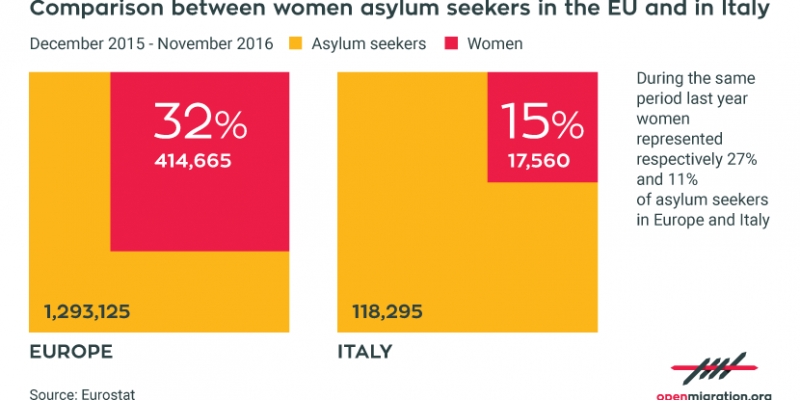

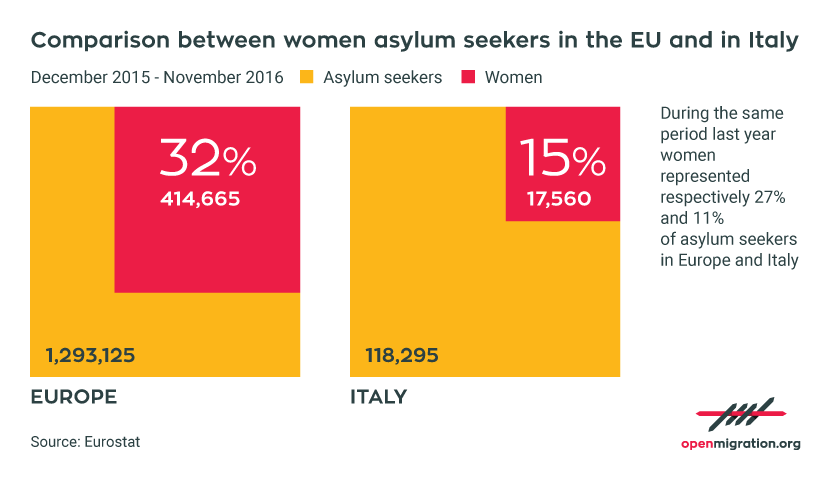

We resume our analysis of migration flows where we left off a year ago: according to Eurostat data, between December 2015 and November 2016 there were 1,293,125 asylum seekers in the European Union, 414,665 of whom were women (32 per cent). A marked increase from the same period the previous year, when women made up 27 per cent of asylum seekers.

As for Italy, there were 118,295 asylum seekers in the same time frame, 17,560 of whom were women; the percentage of female asylum seekers has gone up from 11 to 14.84 per cent. Their number, however, almost doubled (+86 per cent) from 2015, when there were 9,435 women seeking asylum.

Comparing Italy and the EU, we found that 9.15 per cent of asylum seekers in the EU applied for asylum in our country (compared to 6.7 per cent last year) and that the same percentage among women was 4.23 – that is, 2.8 percent more than last year.

It must be noted that these numbers do not represent the entirety of the direct migratory phenomenon to Italy. In 2016, 181,436 migrants arrived by sea (source: UNHCR), 13 per cent of whom were women; in other words, roughly the same percentage of women requesting asylum here (14.84).

