A trial for a tragedy with no culprits. There are still too many unanswered questions, the first of which being how many people are missing. The recurrent figure seems to be 268 (60 of whom are children), but the only reliable numbers concern the 212 who were rescued and the 26 bodies retrieved from the sea. The passenger who called the harbourmaster’s office, Mohammed Jammo, can only estimate the presence of 300 to 400 people on that fishing boat which left Zuwara headed for Lampedusa on October 10, 2013. A Maltese plane flying over the area communicated to Malta’s Rescue coordination centre (RCC) that there were about 250 people on board. In addition to having no culprits, the tragedy lacks victims. If the trial has begun to establish the truth, credit must go to Mohammad Jammo, the man who first reported this story to the police together with two doctors on board with him, Mazen Dahhan and Ayman Mostafa. All three of them lost their children in the shipwreck.

An account of the facts – as complete as possible

October 11, the day of the shipwreck, 12:26 a.m. Mohammed Jammo, a Syrian doctor escaped from Aleppo, calls the Italian maritime rescue coordination centre (IMRCC), headquartered in the harbourmaster’s office in Rome, for the first time: “We are taking in water, we are in danger, help us.” As he tries to explain on the phone, during the night they had been shot at by two Libyan boats. The entire conversation between Jammo and the Coast Guard can be heard in a documentary by Fabrizio Gatti entitled “Un unico destino” (“One Single Fate”). The officer plays for time and tells him to call Malta. The phone calls become ever more frequent: 12:27, 12:39, 12:40. In hindsight, it is clear that the Syrian doctor’s insistence was due to a dramatically tangible danger. All he gets are evasive answers, sometimes even incorrect ones: “You are closer to Malta.” This is untrue and Jammo knows it: the Maltese had told him so when he called them upon receiving their number. For this reason, he turns to Italy for one last time at 1:17 p.m. “Please come, we are dying,” he implores.

An excerpt from the case file

Even after that last call, in Rome they continue to hold to their position: “You’ve got to call Malta.” The island has officially been in charge of the rescue operations for the last 17 minutes, and at 2:35 p.m. the IMRCC receives a fax confirming the fact that Malta is indeed coordinating the mission. In fact, even though the migrant boat is 61 miles away from Italy and 116 from Malta, the Search and Rescue area (SAR) – the international waters where rescue missions are held – falls under Malta’s jurisdiction. As we have already discussed, the island has unilaterally decided to take charge of far too big a SAR zone for their capabilities. As a result, Italy always has to compensate when they come up short, as the defendants state when questioned. Furthermore, Malta sends another maritime patroller to the coordinates given by

Dr Jammo: their management of operations is unquestionable.

Between 1 :00 and 1:57 p.m. the Italian harbourmaster’s office sends a warning to all ships in the area and to the Command in Chief of the Italian Fleet (CINCNAV), the operative department of the Naval staff, whose task it is to control vessels at sea and planes on aircraft carriers. At 1:34 a subordinate asks Luca Licciardi, the highest ranking officer, whether the Libra patrol boat should be sent on site. He replies: “Not yet.” The military vessel is 27 miles away from the migrant boat. With a cruising speed of 20 knots, it could reach them in an hour and a half. And yet, despite Jammo’s messages, at the CINCNAV and IMRCC coordination centres, according to the officers involved in the operation, no immediate danger is foreseen.

At 2:50 p.m. the harbourmaster’s office in Rome sends Malta a fax indicating the three ships that are closest to the position of the endangered boat: the Libra and two merchant vessels. At 3:12 p.m. Malta communicates that it is sending a Maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) flown by George Abela, a retired Maltese air force captain. Twenty minutes later, the Navy command suggests that the Libra stay about one hour away from the migrant vessel’s position; consequently, the ship, which was carrying out a military patrol mission, moves within a 17 to 19-mile radius. In that area, a so called “fishing war” has been going on for years: there, Italian fishing boats are often attacked and even seized by Tunisian or Libyan vessels. This information is transmitted to Malta, too. As the GIP states, the IMRCC communicated to Malta’s MRCC that “the Libra played an important role in identifying new targets” (meaning that it would be better not to move it), but that “if moving the navy ship was the only solution, they could use it.” The highest ranking officer at that moment is Leopoldo Manna, chief of the third office of the harbourmaster’s coordination centre.

