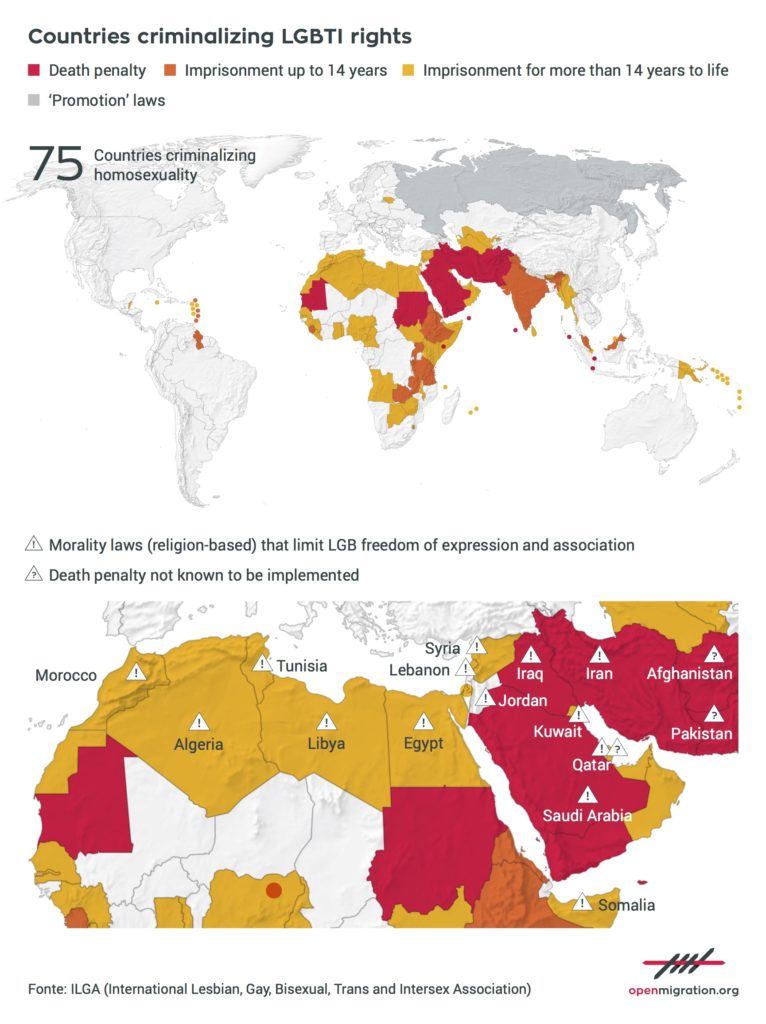

Among those asylum seekers who arrive in Europe every year, there are thousands who have left their countries after becoming the victims of violence and persecution, also on the basis of their sexual orientation. According to the annual report by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), 75 countries worldwide criminalise homosexuality. In 13 countries – including Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, homosexuality is punishable by death; in 14 countries, being gay can lead to a life sentence, and in other countries to imprisonment up to 15 years, as in Angola, Kenya, and Morocco. Finally, laws have been passed in 17 countries (such as Russia), that limit LGBTI freedom of expression.

The issue of the criminalisation of homosexuality and transsexuality has only recently begun to draw international attention. An NGO dedicated to LGBTI refugees, the Organization for Refuge, Asylum & Migration (ORAM), which is also an official partner of UNHCR, was founded only in 2008.

This belatedness explains the paucity of studies and statistical data, a fact that was also certified by the first report on homophobia in Member States by an EU agency for fundamental rights, which denounced a “significant lack of both academic research and unofficial NGO data regarding homophobia, transphobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in many Member States and at the EU level.”

