«I don’t think there’s anything wrong or offensive with the term “extracomunitario”. They have difficulties getting in, whereas foreign European citizens don’t. I think it is wrong to be obsessing over the terminology.»

Sociologist Enrico Pugliese is a prominent scholar of immigration to Italy. For decades, he has been tracking and mapping the immigration routes to our country followed by those seek safety and employment: a future. We showed him the Open Migration dashboard that follows the trends and changes in the migratory flows, and he told us how immigration to Italy has changed over the last half-century: from the early arrivals in the nineteen-sixties to the refugees in Lampedusa in recent years.

Can you immigrate to Italy today?

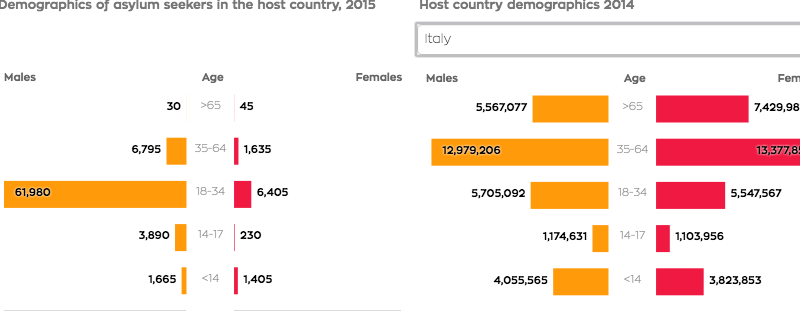

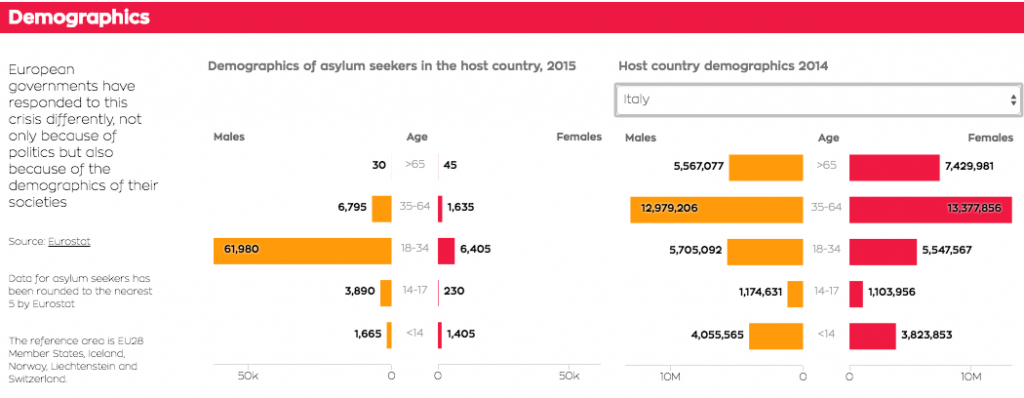

A preliminary distinction needs to be made. Those migrating to Italy from new EU member states can travel in and out without problems. This has an effect on the measured inflow of immigrants. A Romanian can come and go, he can go back to his country because he has something to do there and then return to Italy. On the contrary, those arriving from non-EU states have a much harder time. The stricter the regulations, the more stabilized the migration becomes. This also affects the data that are available to us. Currently, we have a situation where it is very difficult to get registered after arrival.

What has changed then?

Everybody has always criticized immigration amnesty programmes – you can even find some immigrants who are against it – but in fact, they have been a blessing. Italy has never been able – actually, it has always refused to find ways to facilitate regular immigration. It was discussed only at the time of the second Prodi cabinet, and never again since.

Many people who arrive in Italy are just passing through. Have we become an unattractive destination for today’s migrants?

I wouldn’t put it like that. Some want to go where their relatives are, others where there are more jobs, others where the immigration laws are more advanced and more effectively enforced. That’s all.

What should be done to regulate the arrival of migrants in Italy?

Italy, for one, has always refused to consider the introduction of a job seeker’s visa, or a system for regularizing immigrants after their arrival, like Germany did with us when we emigrated there 50 or 60 years ago. A system that I went through myself when I travelled there as a student and then changed my status after I started working. It is a step that Italy should take to simplify the bureaucratic process that plagues immigrants.

