At 10 AM, it feels like the day is already over: the north coast of the island of Lesbos is all winter light and haze-free horizon. While our Seawatch boat approaches the Skala Sikaminias harbor, we turn back to the Turkish coastline, barely ten kilometers away across a blue strip. The Sikaminias beach is famous for its pile of life jackets, abandoned by people as they reach the island; we go there to take a break after spending the morning patrolling this stretch of the Greek coast, where 49,958 people have arrived since January 1st 2016 alone (UNHCR data – updated on February 19th).

We started early, leaving the small Molyvos port at dawn: there are Doctors Without Borders rafts generously provided by Greenpeace activists, Catalan Open Arms volunteers, the Frontex boat. Everyone looks for his or her fragment of sea to watch over, waiting for the Juliet radio station – which observes from the hills just outside the city – to announce the coordinates to steer to.

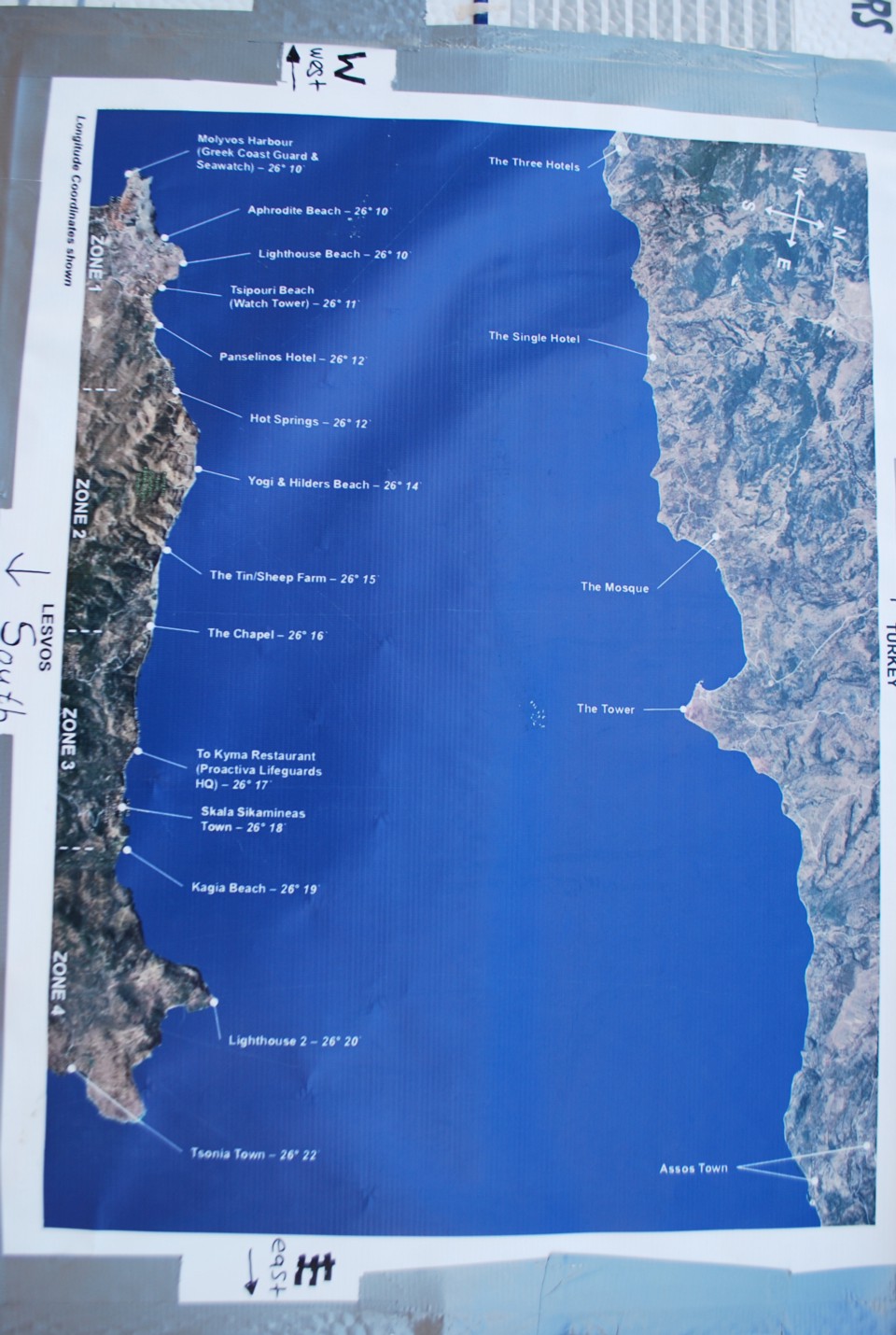

The map of Turkish and Greek coasts, with longitude and latitude coordinates

Day after day, the border between Turkish and Greek territorial waters turns into an oscillating theater where stories have started resembling one another far too quickly. Europe is right there, a stone’s throw, just a few minutes away – one can hardly wait to reach it, but must. It is right there, with all of its promises, but doesn’t dare raise its welcome above a whisper, because it knows the whole story and does not wish to fuel already strained hopes.

A rubber boat full of Iraqi’s refugees (photo credit Federica Mameli)

Because as one more boat reaches Lesbos – and 50, 60, 70 people miraculously disembark, safe and sound, after being stuffed on a raft that had a maximum capacity of 10, their journey in the hands of unprincipled traffickers finally about to end – what happens on this beach in the Aegean Sea?

Skala Sikaminia: just arrived from Turkey, a child receives some gifts from the volunteer

And most importantly, how much do we know and how much should we find out about a journey that we in Europe have perhaps stopped wondering about, because we prefer thinking about a solution for us, and therefore only for the people who already made it here? Staying in Lesbos for one week is certainly not like experiencing that journey in person, but is enough to get a better grasp of how the situation is handled, and a few op-ed for small ways in which we could make conditions more acceptable for those who arrive here.

Starting from the waters that separate Greece and Turkey and going through disembarkation, registration process, reception and relocation, we believe there is room for improvements. Because all countries, and not just Greece, share a responsibility to uphold fundamental human rights.

1. Humanitarian corridors

