“Our wiretapping services recorded specific conversations in which the defendant was planning to interrupt his criminal activities for some months and, in particular, to leave Libya in order to most likely head for Sweden, where his wife, Tesfu Lidya, who was pregnant at the time, lives.”

This is an excerpt from the bill of indictment of July 4, 2016, with which the public prosecutors Calogero “Gery” Ferrara and Claudio Camilleri requested (and obtained) the committal for the trial of 14 people. Among them are Abdul Razak, Ermias Ghermay, Wedi Issack, and, most interestingly, Medhanie Yehdego Mered. These are the four human smugglers who, from 2013 on, have sent numerous migrants to their deaths in the Mediterranean, including the 368 people drowned or still missing from the infamous Lampedusa tragedy of October 3, 2013.

The defendant Ferrara and Camilleri are referring to in the excerpt is Mered, nicknamed the General, the smuggler they are convinced they arrested on June 8, 2016. But, as we have already explained, there is a fair amount of evidence suggesting that they may have put the wrong man in jail.

Indeed, there is so much evidence that, until now, trial proceedings have focused only on the identification of the accused, although almost two years have passed since his arrest. The only absolute certainty is that the man in prison is named Medhanie Tesfamariam Berhe and is the son of a 59-year-old woman, Meaza Zerai Weldai. According to the prosecutors, this is simply an alias for the smuggler Mered, but defence lawyer Michele Calantropo maintains this is the only identity of the defendant, who claims to be a carpenter.

The DNA test on Raei Yehdego Mered

The last piece of evidence that Calantropo produced in order to defend his client was the DNA test of the baby Lidya Tesfu had been expecting. The child’s name is Raei Yehdego Mered, and he is presumably the son of the smuggler Medhanie Yehdego Mered.

At the end of March, Calantropo flew to Sweden with his consultant Gregorio Seidita, an expert in genetics from the University of Palermo. They went to Eskilstuna, 120 kilometres from Stockholm, a town of 70,000 inhabitants with a large Eritrean community and the headquarters of one of the most important associations of the Eritrean diaspora. But first and foremost, it is the place where Mered’s wife and son live. “For two years I had been waiting for Lidya Tesfu to consent to a DNA test on herself and her child. She had always been doubtful, and so we had to leave immediately,” the lawyer explains. The DNA test was based on a comparison between the data obtained from the child’s and the mother’s saliva and those of the man in jail.

The result, according to the defence expert’s report, categorically excludes any father-son relationship between the detainee and the child. “If I had waited for the Court of Assizes to finance my trip, as free legal aid, I would have risked losing this chance, but this was too important,” Calantropo adds.

Mered’s partners on social networks

Two days after being taken to Pagliarelli prison in Palermo, during his first interrogation in Italy, Medhanie Tesfamariam Berhe, the man public prosecutors believe is the General, declared he did not know Lidya Tesfu. He has never had any wife or son; during the hearing of March 19 this was also confirmed by Berhe’s sister, Hiwet Tesfamariam Berhe. The siblings were born of the same father, although, as frequently happens in extended Eritrean families, they have different mothers. Nevertheless, they all lived together as one family.

Lidya Tesfu is a girl from Asmara, she was born in 1993 and gave birth to her son in 2014. She is 12 years younger than Medhanie Yehdego Mered. A photo on her Facebook page shows her next to her husband, both in their Sunday best, and the age gap is evident. Lidya is dressed in a bright, skin-tight purple dress and is looking down at the ground. At her side Medhanie Yehdego shows off a large tie the same shade of green as his waistcoat. There isn’t any other picture of them together on any social networks. And yet the conversations recorded by investigators reveal such a strong bond between the two that Mered may have actually considered stopping his smuggling activities, at least for a period of time, to go to Sweden to see his child for the first time.

The photo was posted on Facebook on December 20, 2014, as a comment to another picture with two cups, and featured Lidya Tesfu’s dedication: “For my beloved”. Another significant image, expressly dedicated to her husband, shows two lovers kissing, with the comment: “Ahahaha, this is for Meda.” All of these pictures were uploaded over a 48-hour span.

