The Trump administration’s latest travel ban is back in U.S. federal court. The Fourth Circuit, based in Virginia, and Ninth Circuit, based in San Francisco, are hearing cases challenging the latest executive order banning immigrants and refugees from six Muslim majority countries from entering the United States. Joining the fray are 162 technology companies, whose lawyers collectively filed an amicus brief to both courts. Amazon, eBay, Google, Facebook, Netflix, and Uber are among the companies urging federal judges to rule against the executive order, detailing why it is unjust and how it would hurt their businesses.

While the 40-page brief is filled with arguments in support of immigration, it hardly speaks about refugees, except to note that those seeking protection should be welcomed. Any multinational company with a diverse workforce would be concerned about limits to international hiring and employee travel. But tech companies should also be concerned about the refugee populations that depend on their digital services for safety and survival.

In researching migration and the refugee crisis in Europe, my team and I interviewed over 140 refugees from Syria, and I’ve learned that technology has been crucial to those fleeing war and violence across the Middle East and North Africa. Services like Google Maps, Facebook, WhatsApp, Skype, and Western Union have helped refugees find missing loved ones or locate safe places to sleep. Mobile phones have been essential — refugees have even used them on sinking boats to call rescue officials patrolling the Mediterranean.

Refugees’ reliance on these platforms demonstrates what tech companies often profess: that innovation can empower people to improve their lives and society. Tech companies did not intend for their tools to facilitate one of the largest mass movements of refugees in history, but they have a responsibility to look out for the safety and security of the vulnerable consumers using their products.

Some tech companies have intervened directly in the refugee crisis. Google has created apps to help refugees in Greece find medical facilities and other services; Facebook promised to provide free Wi-Fi in U.N. refugee camps. A day after President Trump issued the first travel ban, which initially suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, Airbnb announced it would provide free housing to refugees left stranded.

Notable tech leaders have spoken out against policies that turn away refugees. Soon after the ban, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote on his personal page, “We should also keep our doors open to refugees and those who need help.” He noted that his wife’s family came to the U.S. as refugees. Brian Chesky, CEO of Airbnb, tweeted, “Not allowing countries or refugees into America is not right, and we must stand with those who are affected.” And Google cofounder Sergey Brin joined the protests against the executive order at San Francisco International Airport, saying, “I’m here because I’m a refugee.” (He later said that he and his family fled oppression in the former Soviet Union.)

These efforts to directly help and advocate for refugees have been admirable. But collective action from the tech sector would be more effective for swaying the opinions of the courts and the public. The amicus brief would have been the best opportunity for an industry-wide statement that the government should welcome refugees, particularly those who have already cleared stringent security checks to enter the U.S.

A stronger stance would be in the companies’ best interest. Corporations are facing greater pressure from their employees and customers to take a stand on political issues and uphold certain values. As Ken Shotts, professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business, told me, “Many employees (U.S.-born as well as immigrants) expect tech companies to live up to their grandiose claims about values and doing good in the world. Unlike employees in most companies, they have leverage, due to the tight labor market in Silicon Valley.”

Consider how, a few days after Trump’s first travel ban, thousands of Google employees walked out of their jobs in a day of protest. Consider, too, how Uber suffered a PR crisis for seeming tone-deaf immediately following the ban. Despite CEO Travis Kalanick’s statements in support of immigrants and refugees, many Uber employees and consumers were furious that he still planned to attend Trump’s meeting of economic advisors a few days later. In the wake of the #DeleteUber campaign that followed, Kalanick stepped down from the advisory council.

In recent years technology companies have tried to convey to the public that they will protect their consumers against government overreach. For example, Apple has refused to give government authorities a backdoor key to encrypted iPhones, and Microsoft recently won a federal case wherein it refused the U.S. government’s demands to hand over consumer data stored overseas.

The sector should extend these efforts by making sure its technologies aren’t used to target broad groups of people based on nationality or religion. Already the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CPB) is asking for the social media accounts — even passwords — of visitors from other counties. The Council on American-Islamic Relations has filed complaints against the CPB, stating that Muslim American citizens have been subjected to enhanced screening that includes scrutiny of their social media accounts and cell phones.

Trump has talked about creating a database to identify and register Muslims in America, including refugees. A number of companies, including IBM, Microsoft, and Salesforce, have stated they will not help build a Muslim registry if asked by the government. In addition, a group of nearly 3,000 American tech employees signed an online pledge promising they would not develop data processing systems to help the U.S. government target individuals based on race, religion, or national origin.

Tech companies need consumers’ trust now more than ever. Deserved or not, tech is getting blamed for an array of societal ills, from social media perpetuating fake news to artificial intelligence taking away jobs. Trump’s executive order will likely be challenged in other high-profile cases, giving companies an opportunity to highlight how their innovations help refugees fleeing conflict. The industry can use future amicus briefs to make stronger collective arguments to the courts and to the public. In speaking up for the most vulnerable members of our global community, the tech industry would send the message that it cares about more than the bottom line.

This article has been originally published on the Harvard Business Review and is here reproduced for kind permission of the author.

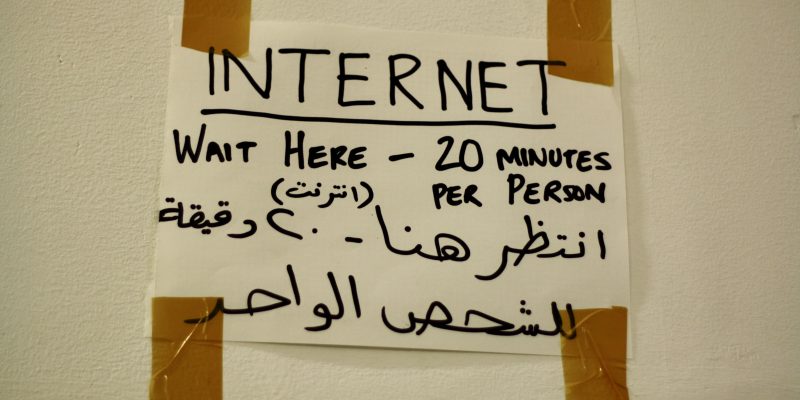

Header photo: Internet space in Milan’s hub (photo by Marina Petrillo).