An analysis of the legal discipline of the treatment of third-country nationals is bound to be based first and foremost on the so-called Dublin III Regulation (Regulation 604/2013).

The Regulation entered into force on the 1st of January 2014, setting down the criteria and the mechanisms of determination of the member State in charge of examining the request of international protection presented by a third-country national or by a stateless person in one of the European states.

This basically means that the Dublin III Regulation defines which State has the obligation to evaluate the asylum request presented by people who arrive in Europe. Let’s look more closely at the reasons why this happens and how the system works.

The general principles

The European Union has been trying to build up a common asylum system since 1999.

Nevertheless, people arriving in Europe today are still not allowed to choose the State where they are to present their asylum requests. The founding principle of the Dublin III Regulation is indeed that each asylum request has to be examined by one and only member State and this competency is generally attributed (with some exceptions) to the State which played the most significant role in the phase of the first arrival of the individual in the European Union area.

To sum it up: the asylum request by a third country national is to be presented in the first European country the person arrives in – usually, either Italy or Greece – and where he or she was identified by local authorities. This evidently means that individual preferences – that is, where people arriving into Europe actually want to go to and where do they wish to live – are bound to not be properly taken into account.

How does it work?

There is a central data bank – Eurodac – where data and fingerprints of all people entering European states and presenting asylum requests are registered.

In short, this data bank allows to easily trace back in which State the first entrance of each and every person took place; the person is then identified and can present an asylum request. Even in cases where identification does not take place and asylum requests are not presented, as often happens nowadays in Italy, a ticket train or a receipt can be used to prove where the first entrance actually happened.

This means that in all the cases where there are doubts on which State is competent for a given request of international protection, the proceedings are suspended by a so-called “Dublin phase” of assessment. Once the state of first entrance is determined, the authorities of the state where the request was presented ask the authorities of the competent state to take charge of the situation and proceed to transfer the concerned individual to their hands.

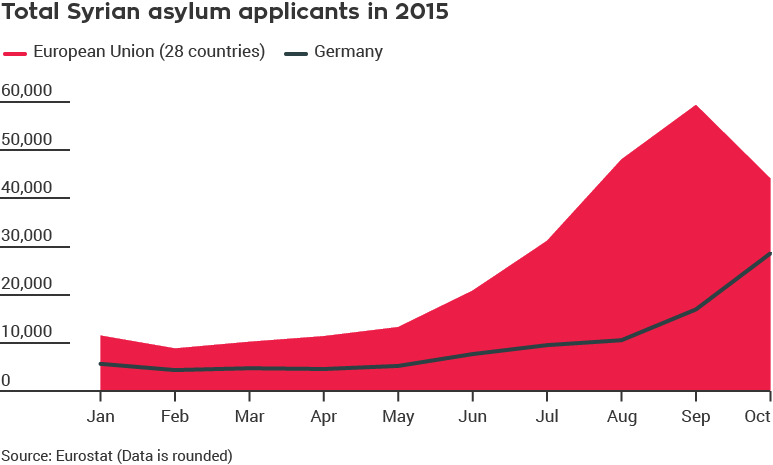

The member State who is defined as competent is obliged to take into account the request of protection presented in another state. E.g.: an undocumented third-country national who arrived in Italy but presented his asylum request in Germany has to be transferred back and have his case evaluated by the Italian authorities.

Limits

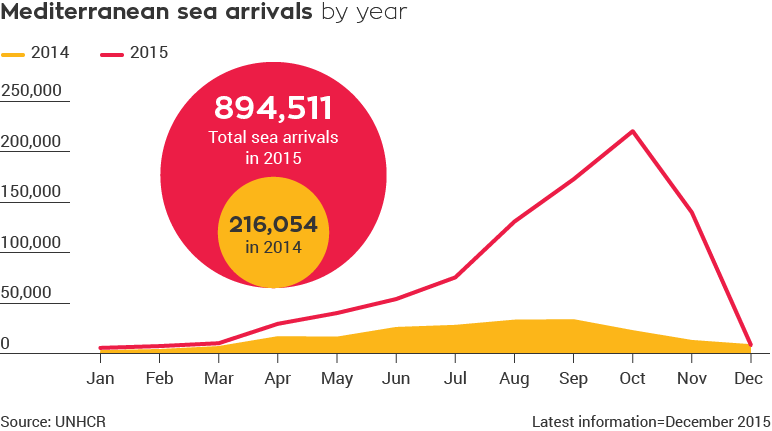

This implies that persons arriving in Italy, Spain, Greece and Hungary – to mention some of the points of entrance into Europe – have to be lucky enough to not get caught while travelling to the country they ultimately want to settle in.

Following a somewhat perverse logic, the States who save people at sea are then bound to take in those persons and grant them protection; at the same time, people who are saved at sea get no choice in determining where they will live and build their future.

At the current state of affairs, a person who is accorded international protection by a European state is then obliged to live in that country, as she is allowed to travel through Europe only for a limited amount of time – that is, three months – she cannot settle down in other countries neither for work or study reasons.

In practice, someone who gets recognized as a refugee in Italy has no such status in Germany or Sweden: exceptional cases aside, the State competent to examine the asylum request according to the Dublin III Regulation is indeed the one and only state where the future refugee has the right to live in. The current boundaries of the European Union thus do not allow for the application of the principle of mutual recognition and beneficiaries of international protection are not granted freedom of residence in Europe.