Who LGBTI refugees are and where they come from

Obtaining reliable statistics on the numbers of LGBTI asylum seekers is very difficult. On the one hand, it is a very sensitive issue; on the other hand, the majority of EU Member States do not collect data on the phenomenon. In 2002, the number of applicants seeking asylum in Sweden on grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity was estimated to be approximately 300 per year. In the Netherlands, the applications of homosexual and transgender asylum seekers amount to approximately 200 per year. However, according to the research Fleeing Homophobia, co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, these estimates are most likely very conservative. The same research maintains that LGBTI applicants come from at least 104 countries throughout the world.

Official records are also scarce in Italy, and what little documentation we have exists thanks to the efforts of local associations, which is still too patchy to provide us with the bigger picture. Many claimants come from Gambia, where dictator Yahya Jammeh has gone on record saying he would eradicate all homosexuals; or from Senegal, a country with extremely severe punishments. Some are from Egypt where homosexuality is not, strictly speaking, a crime, but where other laws, such as the ones on public morality and religion, are used to target homosexuals with raids and mass arrests. Giorgio Dell’Amico, who is in charge of immigration for Arcigay, tells us as that those seeking the help of local groups operating in several Italian cities are from Middle Eastern, African, South American, and Asian countries, and that they are not necessarily Muslims. Furthermore, most cases involve gay men, which leaves us in the dark on the plight of lesbians, transsexual, and intersexed people.

Forced to flee to avoid a lifetime of imprisonment or secrecy (in the best case scenario), LGBTI refugees and asylum seekers often find themselves facing xenophobic or homo-transphobic discrimination in their host countries; looked upon with suspicion by both their communities of origin and their new neighbours, they live a kind of double stigma, which is compounded by an inadequate response on the part of local institutions.

The difficulties of seeking asylum

According to the UN Geneva Convention of 1951, anyone who is unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a “well-founded fear” of being persecuted for “reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion” can claim the status of refugee. A EU Qualification Directive later included sexual orientation in the definition of “social group”, which was subsequently upheld by national and European laws.

Photo: Nicky Rowbottom (CC BY 2.0).

Despite being potential beneficiaries of international protection under the law, things are not that simple for LGBTI asylum seekers. Trouble begins as early as they meet with the Territorial Commissions in charge of reviewing their applications, which are often not equipped to deal with so-called SOGI (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity) claims.

“The difficulty for the Commissions lies in determining whether the statements of those who claim to have been persecuted on grounds of sexual orientation are credible,” Livio Neri, an attorney with the ASGI (Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration) explained, adding that “the assessment is conducted in a somewhat crude fashion” even though the issue is a very sensitive one.

During the audition, for instance, asylum seekers may be asked about difficult or embarrassing details, or be posed questions that display a lack of knowledge of their cultures of origin. “The interviewers demand an awareness of sexual orientation that the applicant may or may not have, as is more often the case,” Neri explained. “If you ask any 21-year-old African man if he intends to marry and have children, he will reply that he does, because he takes that for granted and thinks that is what makes him a good person. He does not imagine that his answers could be construed as incompatible with his stated sexual orientation.”

Until a few years ago, as noted by the Fleeing Homophobia researchers, in various European countries medical examinations were used to determine the sexual orientation of asylum applicants that were below the standards required by international human rights law, such as phallometric testing or physical response to pornographic images. Examinations also relied on stereotypes: non-effeminate gay men were excluded, as well as applicants who had been married to someone of the opposite sex.

These practices have never been used in Italy, but there is still a long way to go. “Often, in a meeting with the Commission or in court, applicants are asked to give proof of a homosexual relationship or affiliation with an LGBTI group. However, for many of these people, coming out as gay is a taboo even to themselves,” Neri explains, adding that one of the most frequent mistakes that the Commissions make is to ask the applicant point-blank whether he or she is homosexual or not. “Just think,” he continues, “of someone coming from a country like Gambia where they faced a death sentence. They land in Lampedusa and are asked if they’re gay: how are they going to reply? It’s one thing to bring oneself to recount one’s experience in a gay relationship, it’s another to identify as gay.”

