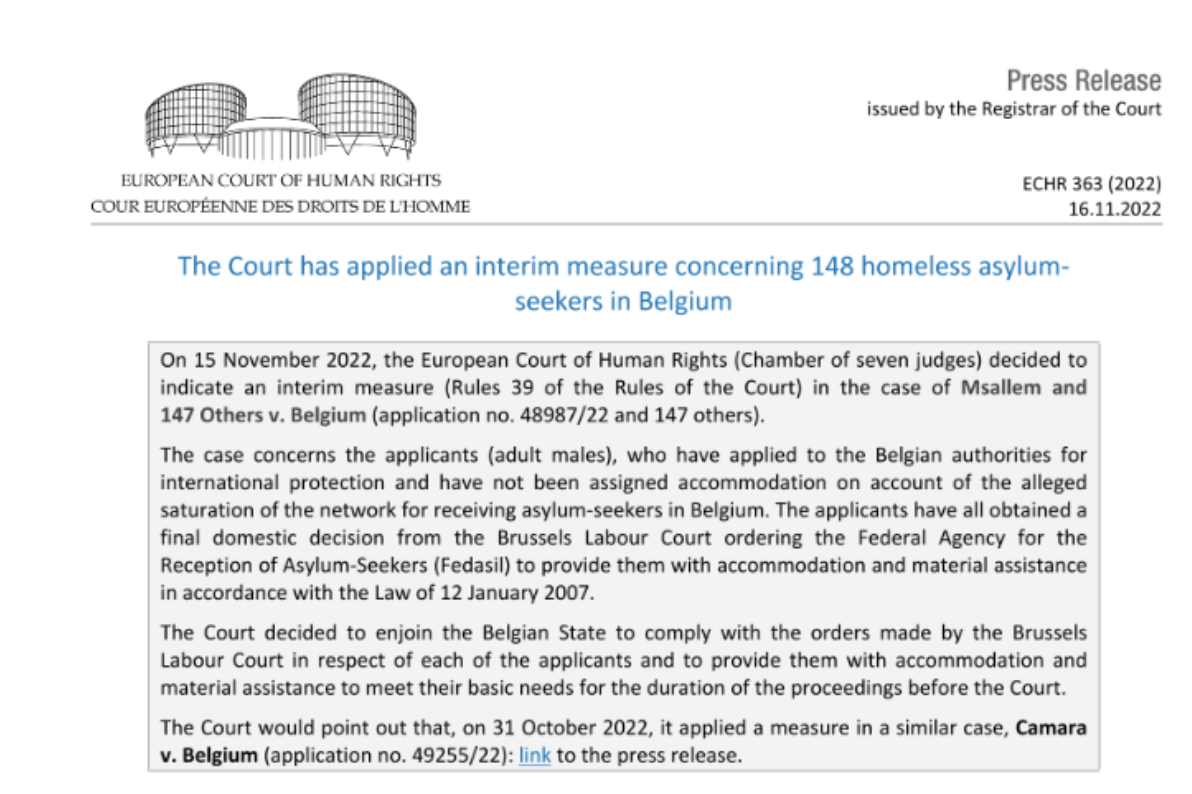

The remarkable mobilisation of civil society, and cooperation between NGOs and pro bono Initiative such as the First line Legal Helpdesk for Asylum Seekers in Belgium (“Legal Helpdesk”), run by the Brussels Bar Association and Vluchtelingenwerk Vlaanderen and CILD’s Rule 39 Initiative, have ensured the increased involvement of the ECtHR in this issue in the past few months. Just under 3 weeks ago, following the Camara judgment, the ECtHR spectacularly ordered interim measures for the simultaneous benefit of an enormous 148 Rule 39 applications submitted on behalf of 148 asylum-seekers of various nationalities, living in Belgium without accommodation. This is particularly significant as the ECtHR only grants such measures “in exceptional cases, only when the applicant otherwise faces a real risk of irreversible harm.”

