It is a Sunday evening in early September, and the feeble lights of the “fadas”, shops and meeting points for young people, dot the uneven streets in the northern neighbourhoods of Agadez. Scattered voices echo in the dark, interrupted by the noise of the yellow tuk-tuks, the main public transport vehicles of this city in the heart of Niger. Joseph Moussa, who everyone knows as Idris, is sitting on a mat in the street outside a cousin’s house. Sheltered by the darkness and cooled by a gentle breeze, he recalls memories so far away, and at the same time so close, of a region where borders do not exist, apart from those imperceptible and fragile ones between communities, families, and trades.

The pass of Tumu

Moussa – 43, a thin man – has the quiet yet watchful attitude of many soldiers from the Sahara, accustomed to an unfriendly climate and endless waits. For more than four years he has guarded the pass of Tumu, the main border checkpoint between Niger and Libya, a place that is becoming increasingly familiar to European chancelleries as the key to controlling migration flows. Now, however, Moussa is back in the city of his birth, Agadez. Phone in hand, he keeps scrolling through the pictures of patrols in southern Libya and of his four children, who live with his wife in Murzuk, second city of the Libyan Fezzan, 1,500 kilometres to the north.

“Have you ever heard about the seizure of Al Gatrun? I was there, I was one of the 14,” Moussa says, prodded by a friend. The deed he is referring to, dating back to June 2011, has spread from mouth to mouth and reached epic proportions among young Toubous, lords of the central Sahara tracks together with the Tuaregs. “When the protests erupted, the old Barka told us we had to overthrow Gaddafi because he was an enemy of Libya and the Toubous, so I followed him.” Together with a handful of men, Moussa participated in liberating the town of Al Gatrun and of the two main centres of southern Libya, Murzuk and Sebha, from the Colonel’s troops.

He is one of the most fervent followers of Barka Wardougou, a warlord and long-standing leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of the Sahara (FARS), a Toubou militant group that participated in the rebellion in northern Niger in the 1990s. “Thanks to Barka we gave life to the southern revolution, we freed city after city with our own hands,” Moussa proudly points out, remembering the birth of the Katiba Dra Sahara, the Sahara Shield Brigade, which later merged with the Military Council of Murzuk. In 2013, when the Fezzan region had already become the battleground for dozens of armed groups engaged in a seemingly ceaseless and dirty war, Barka asked him to “guard the pass of Tumu, on the border between Libya and Niger, with a few more men.”

The border controlled by militias

Until the summer of 2017, Moussa’s days were marked by the passage of vehicles laden with goods and, above all, people he forced to pay a tax to enter and leave Libya. Too few patrols for such a vast area; his men were only able to control less than one fifth of the 350-kilometre border between Niger and Libya. In 2015 they helped the French – who had just installed a military base in Madama, in the north of Niger – during an operation along the Libyan border, between Tumu and the pass of Salvador, 200 kilometres to the west. An area widely known for drug, alcohol, and cigarette smuggling.

“As soon as we settled in Tumu, the Libyan transitional government gave us 15 pickups, and then forgot us. And yet we’ve stayed, even without a salary, living on the taxes we get from the migrants. Tripoli should thank us, as we have impounded and burned loads of Tramadol and limited the arrival of jihadist militants.” Moussa feels Libyan, maybe more than Nigerien, even though he only obtained official citizenship in 2008, after 16 years of work in Libya “where I arrived with Europe in mind,” because Gaddafi denied that status to most Toubous.

Disillusioned by the lack of support, worried about the internal factions in the Toubou tribe, and facing poverty because of the reduction in migrants crossing the Tumu checkpoint, he moved to Agadez, far from the tensions of Fezzan. “The number of migrants has been constantly decreasing over the last year, but the real change is more recent. Since July 2017, migrant vehicles heading for Libya every day have gone from 20-30 to the current five, ten at the most.”

