Mohammed never smiles. Since his father and sisters went back to Raqqa, Syria, his life has become even more complicated and frustrating. Mohammed is 25, but he speaks like a 40-year-old man; since 2013, he has been living on a strip of land covered with tents and rubble that make up the Sarada refugee camp in southern Lebanon.

“My father is not very happy that he went back to Syria. Jobs don’t last long, you only earn a few dollars a day,” he tells us. Some months ago his relatives reopened the family home in Raqqa, which was destroyed by the bombs they had fled. “My sisters are optimistic about it. One has even found a job at an international organisation, while the other has gone back to university. She had almost finished but her exam transcripts got lost, so she had to enrol in third year.”

Mohammed’s father and sisters are among the 8,000 or so Syrian refugees who have decided to go back to their home since the beginning of 2018, as the conflict is subsiding. A few months ago, an agreement between the Syrian regime (which has regained control of most territories) and the Lebanese government produced a voluntary repatriation programme. Returning Syrians to their home country 7 years after the eruption of the civil war is becoming an increasingly pressing political issue in Beirut’s places of power. There are 1 million Syrian refugees here, 1.5 million according to the Lebanese government, a staggering number for such a small country, at just over 10,000 square kilometres, with only 4.5 million inhabitants, and professing a variety of religions. In 2015 the Lebanese government introduced more restrictions for the renewal of residency permits (Lebanon has not signed the Geneva Convention and does not recognise the status of refugee), and called on the UNHCR to temporarily suspend the registration of Syrian refugees.

The small cedar state fears a demographic upheaval like the one that followed wave upon wave of Palestinian refugees with the proclamation of the State of Israel 1948. The UN, however, claims that the situation is not conducive to the return of refugees to Syria.

“UNHCR conducted return intentions surveys among Syrian refugees in Lebanon in 2018, and 88% stated that they wish to return to Syria,” Lisa Abou Khaled, a spokeswoman for UNHCR Lebanon, explains. “There are two types of return movements, those who return on their own (spontaneous returns) to Syria and those facilitated by the General Security. In 2017, UNHCR recorded around 11,000 spontaneous return movements that we have been able to de-register and so far this year in 2018 we are aware of around 4,423 individual returns. There are indeed more spontaneous returns that we are not capturing but we do not have this number. As for the General Security-facilitated movements, UNHCR receives the numbers from the General Security. So far this year, we have been present at over 30 such group returns, whereby around 7,698 individuals returned to Syria. While UNHCR is not organizing returns of refugees to Syria at this moment, UNHCR is continuously and relentlessly working to help identify and remove the various obstacles that refugees see to their return to Syria, so that a larger number of refugees are able to return in safety and dignity.”

The refugees’ desire to return is at odds with the reality of an unstable country, still ruled by dictator Bashar al-Assad, who brutally repressed the uprising of 2011 and plunged Syria into a bloody, seven-year civil war.

Mohammed himself does not want to go back, because like other men of his age, he is a deserter: he did not serve in the military and fears retaliation at the hands of the regime. “I don’t want to be in Lebanon, or in Syria. They are both places where it’s hard to think about tomorrow,” he continues. “Now I’m living in a tent, I’m in limbo. If I had one wish, I would like to go to Europe because I don’t want my children to blame me one day for bringing them into the world and then having them live like this.”

The harsh living conditions in Lebanon are why some Syrian refugees have begun to go back. In April, research from Beirut’s Carnegie Institute showed daily instances of racism against refugees, with low-income residents, such as those housed in informal settlements, forced to eke out a living in the fields or on construction sites.

“Here we work odd jobs for a few dollars. We pay 20 dollars a month in rent to keep our tent; my children have wasted their best years here. But we don’t want to return just yet,” 32-year-old Ahmed explains. He lives with his wife and their 4 children in Marj El-Khokh, another informal settlement housing a thousand souls. Most of them came from Idlib, an area with 3 million inhabitants, which has become the last stronghold of the Syrian rebels. A fragile truce has so far averted a fresh humanitarian catastrophe; that is, until Assad unleashes his final attack, as he has announced multiple times.

“We fled 5 years ago, our children have grown up here in this tent, and they haven’t had many opportunities. They don’t get to attend school very often, it’s not enough. I can say that my wife and I, and our kids especially, have been denied a future.”

