“Coronavirus? Us from Africa, we are immune”: Makan, 21, jokes about it. And thinking about it, since he left Mali – his home country – four years ago he has been through way worse. At the end of 2018 he obtained humanitarian protection: that should have been good news, a starting point. Instead, in the span of two weeks he was literally left on the street; the first Security Decree signed by the former Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini cancelled humanitarian protection and determined expulsion from the reception network for those holding such permit.

Makan found an emergency accommodation in Intersos’ dorms, in Rome, thanks to a friend. After a couple of months he found a job and a room for rent, both off the books. But without a regular lease Makan was not entitled to civil registration, and without a work contract he could not convert his humanitarian protection into a work visa. Two months ago he lost his job and he ended up on the streets again, near Tiburtina railway station.

“WE HAVE BEEN SELF-REPORTING FOR THREE WEEKS”

The entrance to the station on Piazzale Spadolini has been a make-do shelter for hundreds of migrants for over three years now: they sleep on the sidewalk, on a piece of cardboard, with a sleeping bag or some blankets.

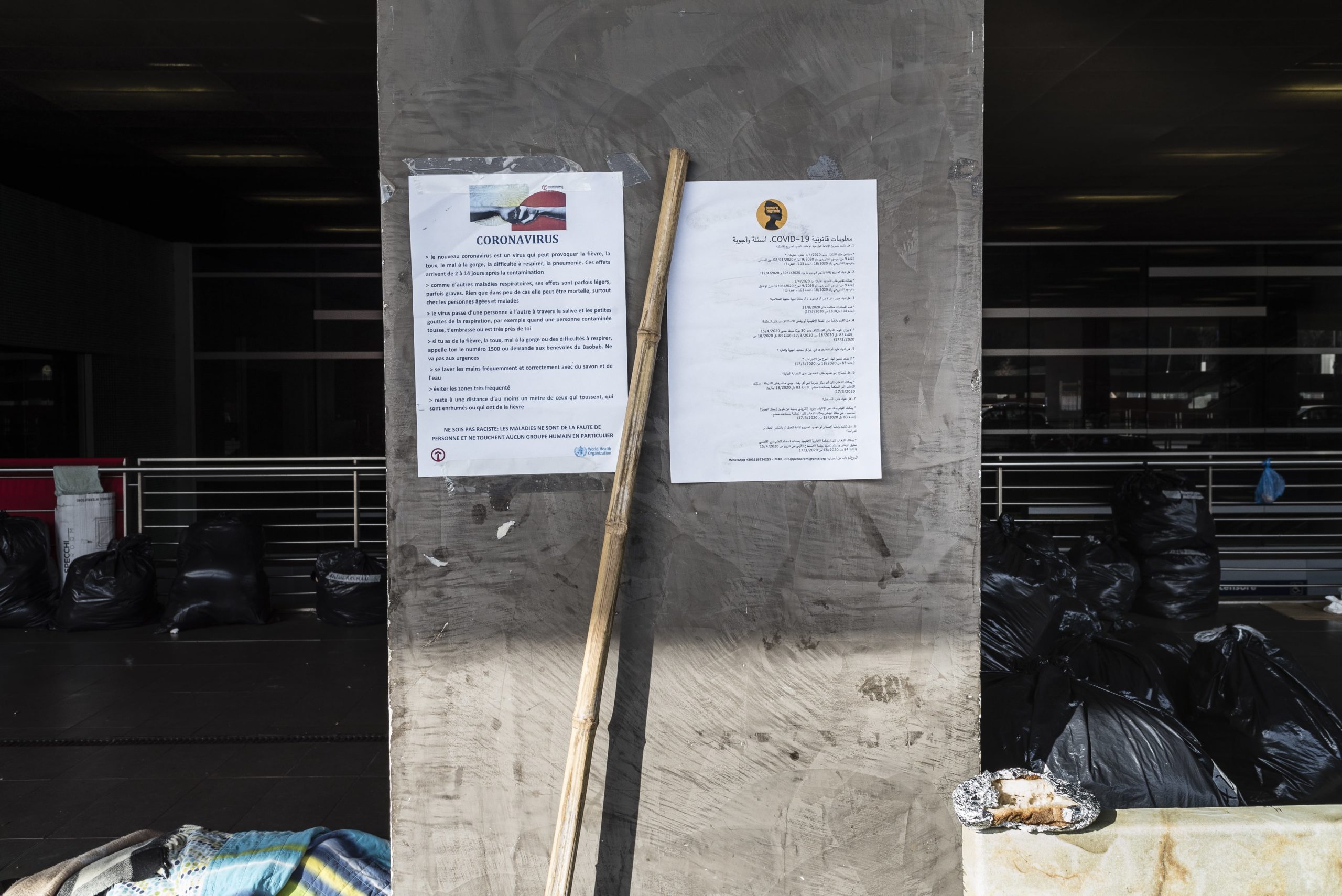

Rome, Tiburtina railway station. Some signs hung by volunteers of Baobab Experience explain the precautionary measures against the spreading of coronavirus in different languages. Around 100 migrants sleep here on the sidewalk every night. In the morning, everyone puts their blankets in a bag.

The legal status of the approximately one hundred people, mostly from Africa, sleeping here could not be more varied: some arrived a few weeks ago, some are appealing to obtain asylum, and some other, like Makan, have lost their job even though they have a residence permit.

“At the beginning it was mostly people in transit or Dubliners, then things changed,” says Andrea Costa, coordinator of the Baobab Experience volunteer association, referring to migrants arrived in Italy by sea hoping to reach different European countries, and people sent back to Italy by other member states by the Dublin Treaty, because it is where they applied for asylum. “It has been the same people for several weeks now: between closed borders and quarantine, they are stuck here.”

Just like every morning at 8 a.m., volunteers from Baobab have brought breakfast. They are equipped with gloves and masks. They hung signs illustrating risks, the need for social distancing and the importance of washing your hands, recommendations that are basically impossible to follow in this environment.