83,201 people have arrived by sea since the beginning of 2016, but 411 died (IOM data, up-to-date as of February 19th): while the calendar spells out the inconclusiveness of fragmentary European policies, people continue to run away from war and persecution at the risk of their own lives. There were two shipwrecks just during the week I spent in Lesbos, and the delay in rescuing passengers caused 50 victims (16 of which children). Almost all migrants chase the same mirage: asylum and humanitarian protection (1,294,000 requests in 2015, according to Eurostat). Now, many demand humanitarian corridors where asylum may be sought directly at the institutions present in third countries such as Turkey. People will still have to run away from war, but at least will do so without having to get on a boat to face such a dangerous journey.

Last December, Italy launched its first humanitarian corridor project: now 1,000 migrants are expected to arrive over two years, thanks to an agreement signed by the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy (FCEI) and the Community of Sant’Egidio with the Ministries of Interiors and Foreign Affairs. They are considered “extremely vulnerable”subjects and will enter the country thanks to “humanitarian protection” visas. For now, only one Syrian family – father, mother and two children – has arrived: the process was sped up for them because the little girl, Falak, is ill and needed urgent hospital care. They were received by associations and a few sponsors, their expenses covered not by the Italian government but mostly by the Tavola Valdese’s “eight per thousand” (donations collected from Italian taxpayers, who can assign 0.8% of their income tax return to a religious organization of their choice – translator’s note) and private funding from the Community of Sant’Egidio.

I have seen in what conditions migrants arrive by sea: Europe must, without a doubt, adopt a humanitarian corridor policy as soon as possible, making an effort to overcome any disputes among States and trusting countries that don’t belong to the EU. The stakes are too high to continue postponing this solution.

Molyvos

2. Moving past Dublin

One of the biggest obstacles in managing migrant flows in Europe is the Dublin III Regulation. The convention was signed by European countries in Dublin in 1990 and came into force in 1997 (with subsequent amendments in 2003 and 2013), setting a series of rules on the management of migrants who claim asylum in European countries as well as some shared standards for refugee reception. The rules revolve around two key points: firstly, a refugee’s asylum request is under the responsibility of the country where his or her close family resides legally, or where he or she has already been issued a residency permit. Secondly, however, in the absence of ascertained family ties, request and reception become duties of the first country where the refugee set foot.

