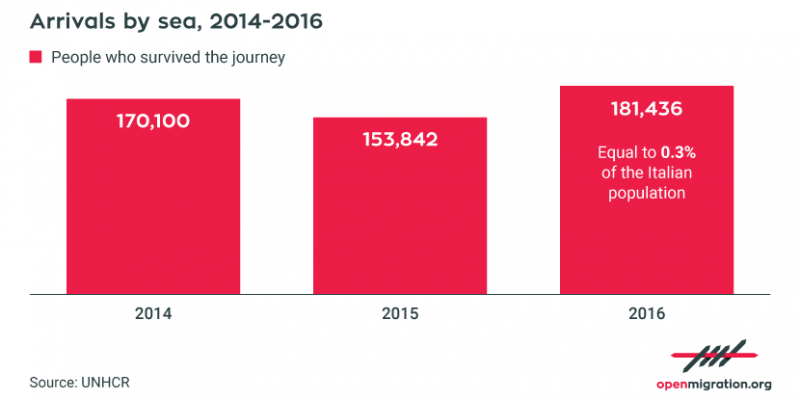

In 2014 there were 170,000 arrivals by way of the extremely dangerous Mediterranean route, in 2015 there were 153,000 and 181,000 in 2016. And though these are rather consistent numbers, they are not at all alarming (at least in theory, seeing as that, in practice, alarmism seems to have become the norm): new arrivals represent just 0.3% of the Italian population, which renders any talk of an “invasion” absolutely inappropriate.

Different stories and routes but with something in common

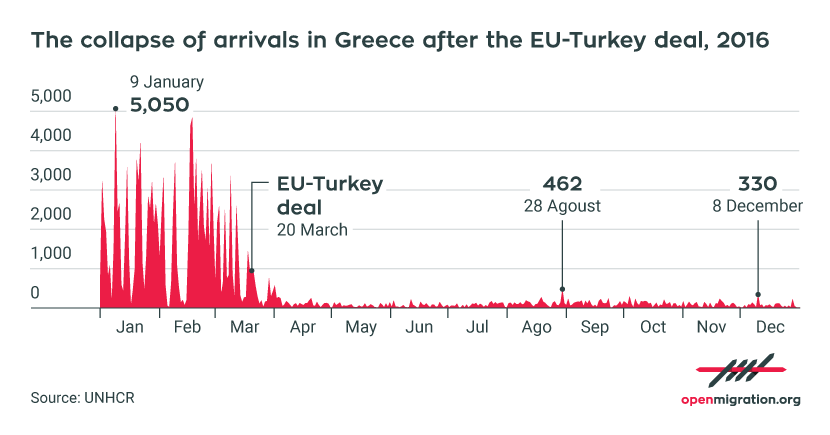

While arrivals in Europe by sea have drastically gone down compared to 2015 – from just a little more than one million to about 361,000 –, on the Italian coast they have remained consistent. But here too it is important to be weary of superficial readings: our country is once again in first place as to the number of arrivals which, in 2015, was held by Greece with its 856,000; nevertheless, this does not mean that there is any “emergency” and has little to do with what is happening in Greece. If so many people are arriving on our shores, it is not a result of the contested agreement with Turkey – which caused, at an extremely high cost in terms of the violation of human rights, a drastic decrease in the number of arrivals on Hellenic shores (856,000 in 2015, 174,000 in 2016) – but, rather, the result of (other) precise European policies (see below).

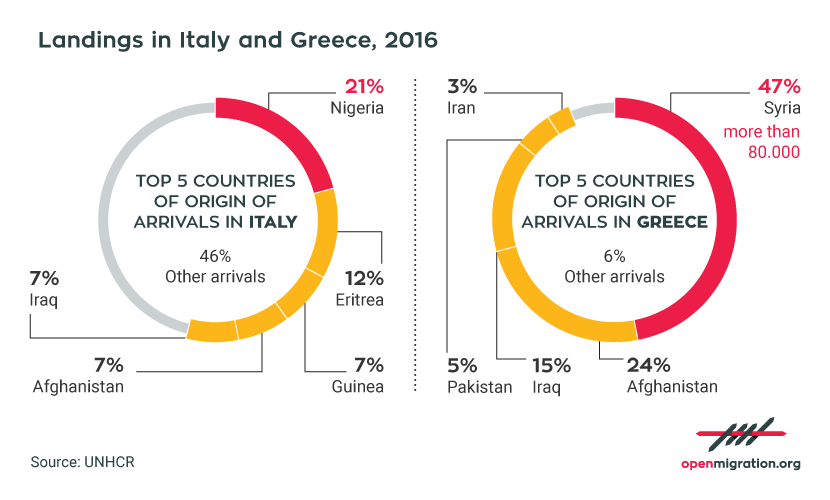

The closing of the Greek route has nothing to do with Italian numbers. The two routes – the central Mediterranean one towards Italy and the eastern Mediterranean one towards Greece – are, indeed, by nature taken by people of various nationalities: according to the latest statistics from the UN agency for refugees (UNHCR), those arriving in Greece are (or would it be more accurate to say were?), above all, Syrians, followed by Afghanis and Iraqis while in Italy they are primarily Africans, mostly Nigerians and Eritreans.