“Yesterday [March 26] – Costa says – the municipality announced they activated a phone number to report gatherings: we have been self-reporting for three weeks now and no-one has found a solution yet.”

Meanwhile, the work for volunteers has become more complicated: “Not only moving around is more difficult for some of us, but the preparation and distribution of meals has also become more expensive and complex. For example, before we would come here with a table and a big pot of pasta: we cannot do it anymore. To avoid gatherings, we prepare portions beforehand and distribute them one by one,” Costa explains.

During quarantine, access to services for migrants and homeless people, while still being assured, is generally more difficult: “Before I would go take a shower and charge my phone at the Astalli centre – Makan says – but now it is closed: they just distribute food. I prefer not to move too much anyway, I do not want trouble with the police. How can I explain I sleep on the street? And on top of that, I do not have residence now.”

#IWOULDLIKETOSTAYHOME

Homeless people are at least 8 thousand in Rome, 50 thousand in all Italy.

“When the hashtag #stayhome was launched, the first thing we thought was #Iwouldliketostayhome” says Alessandro Radicchi, founder of Binario 95, a centre for homeless people at the Termini railway station in Rome.

Here as well, the job of helpers and volunteers was not made easier by the Covid19 emergency, from the need of masks and gloves to managing spaces for meals or laboratories.

“The problem – Radicchi explains – is that there is no place for homeless people to quarantine at.” At Binario 95 they set up an isolated room in what was once an office, in case someone starts showing flu symptoms. The alternative would be to call an ambulance or to risk having the whole centre quarantined.

Radicchi is also the director of the Italian National Observatory on Solidarity in railway stations. He explains that the presence of migrants among the homeless has been increasing significantly: “We see it in every station: about 75% are migrants, and this percentage has been growing since Salvini’s decrees came into force.”

Expelled from reception centres and after the dismantling of the SPRAR network, these people were only partially absorbed by the city support network for the homeless. “But available places for migrants transiting in Rome are less than 300: thousands ended up on the streets,” Radicchi says.

ASYLUM SEEKERS WITHOUT RESIDENCE

Complicated bureaucracy adds up to social and economic troubles: as an effect of the first Security Decree, several municipalities around Italy have started denying civil registration to asylum seekers since the end of 2018.