A drop that is probably due to the increase in Nigerien personnel working at the military base in Madama, the very last border post, 100 kilometres south of Tumu. From 200 soldiers to the present 450, plus about 200 French servicemen. Only the last step in the progressive strengthening of anti-immigration checks carried out by Niger’s security forces around Agadez and between Dirkou, Séguédine, and Dao Timmi, towards the Libyan border, since September 2016.

But did arrivals in Libya really drop?

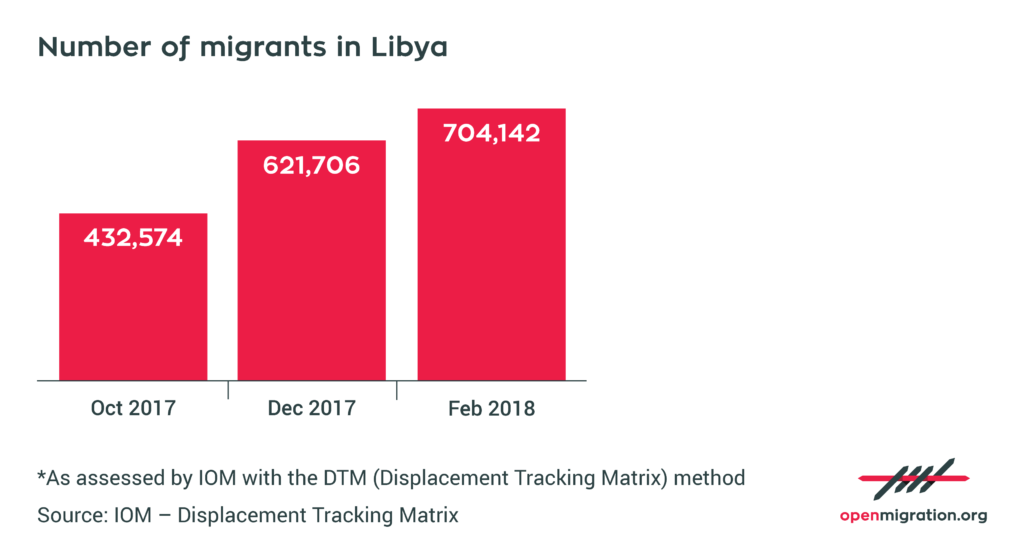

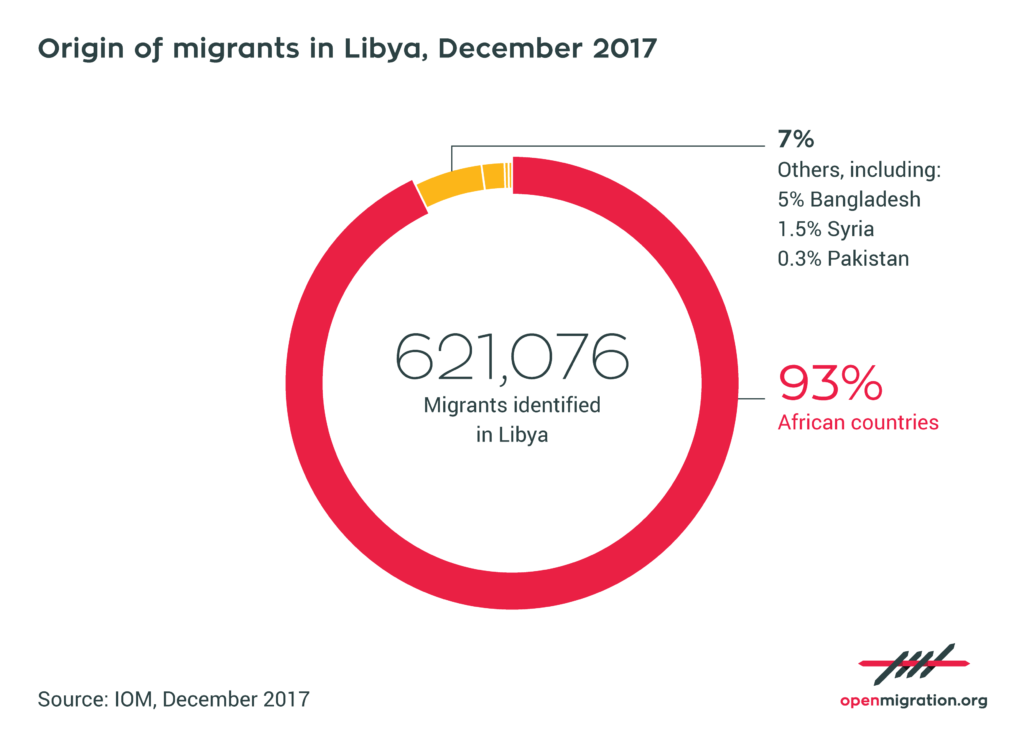

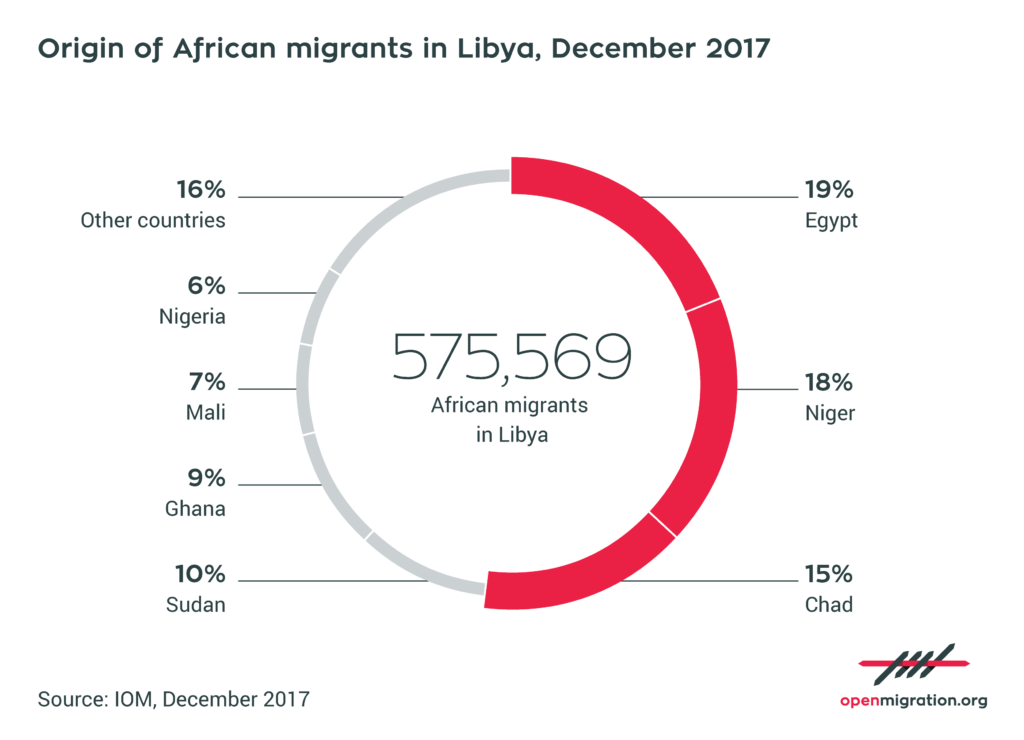

Nevertheless, migrants keep entering Libya. In fact, the data mentioned by former Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Angelino Alfano, claiming that “migrant arrivals in Libya have fallen from 290,000 to 35,000” thanks to “Italy’s political intervention” at the beginning of February 2018, only tell half the story. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), the source of Alfano’s statistics, actually outlines a completely different story: if it is true that crossings towards the north registered at the checkpoint of Séguédine, an oasis along the main route between Agadez and Tumu, dropped from 290,000 in 2016 to 33,000 in 2017, it is also true that within a month, from the end of December 2017 to the end of January 2018, the number of migrants arriving in Libya and counted by the Displacement Tracking Matrix database rose from 621,000 to 704,000. This confirms a peak at the beginning of the new year, and the constantly growing trend that started in the spring of 2017. January was also the month during which IOM recorded peaks of 536 entries a day – the equivalent to 20 Toyota pickups of passengers – in the oasis town of Murzuk, 300 kilometres north of Tumu, on the road towards Sebha and the north. This proves the existence of alternative paths or old tracks that are not monitored.