This process obviously yields a few issues: “border” countries like Greece and Italy, where most migrants arrive at first, end up bearing the responsibility of most identification and asylum requests. This is why most refugees enter the European Union illegally, without the required documents: they are trying to avoid identification in the first country where they arrive, hoping to reach and ask for asylum in wealthier nations in Central and Northern Europe. Of all the people I talked to in Lesbos, nobody wanted to stay in Greece, and almost everyone was hoping to move on to Germany or Scandinavia. If we allowed for identification before migrants reached the country where they want to apply for asylum, reception and integration could be planned beforehand, through perfectly legal – and most importantly safer – procedures.

Today, an ultimatum for Greece to improve its border controls is being discussed, but we should also make sure – as many have suggested – that all countries do their part, without any tricks on numbers and quotas.

As director of Human Rights Watch’s refugee program, Bill Frelick stated last September, the “first country” rule should be revised: “the rule for assigning responsibility for examining asylum claims ought to be based on the country of first application, rather than the country of first arrival. Dublin currently allows this as an exception for unaccompanied children. The exception should be the rule. But this would only work if accompanied by a system for sharing responsibility among EU member states, so that the most popular destinations did not bear a disproportionate burden.”

3. Relocation and collaboration between countries

This point ties in with the previous one, because it’s again a case of collective responsibility for all EU member States. Migrant relocation quotas exist, but are not abided by. Last September, European countries agreed to relocate 160,000 refugees over two years – 40,000 as part of a voluntary reception system approved in June and 120,000 “imposed” to the various countries according to set quotas. However, today only 272 migrants have been relocated: 0.17% of the total that had been agreed on, and only 0.03% of the 1,008,616 migrants that came to Europe in 2015. A number of countries backed out, and Greece – between financial problems, a pension system reform up in the air and crippling strikes (three days without ferries between Mytilene and Athens wreaked havoc in the entire system) – lives on the brink of collapse. In particular, a great risk is posed by the fact that the border with Macedonia could be closed, as has been already announced many times.

The situation in Macedonia grows more dramatic every day. The government has started building a second barbed-wire barrier along the border with Greece, 5 meters from the existing fence: a measure to block the flow of migrants who, after arriving in Greece, head to the Balkans on their way to Central and Northern Europe. Conflicts between migrants and the policemen who patrol the border are reported every day, and the Idomeni camp in Northern Greece, 25 kilometers from the Macedonian border, is increasingly crowded. The winter is ice-cold in the area, and Save the Children has recently denounced the terrible conditions in which refugees, and especially children, have to live: “In Idomeni, on the Greek border with Macedonia, [where temperatures drop way below zero], the authorities have blocked access to a transit camp where aid agencies provided heated tents and food to refugees. Families are now being forced to sleep outside at a nearby petrol station with no shelter”.

There are 51 tents set up by the UNHCR in Idomeni, with a total capacity of approximately 1,000, but the flow of people coming in gives no sign of slowing down. This poses two risks: overcrowding the camp, and fueling the existing “business” of clandestine crossings, managed by organized crime. Recently, some have suggested requiring that migrants at the Greek-Macedonian border show not only the documents issued by the Moria “hotspot” to attest their country of origin, but also personal ID to prove their actual nationality. Should this measure become effective, the additional requirements would only foster the market for personal documents and increase the number of “rejects” – who would be taken back from Macedonia to Athens only to try to cross the border again, this time on foot and with help from the local mafia. When the legal way becomes too difficult, desperation pushes people to find different solutions.

4. Interpreters and guarantees

During “safe” disembarkations with the assistance of the Coast Guard or Frontex, migrants are left to wait on the pier so that the Coast Guard can register them. They form lines depending on their origin and language, then start a slow and difficult dialogue with the agents – because there are no interpreters, only volunteers who speak Arab and a few migrants who speak a little English to help out. The problem is not only the time it takes to understand each other, but also the lack of any guarantee that what migrants declare will be translated and interpreted correctly. Precision in gathering their personal data is crucial to decide their destiny: Imran, an Afghan teenager I met in Moria, told me that during registration he listed some of the countries where he lived before deciding to come to Europe.

Because he mentioned Iran, and because he was misunderstood, his documents stated he was Iranian: a mistake that – if he had not had it corrected – would have exposed him to the risk of deportation: in fact, the current hotspot system tends to evaluate asylum claims very superficially and considers nationality as a key parameter, without taking into due account the specificities of the single case. Many European states are indeed now letting in only people coming from Iraq, Afghanistan and Siria, who appear to be considered as the only legitimate asylum seekers. This is especially problematic as it means people arriving into Europe are not correctly informed about their rights and their potential eligibility for international protection.