Countries of origin: 40 per cent of women come from Nigeria

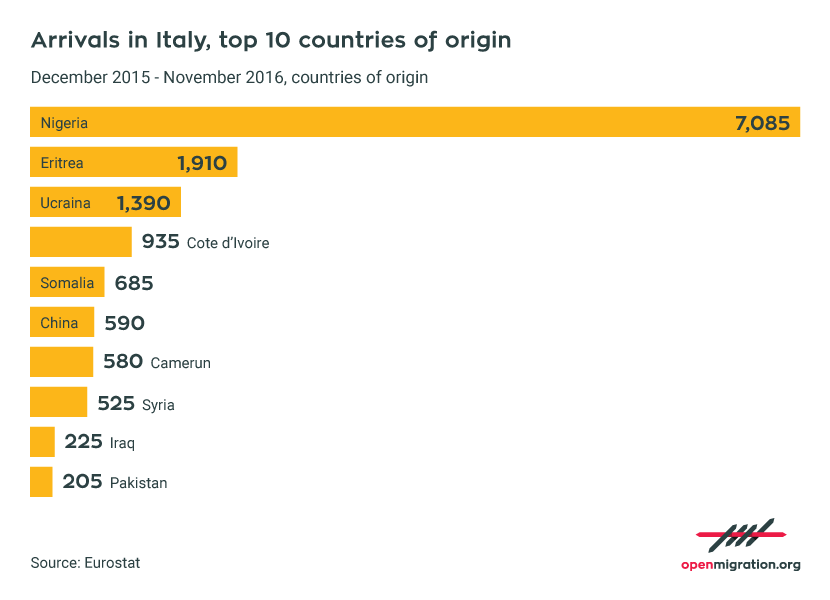

Of the total number of migrant women, as well as among female asylum seekers, Nigerians are the most numerous group. More than 40 per cent of women requesting asylum (7,085) are from Nigeria, followed by Eritrea (1,910, or 10.9 per cent) and Ukraine (1,390, or 7.9 per cent). Eritrea and Nigeria are also the most represented countries as to the total number of arrivals by sea (20.7 and 11.5 per cent respectively).

As noted by the UNHCR as well as the latest report from GRETA (Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings), the amount of Nigerian women and girls arriving in Italy and seeking international protection has grown over the last number of years. In particular, the number of women arriving from Nigeria has nearly doubled (+95.5 per cent): from 5,633 in 2015 to 11,009 in 2016. Italy, after all, is the principal destination for migrants fleeing Abuja. Women, on the other hand, often end up being exploited and forced into prostitution.

Women on the move: the decision to leave

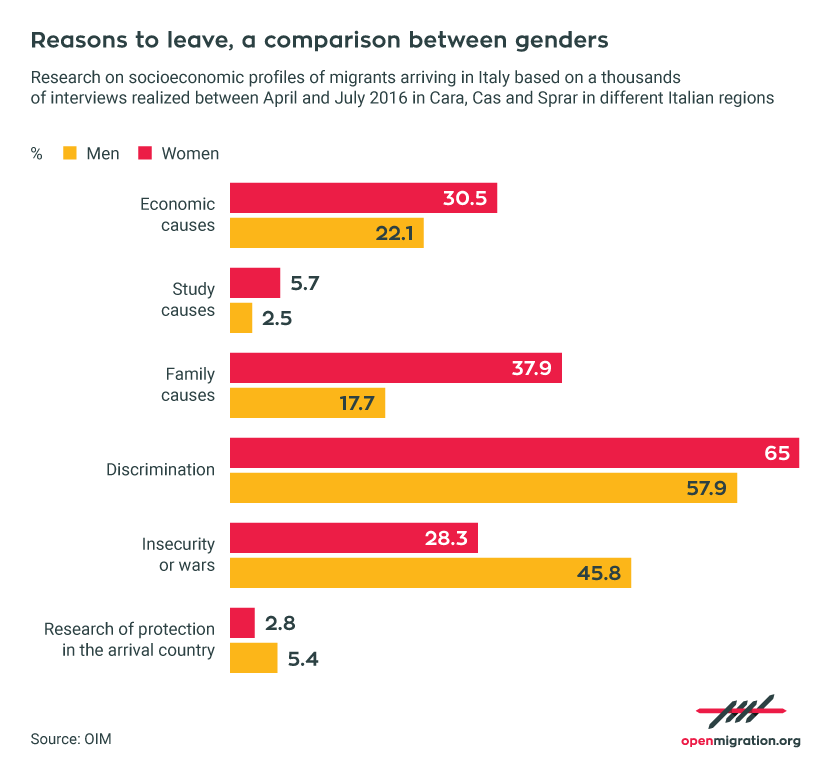

According to an IOM report – A study on the socioeconomic profile of migrants arriving in Italy based on interviews conducted between April and July 2016 with a thousand migrants at open reception centres (CARA), temporary reception centres (CAS) and secondary reception centres (SPRAR) in several regions of Italy – the reasons which drive migrants to leave change dramatically according to gender “There is a striking difference in the percentage of women versus men that left for family or friend-related reasons (37.8% versus 17.8%),” the report reads. “Many women, in fact, report leaving to avoid abuse within the family, forced marriage or to follow a partner.” Discrimination, on the other hand, is less frequent. The driving factors for men leaving also include affiliation to political or religious groups, which play a smaller role in women’s decision to leave.