In short, migration routes are far from being closed, and the fact that they do not cross Tumu anymore does not mean they do not reach Libya. According to an internal document of the European delegation we have seen, “both IOM and Eucap Sahel Niger [EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy mission] confirmed, more than once, the emergence of unforeseeable and ever-increasing new routes,” so much so that the number of migrants who have arrived in Italy by sea, registered and disclosed by the Italian Interior Minister, seems to be the only reliable fact. This explains why one of the first recommendations made by Frontex, the European border agency which sent its third extra-EU liaison officer to Niger in August 2017, after ones made in Turkey and Serbia, was – as the Agency itself explained – to “interview migrants in Italian hotspots in order to monitor migration flows through Libya.”

If the increase in the number of migrants registered by IOM in Libya is partly due to the inclusion of previously uncounted nationalities (Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia), and to the fine-tuning of investigation procedures, the amount of arrivals in the oases of Murzuk and Kufra, along the entry route from Sudan, seems to undermine the claims of the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

For Frontex, which is negotiating a specific agreement with Niger, the priority is to control the 350-kilometre border between the Saharan country and Libya. A programme that saw the diplomatic intervention of Italian Interior Minister Marco Minniti, promoter of the agreement between three tribes from Fezzan – Toubou, Tuareg, and Awlad Suleiman – signed in Rome in March 2017. His purpose was to reconcile the three main communities of the Fezzan region, which have been in conflict for years, with a view to creating, in Minniti’s words, “a Libyan border guard to control the southern borders”. But the agreement immediately proved shaky when the Toubou delegate was repudiated by his fragmented and well-armed community as soon as he returned home.

