1. The Salvini decree is not retroactive

The new and more restrictive norms on humanitarian protection introduced by Italy’s security decree do not apply to requests lodged before October 5, when the bill was approved.

The decision from the Court of Cassation came after hearing the appeal of a Guinean national, whose application had been rejected by a Naples court. The ruling said that applications lodged before October 2018 must be examined under the prior rules.

As Il Fatto Quotidiano reported, pre-existing applications will be examined under previous criteria on humanitarian visas, and all permits issued will be marked as “special cases” (per the new decree) with a validity of two years, after which the new rules will apply.

Recognition under the new criteria dropped to a record 2% in January; an increase in appeals is expected following the ruling of the Supreme Court.

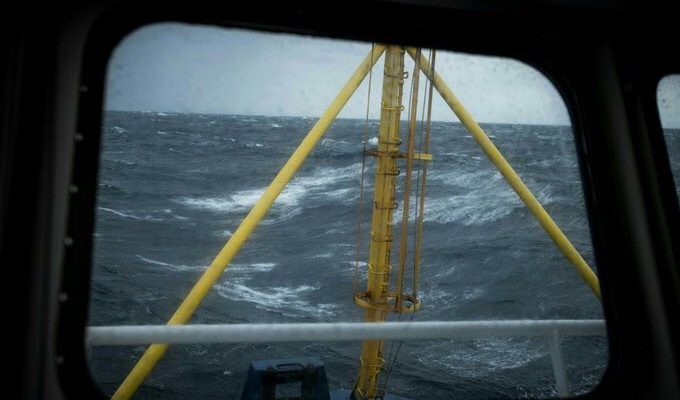

2. Italian interior ministry denies that Minister gave order blocking Sea Watch

The ports are closed, the ports are not. Matteo Salvini never gave the order to block the ship Sea Watch from docking in Catania, where 47 migrants had been disembarked on January 31. Neither did the Italian interior minister veto the disembarkment of minors when the ship was in Syracuse. All this, – as Nello Scavo wrote in Avvenire – despite the deputy PM’s repeated insistence that “Italian ports are closed”. Official documents proved the contrary. In response to an inquiry, the immigration division of the Department of Public Security said that the ministry “has not issued and does not keep record of any order or communication transmitted to the ship Sea Watch”.

The migrant rescue ship was allowed to leave the port of Catania only yesterday, after being held for three weeks.

Meanwhile, Welcoming Europe, the campaign speaking out against the criminalisation of solidarity and calling for humanitarian corridors and a heightened awareness of victims of abuse at borders, has collected 65,000 signaturesin Italy, more than 10,000 over the required minimum.

3. Libya unsafe according to Italian foreign affairs ministry

Why are 700,000 people being held prisoners in Libya? Because they are like cash machines. Roberto Saviano writing in l’Espresso explained in no uncertain terms why Libya is not a safe country: “Migrants trying to reach Italy via Libya are a business opportunity as soon as they set foot on Libyan soil. They and their families are being extorted money when they are promised an easy, swift journey in their countries of origin, and when they become prisoners in Libya, when they take to the sea and even when they are sent back to Libya, for the cycle to start again.”

Migrant arrivals in Italy, according to reports from Voci dalla Libia, have not droppbed thanks to Italian policies, but because migrants in Libya are source of lasting profits.

Latest @TIME on how refugees in Libya, Sudan & Niger are turning to Facebook to crowdfund ransoms, as smugglers hold them hostage & torture them until they pay inflated rates.

Sorry for the graphic images, but these are being posted publicly & regularly.https://t.co/dF8bw40hRT pic.twitter.com/EGU6FkYqi3— Sally Hayden (@sallyhayd) February 6, 2019

Meanwhile, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs itself appears to not regard Libya as a safe country: non riconoscere la Libia come un paese sicuro:

“Travelling to Libya is discouraged due to precarious safety conditions in the country,” reads their website.

4. Diciotti migrants to sue Italian leaders for damages

The dust has just settled among the Five Star Movement-League government coalition in Italy over the lawsuit against interior minister Salvini, and the Diciotti case may spark fresh tensions.

Some of the Diciotti migrants, have filed a lawsuit in a civil court in Rome, seeking damages from the Italian government for being held aboard the ship for several days. According to newspaper reports, the suit was filed by a law firm on behalf of 41 migrants, including a minor, who were on board the ship, and who are now seeking between 42,000€ and 71,00€ in compensation from PM Giuseppe Conte and interior minister Salvini. The suit was initially filed before Christmas in a Rome civil court by attorneys from the legal network of the Baobab Experience centre, coordinated by Giovanna Cavallo. A concurrent suit was filed in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The hearing in Rome is expected to take place in the spring.