Rome, San Lorenzo neighbourhood. With bars and restaurants closed and the whole country on lockdown, since March 9 this neighbourhood has been empty after 7 p.m.

Article 13 of the 840/2018 government bill (which converted Salvini’s decree into law) states that the residence permit for international protection reasons “is not sufficient title for civil registration.”

“The article is badly written: it actually does not forbid civil registration for asylum seekers, even though that might have been the intention,” says Antonio Mumolo, president of Avvocato di strada (street lawyer), an association that he defines as “the biggest law firm in Italy, but also the one with the lowest income, basically zero,” because they have been offering free legal advice to homeless people since 2001.

“We appealed against rejections by 50 majors and we won, obtaining asylum seekers to be registered in the Civil Registry: Italian law states that residence is a right for all citizens and all foreigners with regular permits,” Mumolo explains.

In addition to being a right, residence stems from a need for public order. “An aspect that maybe the former Minister did not take into account,” Mumolo underlines. “Civil registration answers the need to know where people are: not allowing it is a mistake on the security side.” That is the reason why several towns created a fake address to register even homeless people: in Rome, for example, that is via Modesta Valenti.

In March, the Constitutional Court should have disclosed its final decision on this matter, but in light of the Covid emergency, the proceedings are now suspended. “The problem – Mumolo concludes – is that despite court deliberations and despite such matters are under the responsibility of the Ministry of the Interior, and not the majors, different towns keep doing extremely different things.” Some, as Mumolo tells us, require not only a regular lease but also an employment contract. In a case followed by lawyer Ludovica Di Paolo Antonio, a volunteer for Baobab Experience, the municipality of Rome refused to register an asylum seeker to the Civil Registry, despite a court verdict: “Everything is on hold at the moment, all offices are closed, but we are considering filing a complaint – Di Paolo Antonio says. We do not understand why they are being so stubborn in not accepting court rulings.”

Civil registration is not only a formal issue. Residence goes hand in hand with fundamental rights: without it, you cannot obtain a job contract, open a bank account or get a VAT number; you lose welfare rights, the right to vote or to have a GP. With the Coronavirus emergency, that means your only option if you get sick is to call an ambulance. “Without residence, you’re a second-class citizen. And you cannot leave the streets” Mumolo sums up.

“CLOSE BIG CENTRES”

The recent law decree Cura Italia, one of the many measures taken to face the Coronavirus pandemic, extended the validity of residence permits until June 15. “Immigration offices are closed and proceedings are on hold, except applications for protection and expulsions – says Nazarena Zorzella, lawyer at ASGI, the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration – and this is unreasonable, considering that expulsions cannot be executed with the borders closed. All those people will crowd our CPRs (return detention centres), where it has already become impossible to maintain minimal measures to contain the spread of the disease.”

In a document issued by ASGI and Action Aid, signed by around ten associations operating in the field, the problem is clearly laid out: “If it is true that the virus makes no distinctions, it is also true that the legal, housing, work and even existential situation of many foreign citizens determines specific and unique risks, which call for an urgent discussion that also keeps public health in mind.”

With the two Security Decrees, followed by the dismantling of the SPRAR system, asylum seekers and refugees have no longer access to accommodation in small flats, and they gather in big centres with hundreds of beds: “We are asking to reorganise diffuse housing as it was before those decrees, and to allow access to such accommodation to people with humanitarian protection, who were excluded by those decrees,” Zorzella explains. A petition not only to protect migrants, but also public health and those working in the centres, as according to ASGI, these structures are not well positioned to ensure the necessary assistance and health monitoring.

And then there are seasonal workers who, in Zorzella’s opinion, “should be hosted in suitable structures to protect their health.” “Much has been said about the risks posed by elderly care homes in the spreading of the virus – Zorzella concludes –, it is equally clear that we need to pay attention to big centres hosting migrants: we are talking about 80 thousand people. We need urgent measures.”

Cover photo: Rome, Tiburtina railway station. Some signs hung by volunteers from Baobab Experience explain precautionary measures against the spreading of coronavirus in different languages. (All photos by Daniela Sala)