At 5:04 p.m. Malta sends a fax to the IMRCC: the Libra must move and check the situation of the damaged fishing boat. Leopoldo Manna forwards the order to Luca Licciardi at the CINCNAV. Just three minutes later the migrant boat overturns. The Libra, already heading towards it, is informed of the tragedy within the next seven minutes. It reaches the site at about 6:00 p.m. and half an hour later Malta appoints it as the ship in charge of operations.

Points in favour of and against the defendants

When the public prosecutor asked the case to be dismissed there were seven defendants, officers, and petty officers of the Navy and the Coast Guard. Now there are only three: charges against the others have been dismissed. These last few include the highest ranking officer, Admiral Filippo Maria Foffi, a 64-year-old who was the commander in chief of the Navy squadron. Now retired, he was formerly the head of Mare Nostrum, the humanitarian operation of the Italian Navy that made rescuing over one hundred thousand people possible. Foffi fought to defend Mare Nostrum, but in this trial, just like the others, he has been charged with failure to offer aid and with negligent homicide. The dismissed charges concern two officers of the Coast Guard (Clarissa Torturo and Antonio Miniero), and subordinates like frigate captain Nicola Giannotta of the CINCNAV who simply transmitted the orders to the Libra.

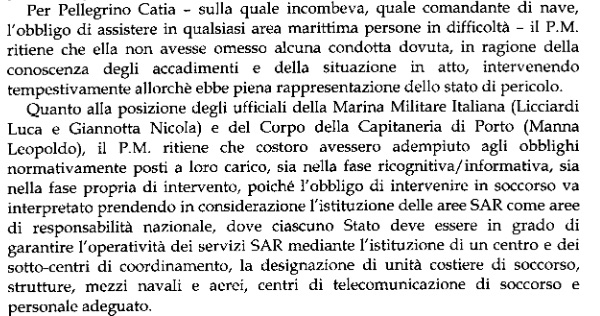

Pending charges involve Catia Pellegrino, the Libra’s commander; Luca Licciardi, chief of the CINCNAV; and Leopoldo Manna, chief of the third office of IMRCC. Their defence insists that the operation should have been conducted by Malta’s RCC and not by Italy and furthermore, according to the GIP who reported their position, the obligation to intervene only applied after the migrant vessel had overturned. And thus, harbourmaster and Navy officers were not responsible for the accident. The GIP defined these positions as “hardly convincing.” If on the one hand he does acknowledge their strict compliance with international protocols and sea rescue conventions until 4:22 p.m., after that time, he underlines that the two orders “were not issued in a timely manner”: making the Libra ship available for rescue missions and proceeding autonomously to avoid any danger for the migrants’ lives. This is the key point to understanding why the case against Pellegrino, Manna, and Licciardi has not been dismissed. The prosecutor now has 30 days to issue a new charge against the latter two: such a decision is called “compulsory incrimination”.

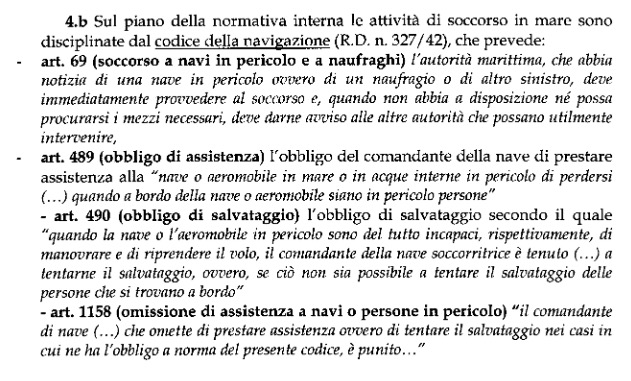

An excerpt from the case file

Regarding Catia Pellegrino, commander of the Libra P402 patrol boat, the GIP has asked for further investigations. The charge of failure to offer aid is paradoxical for the woman who represented the Italian Navy during Mare Nostrum when the Libra was involved in humanitarian missions whose only purpose was to rescue migrants at sea. Mare Nostrum was announced by Prime Minister Enrico Letta right after the accident of October 11 and lasted about one year. State-owned RAI television celebrated this mission in the documentary film “La scelta di Catia”, which saw Commander Pellegrino as the protagonist.