The return of refugees is a powerful political weapon for president Bashar al-Assad in his quest for international credibility as a stable leader. It is instrumental to the reconstruction of the country, an ambitious plan being thwarted by a dwindling workforce. Most young people have fled, while those who have remained have been sent to fight in the army. “Some of the obstacles cited by refugees include the risk of having to join the military and fight, or not being able to recover their land or property in Syria, or access to basic services. This is why UNHCR is continuously and relentlessly working to have these obstacles removed, including through raising these obstacles with the concerned authorities inside Syria and discussing ways in which they can be removed.” Abou Khaled continues.

On October 9th, President Assad announced a general amnesty for army deserters. As the Syrian press agency Sana pointed out, however, the offer does not cover “criminals”. This term broadly describes all those on the run from the law, as well as all political opponents to the regime, who must first turn themselves in to the authorities if they want to benefit. But Syrian jails, as numerous reports from human rights groups have warned, are a black hole. An institutional hell where inmates can be arbitrarily tortured and killed.

Politics aside, the grand reconstruction scheme advertised by Assad, who has remained firmly in power also thanks to the inertia of Western countries, hinges on a number of very specific goals.

Earlier this year, Syria passed Law Number 10, which empowers the government in Damascus to create redevelopment zones in low-income neighbourhoods, often the very ones that the refugees in Lebanon come from. Those who return could find their homes already demolished under the new redevelopment scheme. They might have to settle for a refund, but only if they are can provide proof of ownership, or relocation at the regime’s discretion.

Milad knows this well. From his tent in Marj el-Khokh, where he lives with nearly a dozen relatives including his mother, wife, children and nephews, he follows the news from Idlib province almost obsessively.

“I am not willing to go anywhere that is not my home, I’d rather live in a tent next to the rubble until I have the means to rebuild my home,” he explains.

A small veranda outside Milad’s tent signals the presence of many women. A concrete platform covered by tarp, with a window opening onto it. One can sit on the floor, sip some tea and look at the Mediterranean brush stretching all the way to the Israeli border.

“Life here is tough, we work for a few dollars but the political situation in Syria is unstable, we cannot trust it to be safe.”

The refugees’ fears are rooted in the traumas of war. The stories of the people one meets among the refugees in Lebanon are all very similar. One common thread is the memory of the bombings, which are marked indelibly into their psyche. This is especially true of children.

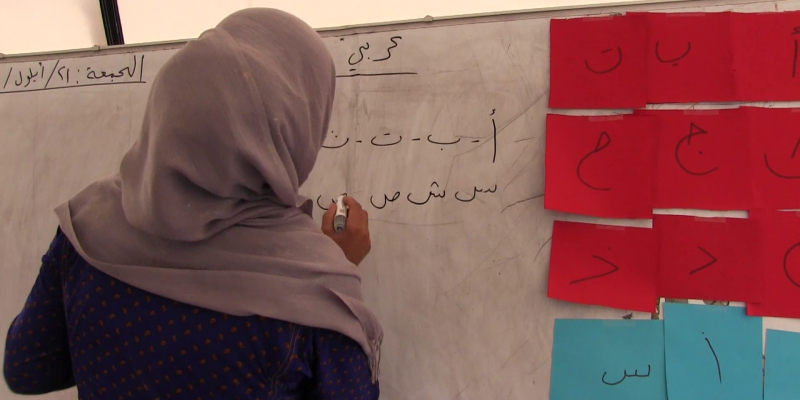

“If I were to return right now I would only be very afraid. My children have been traumatised by the bombings. Whenever they hear the sound of a plane, they are terrified, even though it’s been 5 years. They run for cover every time, thinking the bombs are about to drop again,” Aida tells us. She has a sweet, round face, framed by a blue hijab. She looks like an actress out of a musalsal, the TV shows that are broadcast by pan-Arabian networks during Ramadan, the Muslim holy month. She also fled Raqqa province in 2013, walking amid the bombs. Even then she had four children, and is now expecting her fifth. She cannot read or write. She is currently learning in the Sarada camp, thanks to an initiative by AVSI, an Italian NGO. “Of course I would like to go back to Syria, but this is not the right time. Part of my family has stayed in Raqqa. I haven’t seen them in five years and I don’t get to hear from them very often. All I know is that my home was completely destroyed; we have lost everything.”

Fear of new conflicts, as well as the lack of employment and of social justice are the reasons why mass returns remain a utopia at present, as Assad has remained firmly in command since the war broke out following the riots of 2011. His aspirations of stability, however, are perceived by the most attentive observers as nothing more than a fragile and vague show.

Cover photo: Aida at Avsi literacy programme, Sarada camp (photo by Laura Cappon, like all pictures in this article)