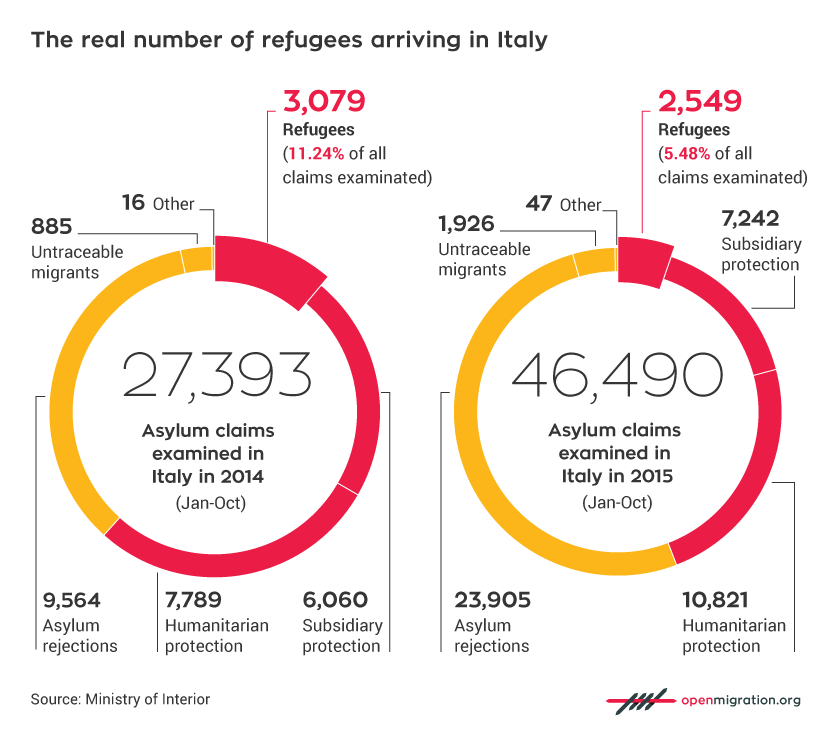

There has been a spike in the number of asylum requests in recent years. Has it become another legal channel to arrive in Italy for those who do not have the right to a visa?

It would be like saying that it’s just a trick. And whenever the immigrants do something that they shouldn’t, there is the risk of generalizing and creating a new negative label, a new stigma. Take another term that is used in a derogatory manner: “welfare shopping”. As if to say: foreigners go to certain countries so that they can exploit their social benefits. This is just another way to blame immigrants. Therefore, I would say that there may be some who apply for asylum so that they can emigrate, but we need to realize that it is very hard to distinguish between the economic migrants and the refugees.

Politicians in Italy – and elsewhere – keep emphasizing the distinctions between economic migrants and refugees. What are your thoughts on that?

It’s true; you often hear it, even from renowned politicians: refugees should be welcome and economic migrants should be repatriated. But what does that mean, other than sending them back to the hell from which they sought to escape?

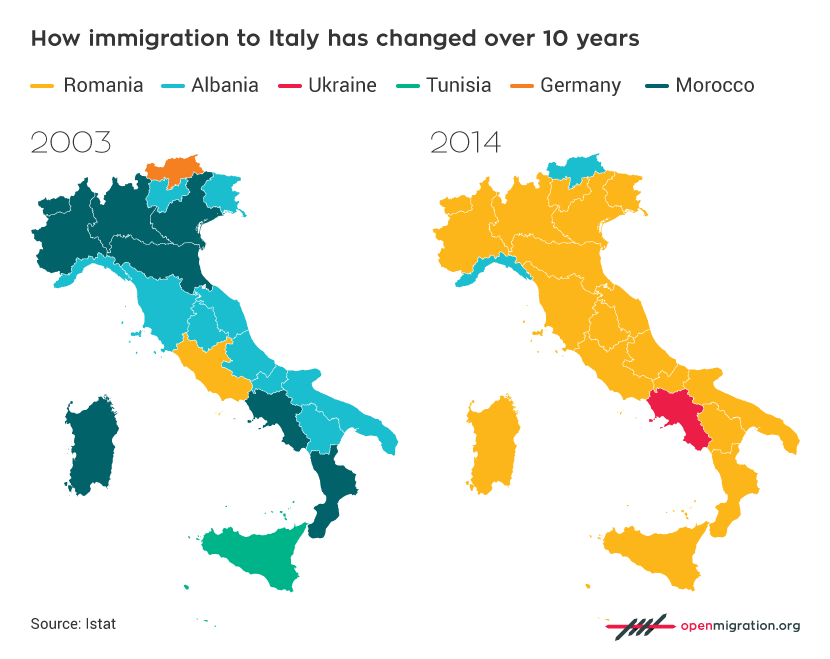

Let’s move on to the history of immigration in Italy. How has the national makeup of immigrants changed?