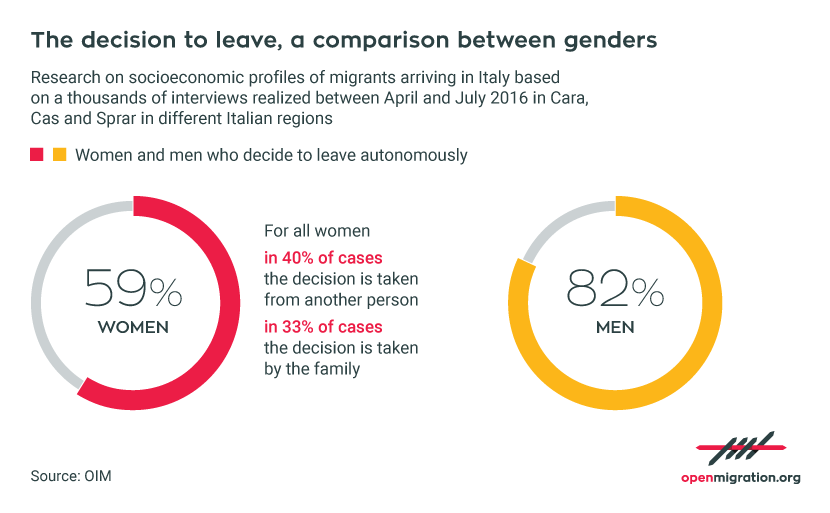

The same report underlines another interesting fact. 82 per cent of male migrants made the decision to leave primarily on their own, versus 59 per cent of women. This means that, in 2 cases out of 5, the decision is made by somebody else. In one out of 3 cases, the family decides, either because the woman follows her partner or because she precedes him, seeking protection so that the family can then ask to be reunited. In some cases, women are sold into sexual exploitation.

What happens during the journey: from violence to human trafficking and forced prostitution

According to the GRETA report, 70 per cent of children and women from Nigeria display signs of having been the victims of human trafficking for the purpose of work and sexual exploitation. The IOM even estimated that 80 per cent of Nigerian women arriving in Sicily in 2016 were victims of trafficking, and destined for the prostitution market in Italy.

Uncertainty about the exact figures stems from the difficulty of identifying the victims, who cannot – or will not – tell their stories. This is why, in order to recognise victims, operators rely not only on verbal accounts, but also on clues, indicators such as those listed by the IOM in its report on the victims of human trafficking who landed in Italy in 2014-15; these range from personal information (nationality, geographical region of origin, age, educational and family background) to behaviour upon arrival.

Even when the migrant has not been a victim of trafficking, she is very likely to have suffered violence throughout the journey, either at the hands of those in charge of transfers or those who manage the camps.

- According to a European Parliament (Policy Department Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs) report on the reception of female refugees and asylum seekers in the EU, women travelling alone may be subjected to sexual and gender-based violence, both during the journey and inside reception centres. Some women even marry someone on the journey out of desperation for protection.

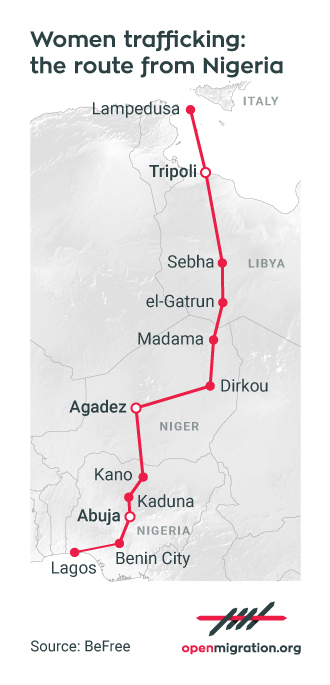

- According to “Inter/rotte – Storie di tratta, percorsi di resistenza”, a report published in April 2016 by the association BeFree and based on interviews conducted with 100 Nigerian woman detained in the Ponte Galeria CIE, violence and exploitation were commonplace while crossing Niger and in Libya, where the women were detained before sailing to Italy. Nigerian women passing through Niger “are brought to Agadez, in connection houses where they are often exposed to violence and forced into prostitution in order to continue their journey,” the report reads. “In Niger, voluntary migrants and victims of trafficking alike are made vulnerable by depriving them of money, personal belongings, information and contact with the outside world, and in the process they become bound to organisations which, in the early stages of the journey, appear to grant them more freedom […] Nigerian women forced into prostitution are the weakest link in an extended chain of people deprived of identity.”

- Violence during the journey, particularly in Libya, through which 89.7 per cent of the migrants coming to Italy have to pass, has also been documented by Amnesty International: women are often gang raped by their traffickers with no regard for their nationality or age, or even if they are pregnant. “People sell people. Selling people is normal in Libya. […] Everybody has a gun in Libya.” This is the chilling tale Maria (her name has been changed), aged 26, from Cameroon, told the MSF operators who rescued her. She is not, however, the only woman with a similar story: those who find the courage to speak have told tales of mass rape, girls abused by intoxicated traffickers, mothers raped in front of their children. Rape is used as punishment if the girl does not have the money to pay for her journey, or to force her family to send a sort of “ransom”. To avoid unwanted pregnancies that could become further obstacles to the journey, women start taking massive doses of contraceptives months before leaving, with serious consequences to their health, as medical operators have found upon examination at reception centres.