The unstable reconciliation in Fezzan

According to Maria Nicoletta Gaida – founder of the Ara Pacis Initiative that contributed to the negotiations conducted by the Italian government – “reconciliation between these tribes is the first step towards a peaceful Fezzan; however, the agreement is at a standstill,” because “the conditions required by the three communities have not yet been fulfilled.”

Their first request is the reopening of the airport in the southern capital of Sebha, which “the militias handed over to the Libyan government last July. 900,000 euros would have been sufficient to restore it, but no one wanted to commit.” Furthermore, “the proposal advanced by the militias and police units of the Murzuk area to create a unified force for border control found no support,” Gaida adds. The leaders of Fezzan, she concludes “are more and more inclined to distrust the actual intentions of Italy and the European Union to stop migration.”

While we are sitting in a cafe in the Roman neighbourhood of Trastevere, Gaida continuously checks her phone. It is the beginning of February 2018 and Sebha is fighting once again, a new escalation bound to last the whole month. News gets around. Awlad Suleiman militias against Toubou militias, but also – and increasing by the day – fights among different Toubou groups,which have been infiltrated by fighters of rebellious movements from Sudan and Chad.

Fezzan is like a vortex attracting all the tensions in the area, where the fight involves, together with the governments of Tripoli and Tobruk, people expelled during other rebellions in the Sahara. Meanwhile, according to some sources, Italy and France keep interfering with each other’s plans here too. Past colonial disputes are being revived by tangible symbols: the stronghold of Sebha, dedicated to Queen Elena of Italy and conquered by France in 1943, today is the epicentre of conflict in the city.

