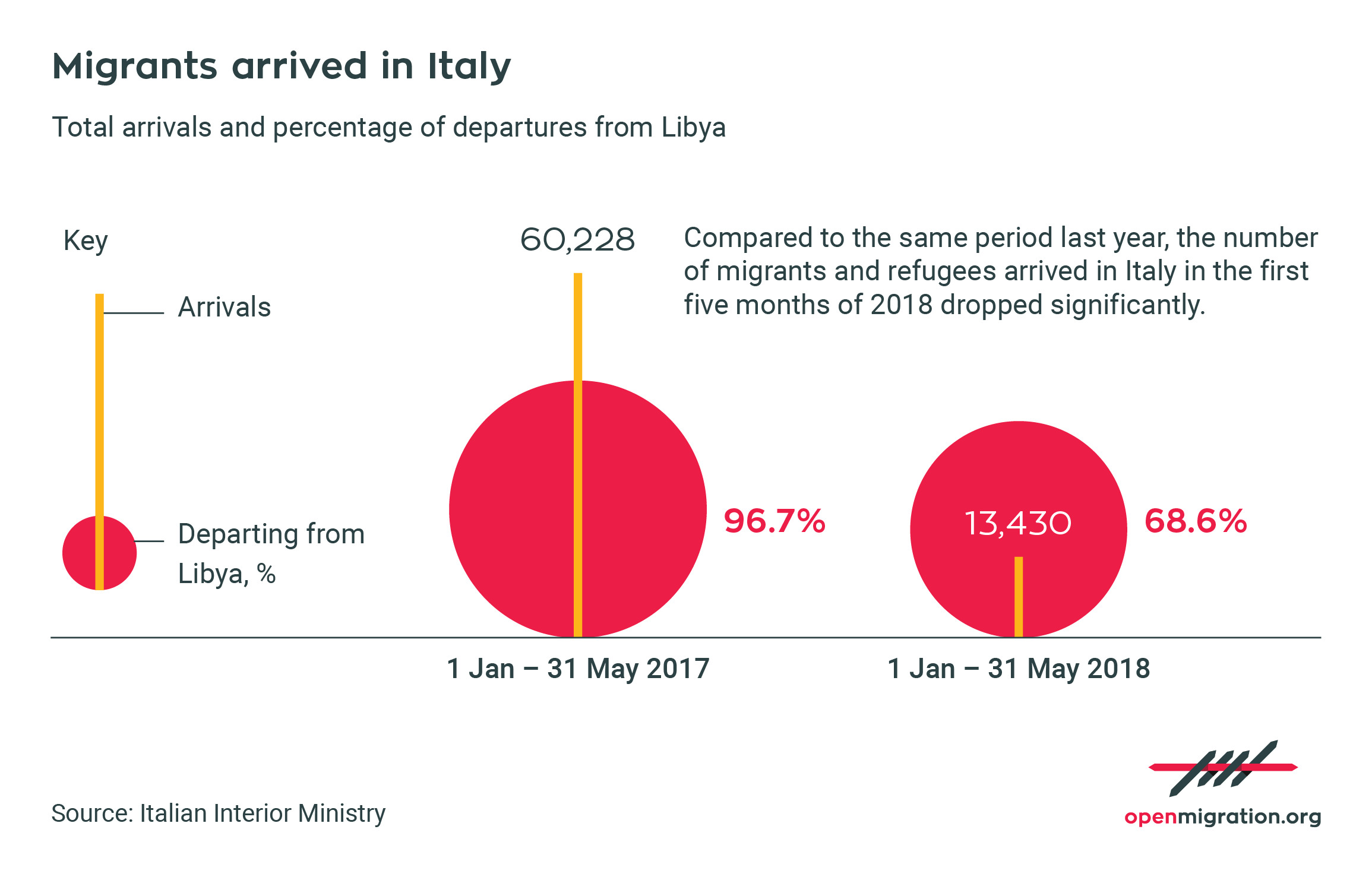

Between 1 January and 31 May 2018 13,430 migrants and refugees landed on Italian shores, according to Italian interior ministry data. This represents a 77.7 per cent drop with respect to the same period in 2017, when arrivals to Italy stood at 60,228.