How many similar mistakes are made every day, due to lack of time and qualified interpreters or legal counselors who can explain the consequences of certain declarations? For example, migrants who declare they are coming to Europe to work – as might be considered quite natural – are considered “economic migrants”, and as such are rejected. In this situation, people’s right to be informed is constantly infringed. The data and information gathered by the Coast Guard in these less-than-perfect conditions might even be handed over to Frontex to speed up the official registration procedures: although we cannot know for sure, we would not be surprised if that was the case, also because the Moria hotspot has often been criticized for being too slow, and I have personally seen Coast Guard agents hand lists of data they had been gathering to Frontex officers. Is this the standard of control we want to uphold at the border?

5. Safety

Safety is an issue for migrants as for people who already live in Europe. The tragic events in Paris on November 13th 2015 and what happened (or did not happen) in Cologne last New Year’s Eve are a stark reminder of how fear can be amplified, spread and blamed on people who are “guilty” of nothing but sharing terrorists’ country of origin. The more we can guarantee refugees their rights to be informed and to have legal protection, the easier it will be to control their origin, personal information and documents. However hard it may be in this time of unbridled populism and made-up threats and disasters, we need to establish a relationship of trust with migrants. They must know that they will be protected once they reach our shores, and that their rights and obligations will be explained to them. We must cut any ties they may have with clandestine immigration, which only on the route to Turkey makes approximately 3 billion euros a year for organized crime. We cannot rely solely on barbed wire fences, if we truly want to fight migrant smugglers.

A Hellenic Coastguard ship rescues a rubber boat and a wooden boat in front of Lesvos island, during an operation called Fast Track

6. Minors

You don’t notice them immediately, when you look at a boat coming to Europe: all you see are adults, usually men. That’s only because women and children are sitting inside for their safety. You see them only once the raft approaches the coast, or when passengers start disembarking. According to Eurostat, the European agency that has recently published definitive figures for last year, almost one third of the refugees who arrived in EU countries (plus Norway, Switzerland and Iceland) are children and teenagers. It’s a huge number of minors, not always traveling with their families: some 25,000 of them are alone (2015 data), with a very high risk that they are victims of trafficking. It’s hard to find out, given the conditions: on particularly busy days, when a lot of migrants arrive at once, the Coast Guard doesn’t have the resources to make sure each and every minor has someone to protect him or her. Furthermore, no special assistance is provided to them, if not by volunteers from organizations such as Save the Children, who try to make arrival less traumatic for them. In its 2015 Multi-sector Needs Assessment of Migrants and Refugees in Greece, Save the Children has stressed the existence of a very high risk of exploitation, abuse and illnesses, sometimes even deadly, caused by the collapse of the official reception system due to the economic crisis. Let’s not forget that minors, even when they have entered a country illegally, are protected by the 1989 New York Convention on the Rights of the Child (other sources on the situation of foreign minors can be found at this link.)

7. Money

Outside the Moria camp, the business revolving around migrants is obvious: you can buy SIM cards, blankets, food and “all inclusive” ferry and bus tickets for what is described as a safe ride from Mytilene to the Macedonian border. Services inside the camp are free, of course, but are not always sufficient. You have to pay even to take the shuttle bus from Moria to Mytilene, which belongs to the municipality and was once used for tourists. Migrants have a long journey ahead of them and are already deep in debt – they will often have paid their way here through hawala, a system based on trust dating back to the Middle Ages, which makes tracing money impossible. It is estimated that 90% of migrants who arrive in Europe have used the system, transferring 390 billion euros to smugglers every year.

The word ḥawāla literally means transferral. And here is how it works: money gets transferred through a network of mediators. A client approaches a broker, called hawaldar, and gives him an amount of money to be transferred to a person in another city or another state. The hawaldar furnishes a secret password to the client, who will pass it on to the person who is supposed to receive the money. The broker calls his counterpart – that is, another hawaldar – in the city where the money are to be delivered, gives him indications on the transferral and takes on the obligation to refund him. From that moment, the beneficiary can contact the second hawaldar, give him the secret password and receive the money. The main characteristic of the system is that brokers do not provide each other guarantees of any kind: transactions amongst them are based exclusively on honour. Every transaction is informally registered in order to keep track of debts and credits, but that’s it.