A new militia, while migrations continue

And now an old acquaintance of Italy’s just came back into sight in this complex match to control the border: Barka Sidi, or Shidimi, former lieutenant of Barka Wardougou in the FARS, supported and then disavowed by Gaddafi, who ordered his hand and foot amputated. He was known to the Italian secret service for kidnapping two tourists from Veneto in August 2006, whom he held hostage for almost two months and released after Tripoli’s mediation.

In September 2017 Shidimi returned with a new group: Suqur al-Sahara, the Desert Hawks Brigade. Pictures and videos of men in uniforms and armed jeeps circulated quickly in Whatsapp groups used by Toubous to exchange information across an extremely vast territory. The militia declared the Libyan border closed for three months, a decision that divided the Toubou community in Agadez, where Shidimi’s family has been living for years. Though some applaud this initiative, deemed important to ensure the safety of the communities in that desert area, others regard the ex-rebel as nothing but a drug trafficker with political ambitions who might cause additional problems.

“Controlling the southern border is fundamental for the safety of Libyans,” Joseph Moussa states, whose position in Tumu was slightly south of that occupied by the Desert Hawks in their first patrols on the road to Al Gatrun. “But Shidimi will face the same problems we face: who should we hand over intercepted migrants, drivers, and traffickers to? And are we really entitled to arrest them?”

These attempts by the new militia reveal a political and juridical void. According to several sources, Shidimi’s attempts to approach the government of Niger and the European Commission have so far been unsuccessful. In October 2017 he apparently wrote them a letter asking for three million euros a year to finance a force of hundreds of men and vehicles. Relationships with the two governments in northern Libya have also been contradictory and, again, ineffective.

Strong approval might have come from the Toubou community in northern Niger. According to the vice-mayor of Dirkou, Dogo Tari, Shidimi allegedly visited the communities of Kawar, a group of oases on the main track between Agadez and Tumu, in July 2017. There he promised to enrol 500 young militants if the project of the Desert Hawks worked, and he gained a significant following, also because young Toubous, protagonists in migrant transportation from Niger to Libya, keep trying their luck on new routes. One of the most worn tracks circles the Tumu pass to the east and crosses Tajhari, the Libyan estate owned by the family of Barka Wardougou (dead in 2016) and now base camp of the Katiba Dra Sahara.

So, as controlling the eastern side of the border, with Tumu at its centre, looks impossible at the moment, the attention of the Italian government has turned west towards Algeria, which is crossed by the second most important track between Niger and Libya and cuts through the Salvador pass. A more arduous route, known for drug and arm trafficking and controlled by Tuaregs, who according to several sources are increasingly using it to transport migrants, too.

This would be the framework for the proposal launched in December 2017 by Minister Minniti and covered by the website Africa Intelligence, which foresees an Italian logistic base to be established in Ghat, a town controlled by Tuareg militias and only accessible by plane, approximately 250 kilometres from the pass of Salvador. The purpose would be the creation of a Libyan border guard. Apparently, ad hoc funding – 35 million euros according to Africa Confidential, that include other interventions – would already be available for Italy in Brussels.

The game for controlling what Marco Minniti defined “the southern border of Europe” to “be sealed” is still open. However, last year’s experience shows that focusing solely on control, while leaving aside the safety and well-being of communities living in northern Niger, especially in Fezzan, might prove counter-productive. For the people living in Fezzan, beaten by the conflict, for migrants, facing increasing risks, and – perhaps – for Europe itself in its attempt to contain migrations.

“We rebelled against Gaddafi but we have obtained nothing,” Joseph Moussa concludes, tens of cigarettes later, in an Agadez falling more silent by the minute. “Migrants are our sole currency: only when we find a new one we will stop transporting them.”

Cover photo: military patrol at the gates of Agadez (photo: Giacomo Zandonini)

Translation: Lucrezia De Carolis. Proofreading by Alex Booth