As Andrea Gagliardi wrote in Il Sole 24 Ore, this is not the first case of the Italian government being sued by migrants.

The interior minister replied promptly: “Allow me to respond with a big laugh. They should not try to fool Italians; the party is over, there are no more migrant boats coming. We might send them a box of chocolates.”

5. The tax on money transfer is discriminatory

The 1.5% tax on money transfer to non-EU countries is “unjustified discrimination”. The Italian Antitrust authority, in a letter to the government, called for

Lo dice l’Antitrust in una segnalazione spedita al Governo changes to the fiscal decree of October 23. According to the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM), the tax would only affect money transfer and not post offices or banks, Italian or otherwise.

The authority also fears consequences for transparency. Transferring money abroad is already subject to “numerous and ever-changing variables, including commissions and exchange rate spread.” The tax would also make “economic terms of service” more opaque.

6. Spain and Morocco reach deal to curb irregular migration flows

Spain and Morocco have reached an agreement on an unprecedented strategy to contain irregular immigration, Under the deal, Spain’s sea rescue services, Salvamento Marítimo, will be allowed to take some of the rescued migrants back to Moroccan ports.

The measure is part of the Spanish executive’s attempts to reduce migratory pressure on the ports of Andalusia, where migrants rescued in the Alboran sea have been taken until now.

According to government sources quoted by El Pais, the measure will apply to migrants found in missions where Spanish rescue services are assisting the Moroccan Coast Guard in their maritime area of responsibility, and when the nearest port is in Morocco:

“Given our good relations with Morocco, Salvamento Marítimo will assist the Moroccan Navy if so required. In that event, rescued individuals will be taken to the nearest safe harbour, which in this case will be Moroccan.”

The agreement is yet to be ratified but has already attracted criticism from NGOs, worried that migrants will be denied their right to seek international protection.

According to the Comisión Española de Ayuda al refugiado (CEAR), Morocco is not a safe country for migrants and refugees, since it has not yet passed any law on the right of asylum. “Since late 2017, the Moroccan bureau of asylum has been effectively paralysed”, the organisation said.

7. Border purgatory: Trump administration’s latest effort to deter refugees

Despite the Trump administration’s insistence that asylum seekers enter the U.S. legally, it has rolled out a series of policies at the border that make it nearly impossible for them to do so. Asylum seekers who lawfully attempt to enter the U.S. are being forced to wait in Mexico – or made to leave after gaining entry – even after demonstrating they have a credible fear of returning home, wrote Anne Dutton and Isaac Bloch for the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies.

8. Living conditions and access to education, what future for refugees in Greece?

Unhygienic conditions, lack of food and an especially troubling situation for children: the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) has published a report on the “inhuman and degrading” conditions found during the visit to Greece from 10 to 19 April 2018.

As Valigia Blu reported, the CPT did not fail to notice, as it often has in the past, the need for a coordinated EU approach to address the phenomenon of the high number of foreign nationals arriving in the country.

From conditions in refugee camps to the education system: formally, asylum seekers and refugees have a right to public education, but about half of refugee children are not yet signed up. Emma Willis reported in Info Migrants on the situation in Greece and the efforts from the community to guarantee the right to an education for everyone.

9. Migrant diaries describe hopes and fears of new Italians

“I was born in the wrong time, where there’s little room for the weak and the helpless… I think I can close my suitcase because it used to be full of hope and the need for acceptance. Today I only wish for some sweetness, to take away all the bitterness from many disappointments”. These moving words are from Milivoje Ametovic, who was born Serbia and came to Italy in the 90s seeking new opportunities. Much like many Itailans who left their country decades ago, his story is one of thousands collected and preserved Archivio Diaristico Nazionale in Pieve Santo Stefano, near Arezzo. As Roberta Scorranese wrote in Corriere della Sera, the archive launched a national initiative to gather and publish autobiographical records from foreign citizens.

DIMMI “Diari Multimediali Migranti” collects (and awards) the memories of new Italians. Like Azzurra, who suffered discrimination in her home country for being an albino, or Dominique, who fled civil war and is still awaiting political asylum.

10. Afghan asylum-seeker offers to pay Elin Ersson’s fine

Elin Ersson, the Swedish activist who stopped a plane from taking off with an Afghan asylum-seeker on board, was fined 3.000 kronor (€ 285) by a Gothenburg court for violating Swedish air safety regulations. The fine could now be paid by Arif Talash, a 29-year-old Afghan asylum seeker living in Germany.

Talash is part of a Frankfurt-based group of activists who supports asylum seekers and advisse them on their legal rights. “I am ready to pay the fine imposed on Elin Ersson on her behalf,” he said to Deutsche Welle:

“I heard about Elin Ersson’s story on social media, and I deeply admire and appreciate her efforts.“

Cover photo via Sea Watch Italy