But little Raei may not be the General’s only child. Between March 20 and 25, 2013, Lidya Tesfu shared the picture of a baby girl taken from the page of another young Eritrean, Semhar Yeman, born in 1989. This woman could be the same Semhar that public prosecutors mentioned as the partner of a certain Medhane in the warrant issued on May 11 by the judge for preliminary investigation of Palermo. On that occasion, “Medhane” was not clearly identified, but as far as general opinion was concerned he was the same Medhanie Yehdego Mered involved in this trial.

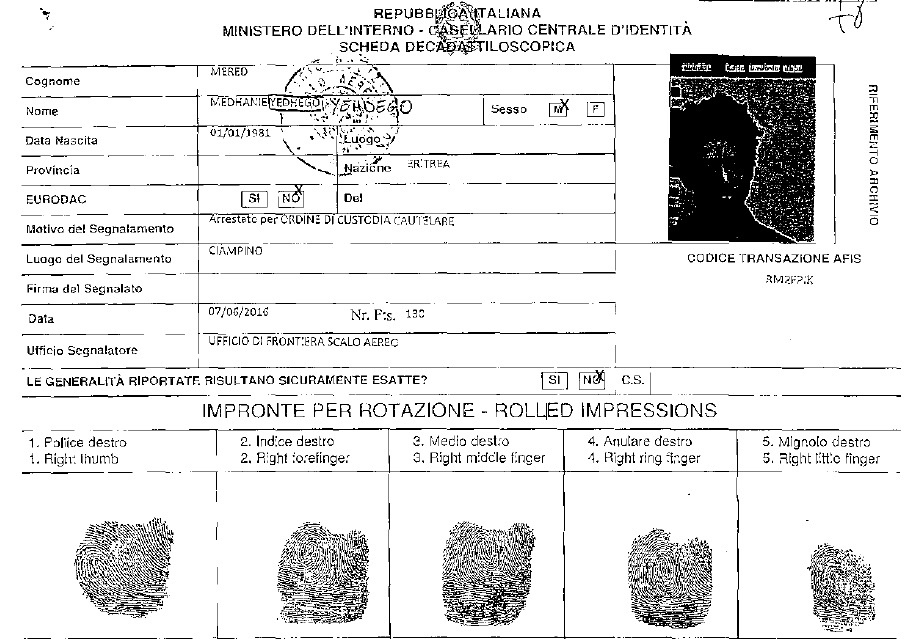

Le impronte digitali registrate per Medhanie Mered

In the prosecutors’ opinion, Semhar Yeman had a child with Mered, too. In July 2014 she posted a picture of her baby riding a motorbike; the same picture appeared four days later on the Facebook profile meda.yedhego, which has been said to belong to the smuggler Mered. The hypothesis is that the child could be his and Semahr’s, and that Lidya Tesfu shared it on her page for being a part of her own family.

One last link between Semhar and Mered was found in a wiretapped conversation dating back to June 2014 and included in the above-mentioned warrant. In the transcription Mered bragged about smuggling more than 1,400 people to Italy over the previous week. As the dialogue reveals, Semhar and her daughter were also supposed to go to Italy later on. No one knows where the girl, who last updated her page in 2016, currently lives. The only available information is that, when the conversation was wiretapped, she was in Israel with her baby.

Meron Estefanos’s doubts

“There should be two separate trials; one to identify Mered’s responsibilities, and the other to ascertain the identity of the detainee. But everything has been kept together. This trial is absurd,” says Meron Estefanos, an Eritrean activist and journalist living in Sweden. She was contacted by Medhanie Yehdego Mered himself in February 2015, and heard as a witness on January 22 of this year. During her radio broadcast in Sweden – which is quite popular among Eritreans of the diaspora – Estefanos had given space to the testimonies of many families reporting the tortures and rapes suffered by their loved ones at the hands of Mered, who at that time was smuggling human beings in Israel. Mered contacted Estefanos and asked for an interview so he could reply to such allegations. That phone call was followed by more; during one of them the trafficker told the journalist – she wanted to meet with him for a documentary – that he was about to leave Libya for Sudan. The call took place between June 8 and June 10, 2015.