Here too we need to be careful not to fall into simple misinterpretations. Those who say that the people arriving in Italy from the sea “are not fleeing any war, are not Syrians and will never achieve the status of refugees” are grossly and seriously oversimplifying, first of all because it is impossible to hastily settle an asylum request based on the applicant’s nationality – in as much as the right to international protection is a right related to individuals and not their country of origin – and, secondly, because Syrians are not the only ones risking their lives to receive international protection. From an analysis of statistics and concrete cases, one learns that this is what asylum seekers in Italy are fleeing: terrible violence, forced marriage, intolerable discrimination. The reality – says the UNHCR – is that the vast majority of persons who undertake the desperate trip of hope across the Mediterranean are in need of international protection. In other words: different stories and routes, but ones that have something in common.

Libya is the only way among violations of human rights and deaths at sea

There is nothing at all surprising about the migratory flows crossing our sea. The fact that for thousands of Syrian refugees it has become impossible to reach Greece and therefore Europe and that Italy is thus almost the only possible destination for African asylum seekers has to do with clear European political choices. On the one hand the agreement between the European Union and Turkey that has closed the way to Syrians, on the other the construction of a sort of non-physical wall towards Africa by means of the progressive closure of the principal migratory routes (see the Spanish “model”), which – as explained in an article by the journalist Martin Plaut – has made Libya the principle point of departure, and Italy the principle point of arrival for the many Africans fleeing violence, discrimination and terrible poverty.

There is nothing surprising in the fact that almost 90% of the people arriving in Italy began the crossing from the coasts of Libya. And therefore there is nothing surprising either about the dramatic conditions thousands of asylum seekers find themselves in there (there have been denunciations of continuous and grave violations of human rights, even and, above all, including minors) nor in all of the deaths at sea, ever more, and never so many: above all, people are dying on the coasts of Libya and Lampedusa, along the cursed route of the central Mediterranean.

Ever more unaccompanied minors

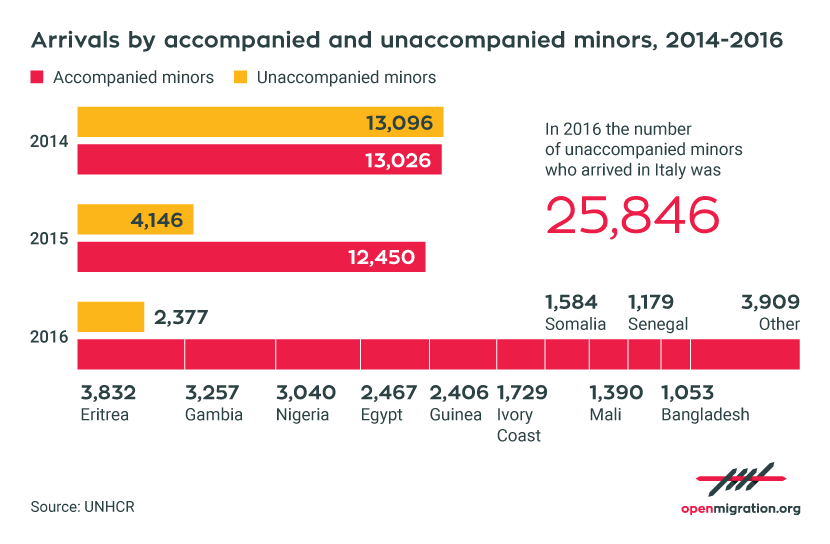

If one wants to talk about an “emergency” – rather than arrivals or asylum requests – then one must talk about deaths at sea. Or about unaccompanied minors (unaccompanied foreign minors – UAM – as they are officially known). Just as there have never been so many deaths at sea, there have never been so many children alone in Italy – here too there is an overwhelming number of Africans. There were about 13,000 UAMs who arrived in our country in 2014, and a little more than 12,000 in 2015; this number almost doubled in 2016 with the arrival of just under 26,000 unaccompanied minors. Up until today, more than 90% of those minors who have arrived in Italy have been left to their own devices.

Here too we encounter a consequence as predictable as it is troubling: thousands of minors arrive in Italy and “disappear” from the reception system – though often victims of exploitation, even more frequently they have been driven (one could also say “forced”) to disappear by the dysfunction and bureaucratic red-tape related to applying for asylum, gaining access to work and being reunified with their families. In short, there is a hole in the system that swallows thousands and thousands of unaccompanied minors. According to the most recent statistics, in Italy at the end of 2016, there were around 6,500 untraceable UAMs.

In conclusion, Europe is continuing to make a mess of everything with its policies on immigration – closing its doors to refugees, forcing asylum seekers to undertake ever more desperate and deadly trips, abandoning minors to themselves —, and it is doing so in spite of the dramatic evidence of numbers. And we cannot but ask ourselves when we will begin to learn the lessons of history written down in black and white on the page.

Translation by Alexander Booth.