Of the arrivals in the first five months of this year, 9,214, or 68.6 per cent, reportedly departed from Libya. This is an 84.2 per cent reduction over the first five months of 2017, when arrivals from Libya amounted to 58,258, or 96.7 per cent of the total, according to the same source.

The reductions are to be seen in the context of the Memorandum of understanding spearheaded by Italy’s then Interior Minister Marco Minniti and signed in February 2017 by Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni and the head of the Libyan government of national accord Fayez al-Serraj in order to stem the flow of illegal migrants through Libya into Italy.

Since then, under the terms of the agreement Italy has strengthened the technical, technological and material capacity of the Libyan coast guard to intercept migrants and refugees departing from Libya and pull them back to shore, where they face well documented grave human rights violations including torture and abuse.

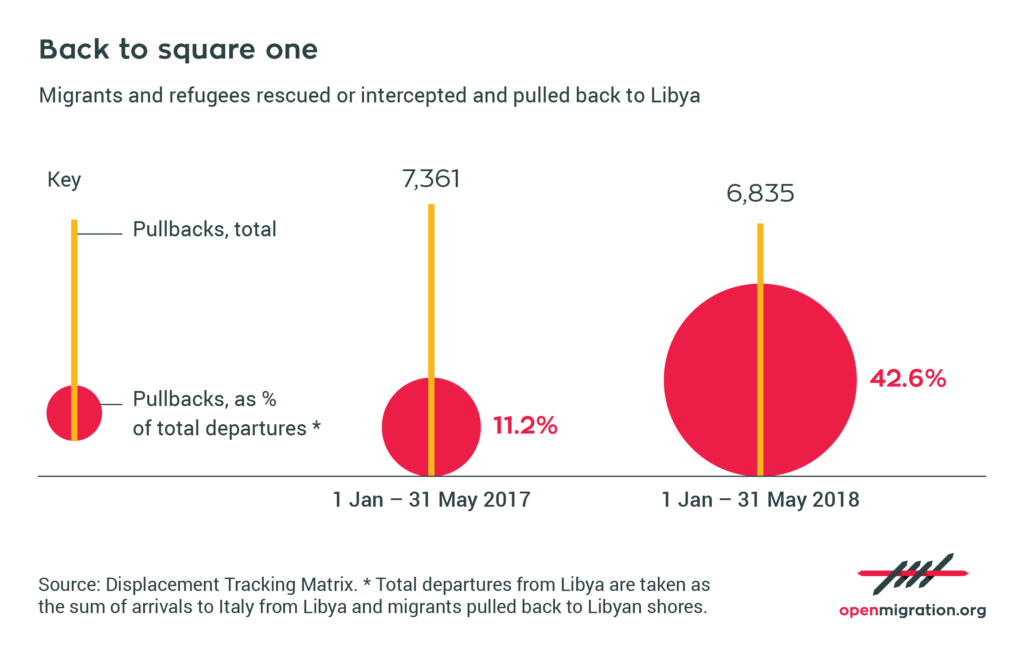

The International Organisation for Migration in Libya has told us that between 1 January and 31 May this year, 6,835 migrants and refugees were rescued or intercepted in maritime incidents and returned to shore. The figures are based on updates from the Libyan Coast Guard, Libyan Coast Security, Libyan Red Crescent and other local organisations and, as of the start of this year, are published as monthly updates on the UN migration agency’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM).

IOM Libya also told us that as of 13 June 2018, 7,114 migrants and refugees had been rescued or intercepted and pulled back to Libya.

In absolute terms, these figures are lower than last year, when in the first five months 7,361 individuals were returned to Libyan shores. At year’s end the number stood at 18,900. These numbers are slightly diverging from the incomplete ones published on the Displacement Tracking Matrix and they were also provided to us by IOM Libya.

However, if taken as a percentage of total departures from Libya – taken as the sum of arrivals to Italy from Libya and migrants pulled back to Libyan shores – the picture looks very different.

As of 31 May 2018, 42.6 per cent of migrants and refugees who departed from Libya and lived to tell the tale ended up back where they started. This is a significant increase with respect to the same period in 2017, when the proportion was 11.2 per cent.

Then there are the migrants and refugees who have lost their lives at sea, including within the context of the activities of the Libyan coast guard.

