The birth of Fortress Europe and the detention camps for foreign nationals

Any discussion about migrants and asylum seekers in Italy and across the European continent should begin by taking a look at the figures: every year Europe, a reference point for the protection and safeguard of human rights and fundamental liberties, detains about 600.000 foreign nationals (about 40.000 of which are minors), on the basis of a mere administrative decision, with no crime having been committed. It must be noted that these are only estimates, because it is not possible to obtain accurate numbers, given the great difficulty of accessing the relevant data (as reported by the Access Info & Global Detention Project).

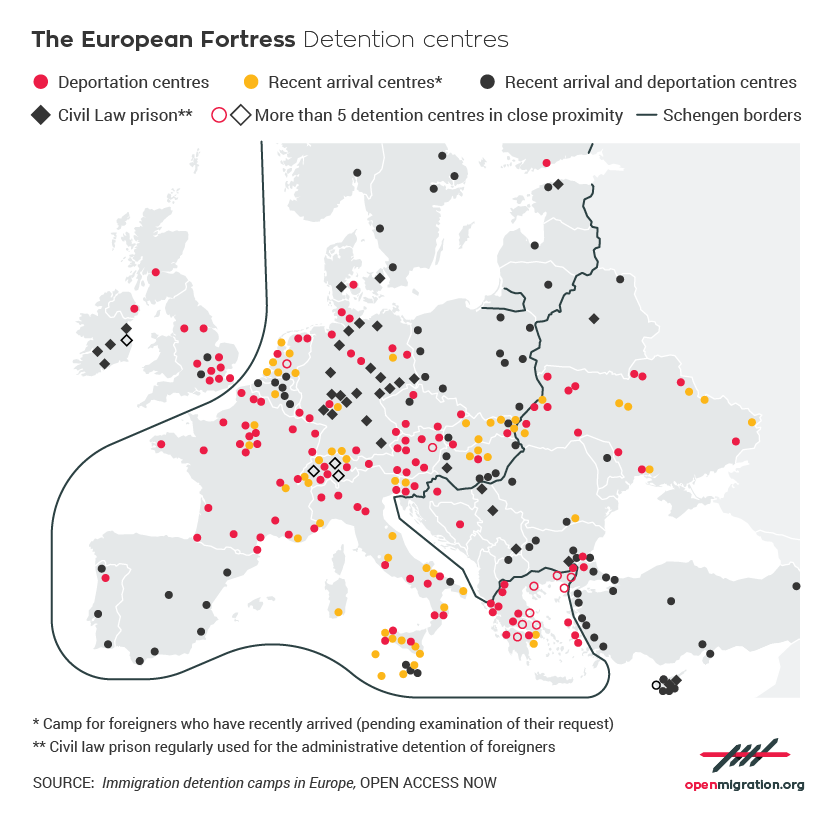

However, in order to illustrate the state of the art of administrative detention of migrants and asylum seekers in Europe, one must go back to nearly thirty years ago. It was in the nineteen-eighties and nineties, with the signing of the Schengen Agreement (1985) and the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty (1993) – and the consequent affirmation of European citizens to move freely within the Community – that the EU gradually began to look like what has recently been dubbed “Fortress Europe”. The opening of the borders within the area of free circulation for EU citizens has coincided with the closing and the fortification of the outer borders for citizens of non-EU countries. This process of strengthening of the outer borders – originated by the belief that the abolition of checkpoints along the inner borders, without proper regulation, would be a threat to public order in Schengen countries – has had the effect of legitimizing the systematic recourse by member states to the restrictions of personal liberties of the citizens of non-EU countries.

While it would be unthinkable for a German, Austrian or Italian citizen to be deprived of his or her freedom without having committed a crime or a simple administrative offense, this is the norm for non-EU citizens residing within the Schengen space (or in non-member States where the Dublin III regulation is applied, such as Switzerland). In many European countries, migrants can actually be detained in enclosed facilities pending the examination of their asylum request, or until they are forcefully repatriated to their countries of origin or relocated to another EU country, as per the Dublin III Regulation. Foreign nationals, however, are not only confined in detention centres, but also in the transit centres at border crossings in airports; these are particularly sensitive spaces, with serious violations of international regulations and the fundamental rights of the individual taking place, among which the principle of non-refoulement, which forbids States to send migrants back to countries where their life or freedom would be in danger, as per Article 33 of the 1951 Geneva Convention and the attendant 1967 Protocol, as well as Article 3 of the 1984 Convention Against Torture.