The history of migrations to Italy began more than forty years ago. First, the Tunisians came to Apulia, followed by women from Catholic countries of Africa and South America, working as waitresses. Then there is the unique case of the Yugoslavians who helped with the reconstruction work in Friuli after the earthquake, in 1976. Overall, immigrants were well distributed even in Southern Italy, especially those employed in housework.

There was a change in the early nineteen-eighties, as the Italians became richer.

Yes, it was the time that saw the rise of professions like domestic helpers and street vendors – the so-called “vu’ cumpra’”. Throughout the eighties, women came from South America, the Philippines and generally from Catholic countries and the Horn of Africa, while street vendors came from Senegal and Morocco. Tunisians found a home in Sicily, as fishermen, farm hands and construction workers.

What happened in the nineteen-nineties?

Since 1992, we have had reliable data on the number of immigrants in Italy. Before that, we only had numbers from the police, and they tended to overestimate the presence of Europeans. Everything changed with the fall of the Berlin Wall, obviously. The landscape changed in the early nineties. The first Albanians arrive, and then the first immigrants from the Eastern Bloc, few and far between. Then, from the late nineties onwards, the immigration became more Christianized and de-Islamized. We saw the first arrivals from Romania, reaching their peak in the early Noughties, when the country joined the European Union.

How has female immigration to Italy changed?

There is a relationship between the demand and the cultural traditions, what is called job sex segregation – that is, the segregation based on gender, nationality and the cultural traditions that are attached to it. For instance, with a few exceptions in Sicily, only rarely do we find Islamic women employed in housework. They are mostly Christian, who worked as waitresses in the nineteen-seventies and today they are mostly employed in care work.

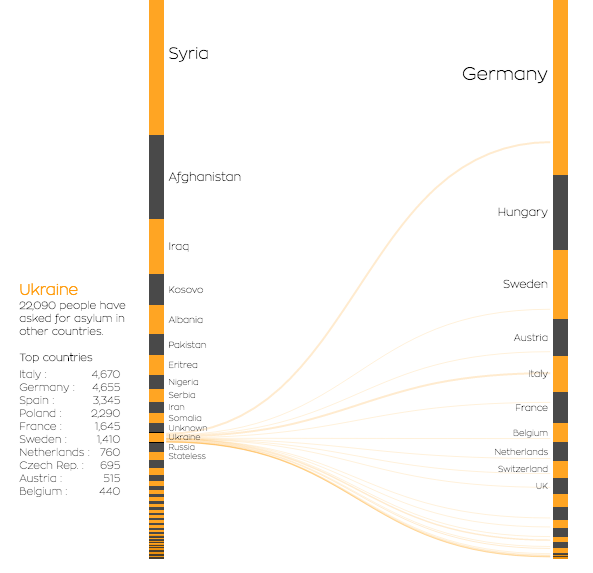

Then there is the case of Ukrainian women, which we discussed on Open Migration.

Women are arriving from certain countries, including Ukraine, because there is an unfulfilled demand for jobs. There is a misguided notion that immigrants arrive because they arrive, that they are pushing to get in. Actually, they are pushing to get in because there is an unfulfilled demand for jobs in Italy. So, when there is a demand for caretakers, the response was women, willing to travel alone, and that’s how the influx of immigrants from the Ukraine originated.

What type of immigration is taking place from the Ukraine?

Ukrainians are a mono-occupational nationality, with a certain amount of social mobility. The daughters of Ukrainians go to school and to university. And we cannot help noticing how this is an effect of mass schooling in the USSR and the process of female emancipation in the Eastern Bloc. These things always happen at a molecular level, yet they are representative of a trend in the national communities. The same applies, in part, to Romania and Albania.

(Translation by Francesco Graziosi)