Victims do not report their exploiters

One would think that, upon arrival, things would get better, but that is not always the case. Recognising victims of violence, let alone those of human trafficking, is very hard, both for practical and procedural reasons (read more in the following paragraphs), as well as for the women’s general reticence to relate their experiences. There are multiple reasons for this state of affairs:

- Lured by the promise of regular employment (such as babysitting or domestic help), victims of human trafficking do not reveal details about the exploitation networks that brought them to Italy to operators for fear of losing those promised jobs. The fragmentation of the control chain, due to the women being sold to different individuals while crossing countries, prevents the victims from connecting their exploiters to the maman who ultimately paid for their trip to Italy. It is what BeFree calls “making the victim loyal to the organisation.”

- According to a report on protection risks for women and girls in the refugee and migrant crisis by the UNHCR and Women’s Refugee Commission, victims of trafficking do not speak about their experiences and do not seek specific assistance unless they have serious health issues. This is partly due to shame for the violence they suffered, but not only.

- Before leaving, some women undergo voodoo rituals involving hair locks, fingernails and spells, which bound them to their tormentors. “Most of them, as soon as they set foot on land, immediately change their attitude: they keep their gaze low, stop answering any questions and act terrified; they know someone is waiting for them and that if they don’t obey orders, the voodoo rituals they went through before leaving will bring evil to their families,” an obstetrician with Doctors Without Borders explained to a reporter from La Repubblica.

This is why it’s difficult to recognise victims of trafficking and why, rather than only paying attention to their reports, detection should be based on the indicators set by the IOM, including signs of physical abuse, psychological problems, obvious forms of control in reception centres. This requires personnel trained in helping victims of violence, translators and cultural mediators. In short, it requires time.

What happens when they arrive in Italy

According to the GRETA report, the Territorial Commissions for Recognitions of International Protection has received instructions on identifying victims of trafficking among applicants for international protection. Interviews are to be carried out in a gender-sensitive manner, with the interviewer and the interpreter being of the same gender as the applicant. Indicators to detect possible victims must be used, also by collaborating with specialised NGOs or the IOM when needed.

The migrants, however, may never get to apply for asylum because of the pre-identification phase that is performed immediately upon arrival during which migrants are asked questions about the reason for arriving in Italy in an irregular manner, and are presented with specific options: “to seek work, “to escape poverty”, “to seek asylum” or “to reunite with family”. This process, though, is so quick that potential victims, who are often unaware of their status, can easily give the wrong answers; citing economic reasons, for example, they will receive an immediate expulsion order. And this is precisely what happened in September 2015 when about 20 (initially 66, according to other reports) Nigerian women were forcibly returned to Nigeria despite displaying signs of being victims of human trafficking.

According to the GRETA report, based on observations conducted in Pozzallo, the role of police officers working in the hotspots is focused on registration and fingerprinting, and there is no time for detecting possible victims of trafficking. Furthermore, victims may only be willing to speak after several weeks.

In Italian hotspots, IOM has staff trained to identify potential victims of trafficking. Thanks to this, IOM found 75 women who were abused in 2015, and 184 in the first five months of 2016. However, many of the people interviewed by IOM are not formally identified as victims of trafficking because the requirements for granting a residence permit – that is, “concrete risk” and “gravity and imminence of the danger” – cannot be proven. This situation exposes the women to further exploitation, whether in Italy or in their countries of origin, following repatriation. Furthermore, GRETA has pointed out, hotspots lack private spaces to conduct such delicate interviews and, after just a few days in the hotspots, more than a few women have disappeared overnight, once again at the hands of forced prostitution networks.

When they are repatriated, these women are exposed to the very same conditions that they fled, the same profiteers who brought them to Italy in the first place, the same acts of violence. As vulnerable individuals, they should have the right, if not to protection, than at least to assistance upon return to their countries of origin by being enrolled in the assisted repatriation programmes which exist for this very purpose. If these obligations (provided for by the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings) cannot be met, GRETA concludes, carrying out forced transfers is in direct violation of the principle of non-refoulement.

Another dangerous proposition is preventing migrants from leaving Libya, effectively confining them into a no man’s land where they are exposed to all kinds of abuse. The recently signed agreement with the Italian government has already drawn protests from humanitarian organisations such as Caritas and Migrantes, which are once again campaigning for safe and legal access routes to Italy.

The management of migration phenomena cannot be resolved by calculations, with the risk of becoming complicit with human trafficking. Therefore, the need for prompt identification of migrants upon arrival in Italy does not justify a hurried sorting of people. To repatriate a migrant, without knowing her history and without providing any form of assistance, could mean sending her back into the hands of her tormentors. This is all the more true for vulnerable individuals, women and minors, whose already difficult journey is made even more perilous by many additional dangers and risks.

Translation by Francesco Graziosi. Proofreading by Alex Booth.