While conducting her research, Estefanos got in touch with Mered (although never face to face) and denounced his trafficking. Because of her job, she also met the other smuggling “leaders” who had been identified in the Glauco investigation in Palermo. “I don’t understand why the trial links Mered to the shipwreck in Lampedusa. Ermias Ghermay was the owner of that boat, not Mered,” she points out.

The starting point of the prosecution’s entire case is the shipwreck of October 3, 2013: the main goal of the Glauco investigation – later turned into Glauco I, II, and III – is to identify the culprits. The bill of indictment that led to the committals for trial for the second and third phase reads: “As investigations have proven, the criminal partnership led by ERMIAS [Ghermay] and MERED Medhanie Yehdego in Northern Africa” was at the centre of “criminal activities” at least until 2015.

In light of her knowledge of this phenomenon, Estefanos’ reports have been used by several European law enforcement bodies, especially in Sweden and the Netherlands, countries that have been cooperating with Italy on this investigation. During her testimony in January, however, prosecutor Gery Ferrara questioned Estefanos’ credibility, alleging that the timeline of her phone calls with Mered showed some inconsistencies. In the meantime, Estefanos has continued to work, and she recently cooperated with the Swedish public television broadcaster SVT to track down the smuggler. Investigations have led her and her colleague Ali Fegan to Uganda, where some sources indicate the Molober bar in Kampala as one of Mered’s haunts. But it is highly probable he has already escaped somewhere else, thanks to the increased attention on the African country.

Ugandan authorities have not investigated Mered’s stay in the country yet, pending an official Italian request. Nevertheless, the local newspaper Observer reported that, while in Uganda, Mered allegedly purchased a new passport in the name of Habte Amanuel with the help of a bribe and some acquaintances in the local visa office.

The Swedish broadcaster also confirmed its possession of another file in which a European police authority states that they are ready to detain the real smuggler. They only need a new arrest warrant from the Italian prosecutor, who so far has remained silent (this story was also covered by The Guardian).

The unheard plea of the Eritrean community

In January 2018 Elsa Chyrum, a political dissident from Eritrea who has been living in Great Britain for over 20 years and who founded the association Human Rights Concern-Eritrea, wrote an open letter to Ministers Minniti and Orlando to plead for the release of Medhanie Tesfamariam Berhe, who she believes is innocent. Considering the judicial quagmire, she tried to pressure various institutions, all to no avail. “We never received a reply,” she told us in a letter in February.

“No one can be one hundred per cent sure why Berhe is still in jail; however, his arrest and detention clearly represent a colossal failure and an international embarrassment for the authorities involved,” she continues.

In fact, it is important to remember that the consequences of Mered’s trial reach far beyond the walls of Palermo’s courthouse. The Glauco investigation has received significant support from Sophia – the operation conducted by European navies to stop smugglers – and has seen the cooperation of Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Its failure would jeopardise the European anti-smuggling system as a whole.

For now, the only consequence of Operation Sophia for the leaders of the smuggling chain operating in Libya is the detention of the alleged Mered, which the Italian Interior Minister referred to as “the arrest of the year”. The mission has been renewed until the end of 2018, but its scope is expanding: on May 14 the European Commission decided it would now “be tasked with facilitating the receipt, collection, and transmission of information on the implementation of the UN arms embargo on Libya” and “conducting surveillance activities and gathering information on the illegal trafficking of oil exports.” Such reformulations of the mandate pave the way for a revision of the mission itself. In light of its poor results in the fight against human smuggling and the little attention paid towards the trafficking of crude oil and diesel, it is better to turn Sophia in a new direction so that it can intercept ships at sea, regardless of the illegal activities they may be suspected of. Sophia’s contribution to Mered’s case was mainly on land, with an intelligence operation focusing on the smuggler’s network. The results are there for all to see. Working at sea allows for easier and better results, at least in figures: thanks to Operation Sophia, 145 smugglers have been arrested, most of whom are still awaiting trial to determine their criminal liability.

Cover image: Lidya Tesfu with her husband, trafficker Mered. This photo was posted on Facebook on December 20, 2014.