From exceptions to systems

The very few who are able to reach Europe have to contend with the red tape and the innumerable traps of the EU and national regulations.

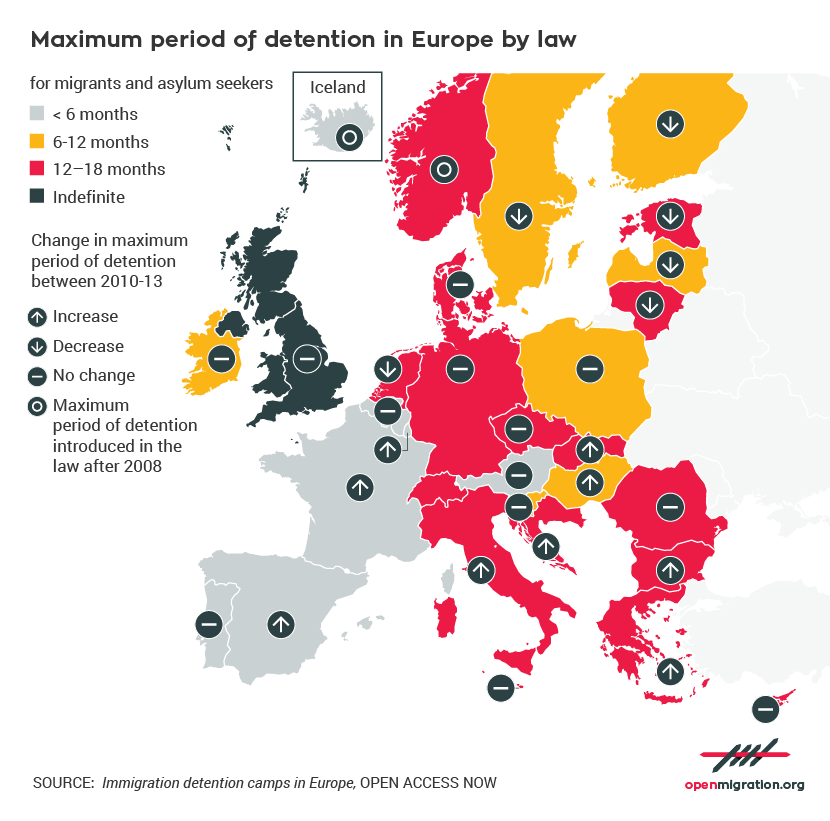

While it is a true and established, albeit controversial fact that in all EU countries, those subject to an expulsion order can be detained until repatriation, this is not the only condition leading to the deprivation of personal freedom. In most European countries, grounds for detention include entering or residing in national territory illegally (see Germany and Sweden, among others), refusal to depart voluntarily or to comply with non-custodial measures (Hungary), identification proceedings (United Kingdom) and prevention of illegal entry or expulsion (Sweden and Hungary, among others). In addition to this, many countries (among which the United Kingdom, Romania, the Netherlands and Ireland) have introduced the criminalisation of irregular migrants upon entering, re-entering and staying, all of which are punishable with fines, but also with prison. And some non-EU countries, such as Switzerland, are detaining asylum seekers pending transfer to a member State identified as responsible for examining their asylum request.

UE, 2016: a legal double standard and a double system of protection of personal liberties

Administrative detention of migrants and asylum seekers in Europe has therefore been made institutional, and has become a key point in the management of migratory flows. It is not unusual, in the United Kingdom, but also in the Netherlands, in Germany and France, to name only a few countries, that unaccompanied children and minors are detained for up to 18 months – in flagrant violation of the principles of family unity and best interests of minors (as fundamentally defined by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child), and in conditions that are often denounced by NGO as below human dignity. Detention centres for migrants seem to reverse the relation between safety and freedom, which lies at the heart of the modern regime of human rights protection, with the effect of creating a double legal standard and a double system of protection of personal liberties. In the case of EU citizens, protection of the individual rights means that restriction of personal freedom can only be applied under conditions of grave threat to order and safety, while in the case of migrants, the States’ need to control the borders to prevent unwanted intrusions tends to overshadow the protection of individual liberties.

That is to say, we are holding on to our rights and leaving others to fend for themselves, even when they are risking their lives and their freedom.

(Translation by Francesco Graziosi)