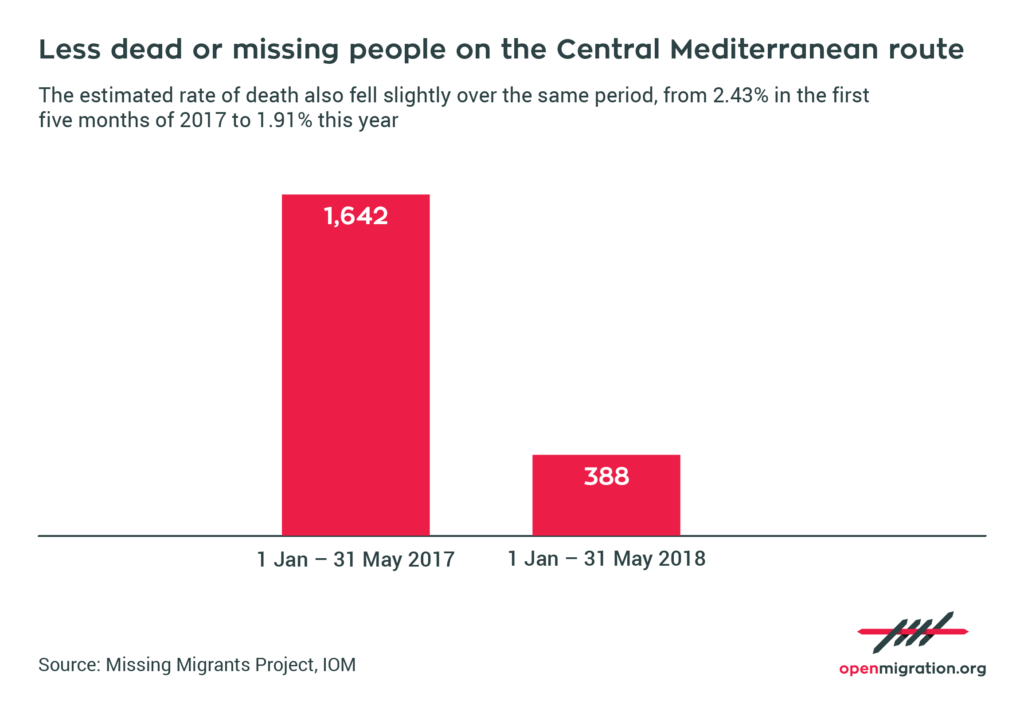

In absolute terms the number of migrants reported to have died or gone missing on the perilous Central Mediterranean route is coming down. As of 31 May, 388 people were reported dead or missing since the start of the year, a 76.4 per cent reduction with respect to the 1,642 recorded in the same period in 2017 according to IOM’s Missing Migrants Project, which compiles its data from IOM, national authorities and media sources. This is in line with the drop in arrivals to Italy.

The estimated rate of death also fell slightly over the same period, from 2.43 per cent in the first five months of 2017 to 1.91 per cent this year. These data include both arrivals to Italy and migrants returned to Libya.

However, first semester data could look different, as there have been a number of deadly maritime incidents in the Central Mediterranean region already in June.