To effectively fight clandestine immigration, as many have stated is in their intentions, there is no better way than to create a safe and legal way to reach Europe. At the moment, traveling from Afghanistan to Turkey can cost 3,000 to 6,000 euros, depending on conditions. “Some can afford a ride on a car stuffed with ten other people, others can pay more to travel more ‘comfortably’,” says Ahmed, an Afghan boy I met outside a travel agent’s in Mytilene that sells tickets to Athens (95 euros to reach the Macedonian border). It’s easy to imagine that once they reach Europa, migrants don’t have much money left. Some supplies are provided by the UNHCR (food and medicines), but most come from donations (there seem to never be enough dry clothes). It is crucial that the EU make a greater investment in reception systems, to avoid making a situation of extreme vulnerability even harder.

8. Conditions at migrant camps

We will come back to Moria and the conditions at the only hotspot currently open in Greece in a future article. For now, suffice it to say that despite the presence of the UNHCR and other NGOs, the place where migrants are transferred upon arrival is far from welcoming. Its capacity of 400 people is absolutely insufficient: on average days, when between 800 and 1,000 people arrive, there are over 2,000 inside the camp. Meanwhile Kara Tepe, another camp near Mytilene that is mostly used for Syrian refugees and their families, is almost always empty – probably because it is not a hotspot. When we were in Moria, although the weather conditions in Lesbos were good and it had not rained for a few days, it was extremely difficult to find a dry corner where to sit down. All in all, it looked like a makeshift camp with tents unfit even for a simple camping trip.

Moria refugee camp, the external part (photo credit Federica Mameli)

Registration queues are very long, and people sometimes spend the whole night outside – even under the rain – because the process is supposed to be ongoing (carried out by Frontex during the daytime, and by the Greek police at night). Volunteers have set up another camp outside Moria to help bridge the gap in available space and resources. Once formally identified, refugees are given a ticket that allows them to move around even outside the camp, while they wait to be transferred to the harbor. Their stay varies in length, also depending on how many new arrivals there are and on whether it is possible or not to leave from Mytilene. Usually it takes two or three days, but ferries to Athens often go on strike and leave people stuck here for up to a week. The health and sanitation conditions are unacceptable, and information relies more on word of mouth than official and well-coordinated sources. Europe is giving a very poor first impression to the people it is supposedly welcoming.

Afghan people, arrived the day before, forming a queue for the registration in Moria camp

9. Transparency

Why registration procedures cannot be more transparent is not clear. At Moria, they are carried out in two separate areas (depending on the language), fenced off from journalists and lawyers. We often asked whether legal counselors were present to explain to migrants their rights and the process to apply for asylum or international protection, but were told they were not necessary because “Frontex takes care of everything”. However, in the last few weeks, the First Vice-President of the European Commission Frans Timmermans, based on the data contained in a Frontex report yet to be published, stated that approximately 60% of migrants registered in December were economic migrants.

This is surprising because, according to the UNHCR’s daily updates on migrants’ nationality, of the 85,000 refugees who have reached Europe since January 1st 2016, 45% were Syrian, 29% Afghan, and 17% Iraqi. Meaning the large majority came from war zones, and would certainly not be expected to be economic migrants. Where does the truth lie? If we had more transparency, upheld migrants’ right to be informed, and allowed legal counselors and external observers further access, the EU would have more reliable data on arrivals as well as on the practical difficulties in current registration procedures, during which – as we have heard from a number of people – not having translators and cultural mediators available is detrimental.

10. Coordination

David is 38 years old and was born in Singapore but lives in Canada, where he works as security manager for a major company. He came to Lesbos last month as a Starfish Foundation volunteer. The fact he speaks Arab makes him invaluable, especially during disembarkations. “We try to cooperate with the authorities as much as possible, but it’s not always easy. They need us but often don’t trust us, and not having an official role in aid processes obviously makes us appear less accountable to them. There is no institutional coordination: who decides who is responsible for what? Who does anyone answer to?

Acting simply out of common sense and experience is not always the best idea, because roles end up overlapping and issues come up and delay our efforts. When we do find someone who is willing to listen and coordinate with us, everything has to be completely off the record. This causes a number of problems, also because many volunteers come to Lesbos with good intentions but no solid training. If we had an official register and well-defined roles, they could be sent to other locations or could be managed more effectively, according to their individual skills.”

Twitter: @MarikaS

Note: this article has been edited in the sections referring to humanitarian corridors (in order to correctly specify the subjects involved in the pilot project) and to interpreters & guarantees (to better clarify the functioning of legal procedures).