In all 148 cases, the Court ordered the Belgian State to comply with the decisions issued by the Brussels Labour Court in respect of each applicant and to provide them with accommodation and material assistance to meet their basic needs. This result was addressed in a press release by the Court, in the case of Msallem and 147 Others v. Belgium (application no. 48987/22 and 147 others).

Unfortunately, the numbers of asylum seekers still living on the streets remain very high. Fearing winter, many have taken refuge in a former federal government building managed by the Region of Brussels and located in Schaerbeek, notably in Rue de Palais. On 24 October 2022, when the first group of asylum-seekers entered the building, it was still undergoing important renovation work, meant to render it suitable for accommodation of Ukrainian refugees (ironically, noting that such renovation work was not commenced for the Afghan refugees which had been incoming before Ukrainian refugees). The number of occupants in the building has since grown considerably, reaching over 800 people as at the end of November.

Of the over 800 people currently living in the building on Rue des Palais, the majority are asylum seekers, including women, children and unaccompanied foreign minors. An action to evict the occupants of the building was started on 8 November 2022 by the current owner and a judgment was handed down on 17 November 2022 by the Justice de paix du premier canton de Schaerbeek, stating that the occupants had 3 weeks to vacate the premises.

The conditions in the Rue des Palais building are a risk to occupants both in terms of security and sanitation, with electrical boxes easily accessible, a defective sewage system, unstable walls, open elevator shafts, and undrinkable water, aside from many other significant health and sanitation defects. Local authorities fear cases of diphtheria, scabies and possibly tuberculosis amongst the occupants, and some occupants are gravely ill with no access to medical care.

Many of these occupants make up a new group of potentially up to 700 applicants, who either have applied, or will shortly apply, to the ECtHR for Rule 39 interim measures. They are assisted by an informal committee of support composed of NGO representatives and private individuals (including lawyers who volunteer their time for actions before domestic tribunals) and by CILD’s Rule 39 Initiative, both of which have been working tirelessly to give affected asylum-seekers access to justice, including in the form of submitting Rule 39 applications on the matter to the ECtHR.

Applications on behalf of 58 applicants were lodged on Monday, having been drafted by volunteer lawyers hailing from 8 international law firms within the Rule 39 Initiative, led by Dr Daria Sartori.Applications on behalf of another 30 are set to be lodged on Friday, again drafted by those within CILD’s Rule 39 Initiative.

If the Belgian State is of the opinion that ignoring judgments will make the attention to this problem start to wane, they are very likely mistaken, as applications to the ECtHR in December will outnumber those in November by at least 400%.

It is also possible that those affected may also seek compensation via individual applications in the ECtHR eventually. Without urgent additional attention, the situation in Belgium is likely to continue to compound and snowball rapidly, in terms of both consequences for the State but also, terrifyingly, irreparable consequences for asylum-seekers as local temperatures plummet and illness spreads.

Still, the Belgian government is opposed to moving forward with a more formalised “disaster plan”. While it has announced a package of measures to tackle the asylum-seeker reception crisis, including more reception centres, and reportedly plans to refuse approximately 5000 Afghan asylum applications in an attempt to free up additional places in reception facilities, the Government have so far refused suggestions for more immediate measures, including suggestions from civil society to make emergency accommodations in hotels available.

Indeed, instead of focusing all efforts in response to the issue on improving their adherence to international law and rule of law, Belgian State Secretary for Asylum and Migration Nicole de Moor said in an interview that part of their focus is on “prevention” including via increasing forced return.

Noting these positions held by the Belgian government at present, it seems inevitable that, unless more immediate solutions (including those rejected thus far) are implemented, and rapidly, Belgium will continue to violate rule of law by denying asylum seekers the right to reception and continue to violate both national and international legal frameworks. A reality which is disappointing, noting that the EU’s response to Ukrainian refugees evidenced clearly that in the case of a sudden influx of refugees, that where there is a will, there is a way.

Cover photo by Todd Mecklem/Flickr