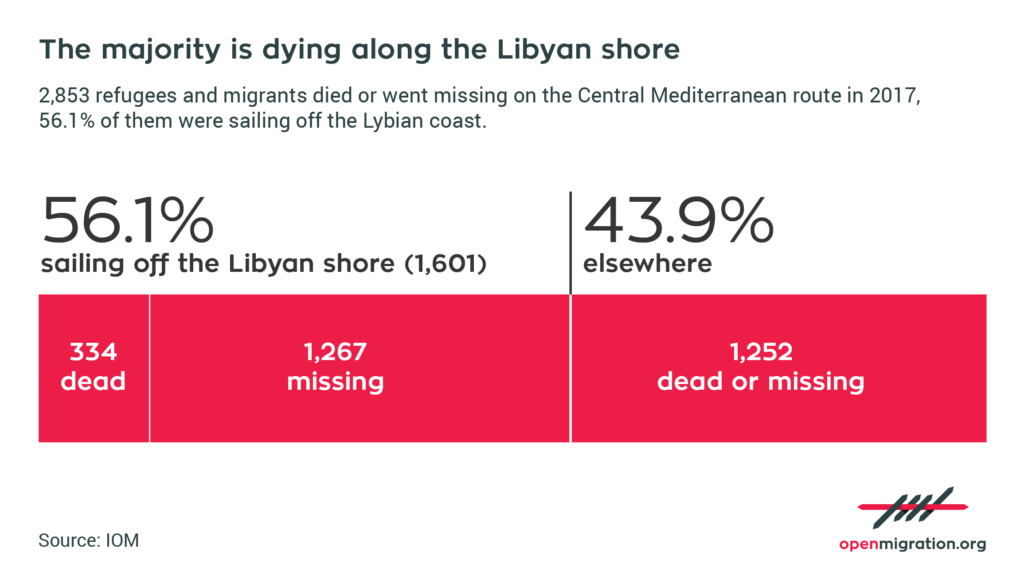

IOM Libya has told us that in 2017, 334 deaths were recorded along the Libyan shore and an additional 1,267 migrants were reported missing. This represents 56.1 per cent of the total of 2,853 reported deaths and disappearances on the Central Mediterranean route last year. Further, IOM Libya’s Christine Petré says that “the actual figure is likely much higher”.

In early May, Global Legal Action Network (GLAN) and the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI), with support from the Italian non-profit ARCI and Yale Law School’s Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic, filed a submission against Italy with the European Court of Human Rights in relation to a confrontational rescue operation on 6 November 2017 involving a migrant rescue boat operated by German NGO Sea Watch and a Libyan coast guard patrol vessel operating under the coordination of the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) of the Italian Coast Guard in Rome, in which as many as 34 people including two children are thought to have died.

Of the approximately 140 migrants on board the dinghy in distress, 59 were rescued by Sea Watch and taken to safety in Italy and 47 were returned by the coast guard to Libya. There, several faced serious human rights violations including detention, beating, rape and torture to extract ransom from their families.

The application – made on behalf of two survivors who were pulled back to Libya and 15 who were instead taken to Italy – raised complaints under Article 2 (right to life) and Article 3 (prohibition of torture and inhumane or degrading treatment) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and Article 4 of Protocol 4 (prohibition of collective expulsions) and made use of evidence compiled by Forensic Oceanography based at Goldsmiths, University of London.

This is not the first case of its kind brought against Italy over interception-at-sea: in 2012, in the so-called Hirsi case, the country was found guilty of violating Article 3 EHCR and Article 4 of Protocol 4 in relation to an incident on 6 May 2009, when three boats carrying approximately 200 migrants were intercepted by the Italian police and coastguard in the Maltese Search and Rescue region of responsibility on their way from Libya to Italy, transferred onto Italian military vessels and handed over to Libyan authorities in the port of Tripoli.

The difference now is that Italy allegedly acted indirectly through the Libyan coast guard, operating the push back by proxy and in violation of the principle of non-refoulement, whereby countries receiving asylum seekers are forbidden from returning them against their will to a territory where their life or freedom could be at risk.

In its report Mare Clausum, Forensic Oceanography says the 6 November 2017 incident is “paradigmatic of the new drastic measures that have been implemented by Italy and the EU to stem migration across the central Mediterranean”.

“This multilevel policy of containment operates according to a two-pronged strategy which aims, on the one hand, to legitimise, criminalise and ultimately oust rescue NGOs from the central Mediterranean; on the other, to provide material, technical and political support to the LYCC so as to enable them to intercept and pull back migrants to Libya more effectively, it continued.

If the figures on maritime incidents in Libya are anything to go by, the strategy is certainly working. And it is no accident that in one of his first statements as Minister for the Interior, Matteo Salvini praised his predecessor Marco Minniti and said “nothing of what has been done that is positive will be dismantled”.

“I will work to make the policies of control, pushbacks and expulsion even more effective,” added Salvini, who is also deputy premier and leader of the xenophobic and Eurosceptic League, on 4 June.

The government is “working” to provide additional patrol vessels to the Libyan coast guard, according to Minister for infrastructure Danilo Toninelli. And Salvini went to Libya on a official visit – so far with no results after his talks with the Serraj government.

Cover photo: A Libyan Coast Guard unit photographed from ProActiva Open Arms’ Golfo Azzurro vessel on August 15, 2017