According to the statement of the Syrian doctors’ lawyers, the Maltese aircraft overflying the shipwreck area “sent many warnings on the emergency channel 16, without obtaining any answer from the Libra.” However, such warnings could also have been received by the other ships listening to channel 16 that are not mentioned in the GIP’s decree. Precisely for this reason, the judge requires further inquiries. Fabrizio Gatti, a journalist for the Italian magazine L’Espresso, talks about this episode in an article relating the content of a secret report by Malta’s armed forces, where the attempts of the aircraft to contact the Libra are detailed. Arturo Salerni, lawyer of the three survivors together with Alessandra Ballerini and Emiliano Benzi, highlights that, from their point of view, there is a huge gap in the investigation, as no letters rogatory have been issued to Malta. Therefore we still do not know whether the messages were actually delivered to the Libra.

In its judicial decree, GIP Giorgianni defines the position of the CINCNAV officers as “strongly critical”. Considering their military position, responsibility falls on the higher ranking officer, Commander Luca Licciardi. He was the one who ordered the Libra, through Frigate Captain Giannotta, to “stay out of the way when the [Maltese] patrol boats arrive.” Experience had taught Licciardi that the Maltese ships would do a U-turn if they saw them.

For this reason he added: “Call them up [the Libra patroller] on the phone. Oh, the patrol boats are coming, don’t let them find you on their way or they’ll go back.” This is how Licciardi, as the decree reads, “imposes the Libra ship to leave the predictable course of the Maltese rescue vessel and avoid revealing its position to the authorities that were coordinating the rescue operation at that moment.” And then there’s the “not yet” he gave to his subordinate at 1:34 p.m.: the judge considers his explanation “not completely convincing” as the two merchant ships that should have been closer to the migrants were soon diverted towards Malta or were too far to intervene.

Malta, the unwelcome guest

The trial promises to be very long. The dismissal of charges against Admiral Foffi could mean that charges will also be dropped against the whole Navy, and this is positive. But personal responsibilities remain, as well as huge gaps in reconstructing the way Malta coordinated the operation. For once Malta did not avoid its duties, and it resulted in tragedy. And according to the Syrian lawyers, it is all due to Italy’s failure to properly follow orders.

For the defence lawyers, however, the reason is to be found elsewhere. For example, how the plane piloted by George Abela conducted its patrolling operations above the accident area. As the GIP reports, Catia Pellegrino gave her hypothesis about the reasons for the boat overturning when questioned: the migrants waved their arms when they saw the plane, and that movement tilted and unbalanced the vessel. The images and words of the Maltese RCC officers demonstrate that the fishing boat overturned, but did not sink. Once again, the lawyers have opposing views on this matter. The Syrian ones maintain that the Italian Navy could have intervened in advance and in compliance with international conventions, thus avoiding any risks for the people on board. In fact, the seriousness of the situation was obvious. According to the officers’ lawyers, instead, the role of the Maltese plane exonerates Italy completely; had it been more careful, this tragedy would not have happened.

In particular, there is a gap in the chronology which is acquiring greater importance and could determine the future judicial story. What happened between 4:22 p.m., the last time indicated by the GIP when the IMRCC and the Italian Navy were strictly following the international protocols, and 5:07 p.m., when the boat sank? During those 45 minutes, while the Italian officers were playing for time and to some extent failed in their duties (according to the GIP), what did the Maltese do? Any answer given to these questions will not bring the victims back. But trials are held based on criminal allegations and liabilities: delaying intervention is not necessarily equal to causing someone’s death. And the reason the boat overturned is certainly among the causes of the shipwreck. Was it just the water coming through the holes left on the hull by the Libyan bullets, or was there something else? This is not irrelevant. Based on the conclusion of the current GIP, which could or could not be approved by the judge of the trial, the turning point remains within those fateful 45 minutes.

The tangible risk is that the outcome will be as predictable as it is unsatisfying: the culprit of this tragedy is bureaucracy, Italian and Maltese authorities passing the buck to one another while, nevertheless, abiding by the laws. A “disaster of bureaucracy”.

Translation by Lucrezia De Carolis. Proofreading by Alex Booth.

Cover photo: Stefanie Eisenschenk, 2015 (CC BY 2.0).