The criteria for verification of an applicant’s sexual orientation were also the subject of a series of decisions made by the Court of Justice of the European Union, which recommended particular caution and called for a ban of invasive techniques. The UNHCR had already intervened in 2012 when it published its Guidelines on International protection No. 9 dedicated to SOGI claims, which also banned excessively detailed personal questioning or practices that violated the applicants’ human dignity.

All of these difficulties demonstrate that the case of applicants pretending to be homosexual in order to expedite their asylum process – reported by certain Italian newspapers – is extremely rare. “There is an element of that, I won’t deny it, but it’s not at all common. They are actually a minority, because there is such a stigma attached to identifying as gay,” Dell’Amico explains.

The double stigma of LGBTI refugees

LGBTI asylum seekers are doubly discriminated against: once as migrants, and again on the basis of their sexual identity. “Their relationships with their compatriots or other guests of the camps are sometimes problematic,” Neri explained. “Even when they are advised to seek help from local groups or associations, asylum seekers themselves make it clear that they are not going to take steps in that direction as long as they are living in the camps out of the fear of being exposed as gay to the other refugees”.

According to the UNHCR Global Report, LGBTI asylym seekers and refugees are subject to “severe social exclusion” and violence in countries of asylum by “both the host community and the broader asylum seeker and refugee community.” The document added that “while the degree of acceptance of LGBTI persons was reported as very low in all accommodation settings, the lowest degrees of acceptance, across all respondents, were noted in camp settings.”

Foto: LGBTI Migrants Solidarity Rally – mathiaswasik (CC BY SA 2.0).

In order to tackle these problems, a shelter for LGBTI refugees was recently opened in Berlin by the gay rights organisation Schwulenberatung with a capacity of close to one hundred people. The project leader explained that the shelter was created to protect its guests from the violence and discrimination taking place in the camps: between September and December 2015, about 95 attacks were reported, mostly at the hands of other migrants.

A similar shelter was due to open this spring in Bologna, following an initiative by the Movimento identità transessuale (MIT), which over the last few years has been helping several LGBTI migrants who had denounced discrimination and violence in the reception centres. The project, called “Rise The Difference”, is currently in limbo because the UNAR funding has been frozen following a report from the TV show Le Iene, in spite of a pre-existing agreement with Mediterranean Hope to fly in two Lebanese citizens (who were arrested for being transsexual) via a humanitarian corridor. Also operating in Bologna is MigraBo, founded in 2012 by a network of associations with the aim of helping LGBTI people in their asylum applications.

The issue of integration in the case of LGBTI asylum seekers requires a double effort, considering that even the homosexual community is not immune to episodes of racism and suspicion. Dell’Amico explains that Arcigay’s work with migrants actually originated from research on “multiple discriminations”: being shunned by one’s community as gay, and being shunned by other gay people as foreigners. “This,” he adds, “is certainly an issue that hasn’t been dealt with enough. Many young people have difficulties and are missing some of the things that happen in other groups. To be clear: a gay asylum seeker from Nigeria is unlikely to find support in his community of origin, but he will often be met with diffidence and suspicion even by the gay community in the host country.” The result is a condition of isolation.

According to Dell’Amico, the first step to ending such isolation is to “start with local groups: expand the network across all of Italy and raise awareness on these topics. Of course LGBTI groups are not representative of the entire homosexual community, but introducing young foreigners into the existing local community is a good way to start.” The second issue concerns the operators in the centres: they must be trained and equipped with the tools to deal with the challenges such people face, including discrimination at the hands of other migrants.

Finally, it is not a bad idea to think of specialized facilities; not ghettos, but safe spaces for people in search of protection. Arcigay, Dell’Amico adds, is going to open an apartment for LGBTI asylum seekers in Modena: “The idea is to reserve some places for them, and some for Italian gay kids who might have been kicked out of their homes. We want to bring Italians and foreigners together, in recognition of their respective issues, because homophobia is something that exists in the world, and in Italy too.”

Translation by Francesco Graziosi. Proof-reading by Alexander Booth.

Header photo: Wikimedia Commons.